Suddenly, everyone’s wearing paracords and Gramicci.

Indoor rock climbing has gripped the nation. In the last few years, at least six new bouldering gyms have cropped up across Metro Manila, Cebu, Iloilo, and Davao City. Long queues and waitlists to bouldering gyms are regular programming over the weekend. You run into someone at the mall with rock shoes and Labubus carabinered to their The North Face Fuseboxes.

It seems like climbing has become the cool new thing again in the Philippines.

The sport peaked around the late ‘90s when competitions were regular, four-leg events joined by hundreds nationwide. People lost interest around the 2010s when other indoor sports like badminton became more popular, putting climbing gyms at risk of closure.

But now, with climbing in the Olympics, gyms at every corner, and the parkour-like nature of modern bouldering as an addition to one’s Instagram feed, there’s renewed interest in the sport. And it’s creating an interesting shift in local climbing culture.

Deeply rooted in mountaineering, rock climbing gyms were once perceived as a complement to the great outdoors. They were the means, never the goal. But these days, indoor rock climbing has taken a life of its own. There’s a whole new generation of skilled climbers, born and bred in sparkly gyms fitted with state-of-the-art hydraulic system boards and co-working spaces-slash cafes. Some climbers who have been doing the sport for years may have never heard of legendary American climber Chris Sharma, who developed many crags and iconic first ascents, or scaled real rock before.

[C]limbing is still closed within the community in the Philippines. If you don’t make an effort, you won’t be able to climb outdoors.

Of course, that isn’t for a lack of wanting. Many who have plateaued at the gym want to test their skills in a different context — but the question always is: How to start?

With the sport’s comeback in the country and gyms becoming the new entryway for people to discover the outdoors, it has revived discussions repeatedly opened and shut: creating an outdoor rock climbing guidebook.

Aye, there’s the crux

When Christoph Bastin, the man behind The Bouldering Hive (Bhive), hosted an event in partnership with the outdoor climbing initiative Bolt Fund, he invited the top patrons of his gym to boulder in the river crag of Ambongdolan, Baguio. For many, it was their first time climbing outdoors. And after the event, certainly not the last.

During the trip, climbers experienced the thrill of grasping nature-made holds. They camped, trekked, and brewed each other coffee on butane stoves. It was also during this trip when they met many of the mainstays of the outdoor climbing community — people like Rhei Salvilla of Baguio or Abon Ramos of Albay, Bicol. Once they got in contact with these people, Bhive climbers started organizing outdoor rock trips of their own.

“The number one resource regarding outdoor climbing or outdoor areas is really the gym or the people you meet in the gym who climb outdoors,” said Carlos Makinano Jr., fondly referred to within the community as Kuya Mackie.

“Unlike in the United States or Europe where climbing is always featured on TV or in magazines, and information about climbing [spreads] faster, climbing is still closed within the community in the Philippines. If you don’t make an effort, you won’t be able to climb outdoors.”

Enter: Guidebooks.

Guidebooks are helpful resources for climbers looking to take the sport outdoors. It illustrates the unique features of different crags and how climbers can get there, complete or “send” their projects, and go home in one piece. Guidebooks have the potential to make climbing more accessible for climbers, liberating them from always needing a guide or tapping the same old veterans for information about crags, protocol, and transport.

However, there are only a few published guidebooks in the country. The most recent one still in circulation details the climbing culture, community, and crags of Cebu. Online resources like The Crag offer rudimentary information but are often incomplete, outdated, or sometimes totally wrong.

There have been several attempts by members of the community to create a guidebook and document local climbing history, but these are always foiled by the same culprits.

“If I were to make a guidebook, I’d need to see the area, figure out how to get to the crag,” said Makinano Jr. “I can’t do that without time and money.”

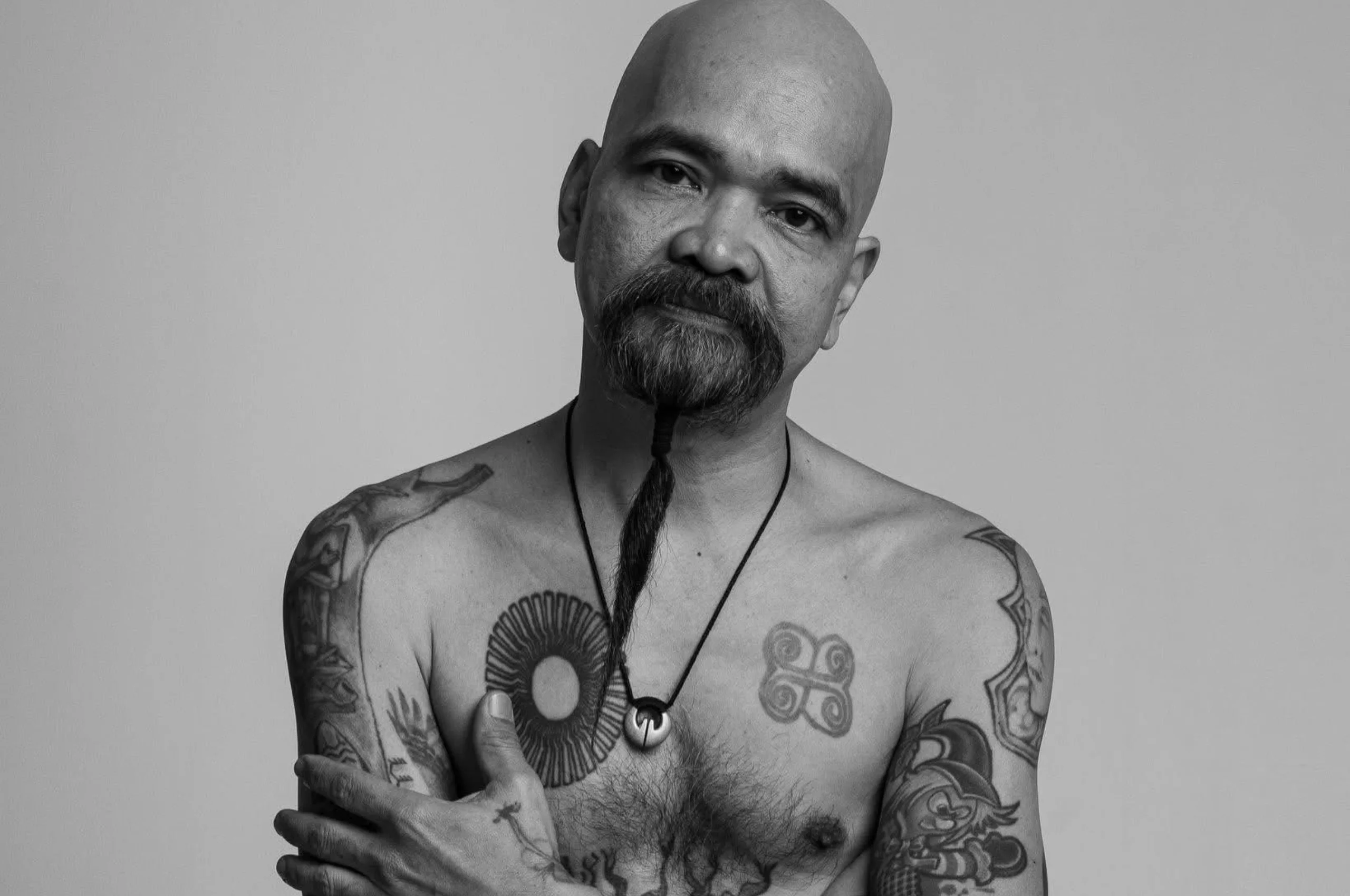

He had a hand in developing nearly every major rock climbing area in the country, from north Luzon to Mindanao. He has bolted over 600 outdoor routes since he started in 1999. And like many outdoor developers, his efforts were largely self-funded, either out of pocket or through the Bolt Fund, his fund-raising initiative

Meanwhile, Cebu-based climber, climbing guide, and author of the Cebu Rock Climbing Guidebook Mervil Patigdas said it took almost a year to develop Cebu’s guidebook. Patigdas and other volunteers in the local community spent months traveling from crag to crag, trying different routes and photographing the process. It was a passion project that he and his team were well-positioned to see through because they were freelancers, working full-time for only a portion of the year. But it was only made possible because it was funded and organized by another local climber, Naoki Ono.

Making a climbing guidebook for the whole of the Philippines — that would be a big task.

“Only a few people make climbing their main livelihood. Some do it on the side, but not their main livelihood … Making a climbing guidebook for the whole of the Philippines — that would be a big task,” Patigdas said.

But now that climbing as a sport is regaining traction in the country, and more boulderers have their noses pointed toward the outdoors, could now be the right time to revisit the conversation?

The case for the guidebook

While developing guidebooks certainly takes investment, there’s a good case for taking the plunge. For one, it’s a good way to showcase the beauty and diversity of the Philippine landscape. Many of these crags are located in small coastal towns that are not typical tourist destinations.

“When barangay officials or local government units find out their area is part of a guidebook, they’re happy. They support it because their area becomes more popular because of climbing,” said Makinano Jr.

Guidebooks also serve as remembrances. They solidify the sport in a country where outdoor climbing is still taking root by chronicling the small rituals that make it special, like paying the fare at Aling Norma’s Eatery in Montalban, Rizal, or cruising down the highway with Manong Bebot in a Budots-blasting trike on the way to Kiokong, Bukidnon.

A unique climbing tradition is how a route is named. The first climber to send a route gets the honor of naming it, so even when the climber passes, the route and its name remain.

“3 Stitches,” for example, is a short, overhung, and burly sport route first ascended by the late Marvin “Gax” Ilanan. It was named such because Simon Sandoval, the first climber to bolt and attempt the route, needed three stitches after slicing his pinky open on a V-shaped crack. Since then, the route has become a test piece in the area with climbers vying to join the few who have sent it.

“I like to explain the story behind a route,” Patigdas said. “Some people complained that there was no information about how steep a route is or what time of day it’s shaded. But for me, the nicest [thing about a route] is its name and the stories behind it.”

Culture, community, and history are what transition routes to test pieces, climbers to legends, and sports to callings. Many of the milestones in Philippine rock climbing today were born out of pocket. What once became a nearly defunct sport was kept alive by the community who continued to tell their stories.

And guidebooks, or books in general, are a way of cementing and passing down experiences unique to the local community — from enduring the horrendous trek up to Uling Wall in Rizal to getting stung by wasps in Igbaras, Iloilo. Many crags and routes become overgrown or inaccessible and are lost to memory over time. But passing down the torch of climbing to a new generation means certain traditions stay alive.

The next big question is: Who’s up for the job?