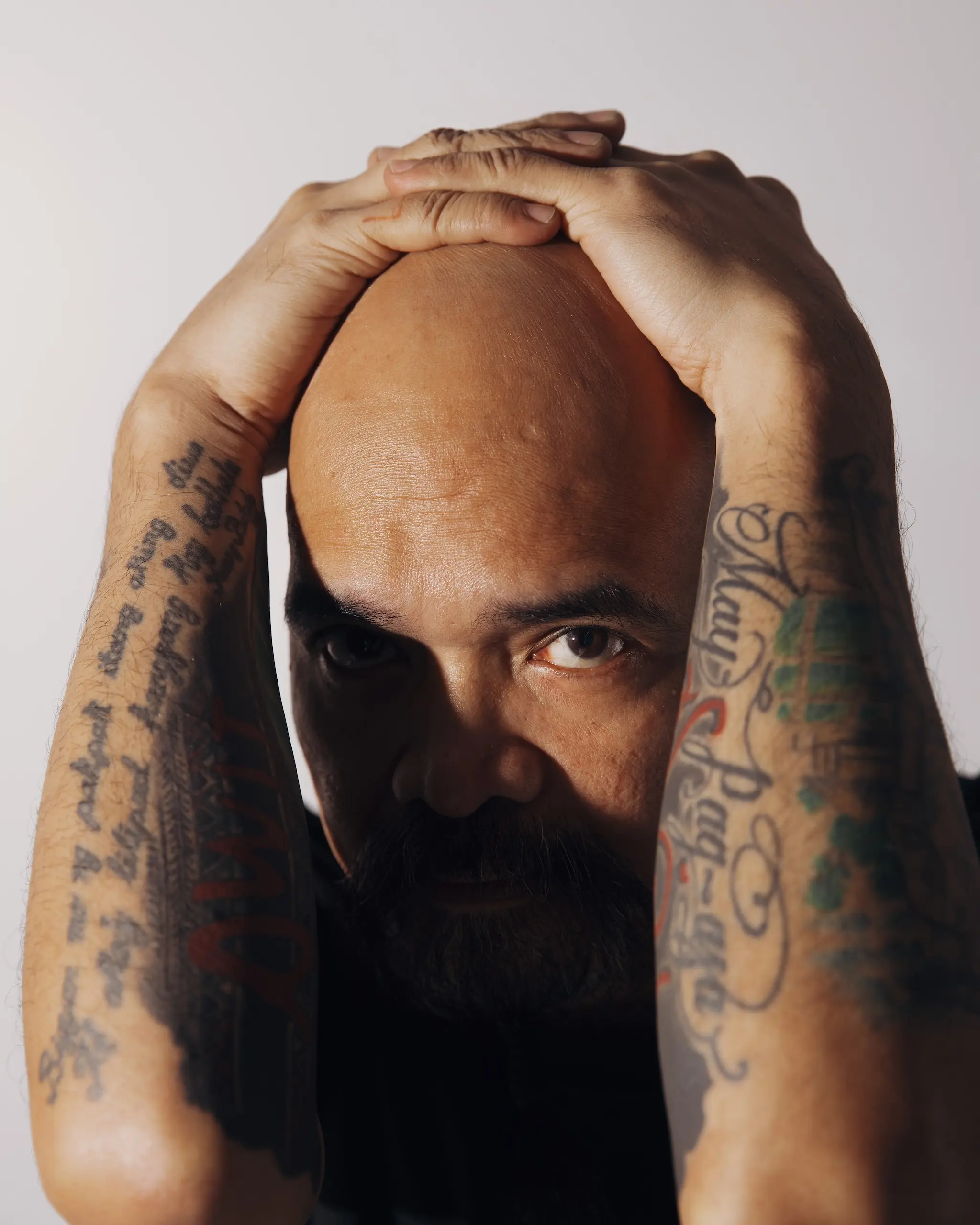

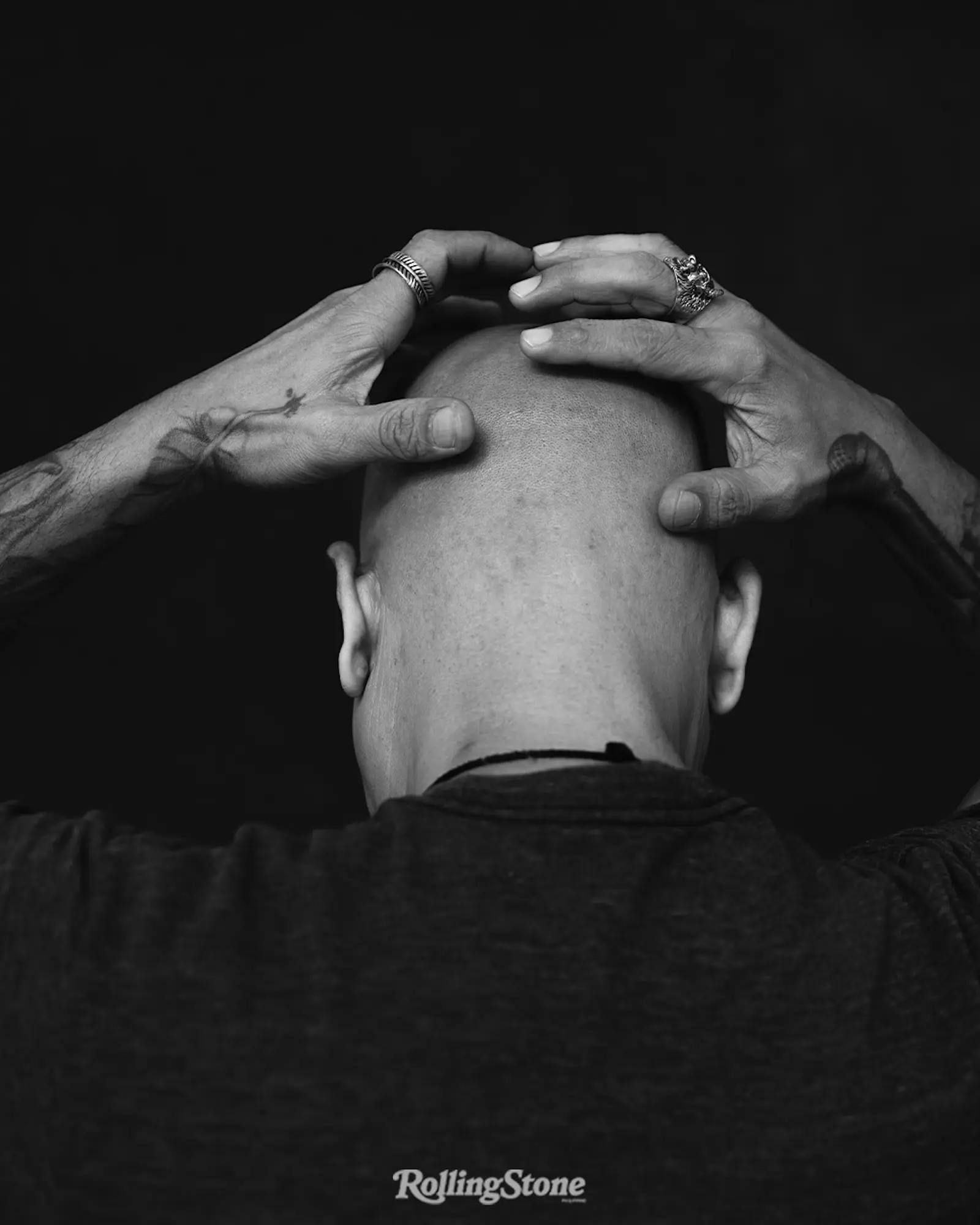

Dong Abay walks into the room — faded Rolling Stones shirt on his back, smile on his face, firm handshake hung suspended — with a purposeful gait, like a man about to put out a fire, or start a religion.

The room is psych ward white and dead silent. It’s the perfect blank slate for the Pinoy punk prophet. His music, after all, doesn’t merely fill space; it body-slams the walls. It doesn’t just crank the volume; it etches its presence into the atmosphere.

“Anong pag-uusapan natin?” he asks. “Pulitika,” I say. He doesn’t flinch. Of course, he doesn’t. He is Dong Abay and flinching isn’t in his vocabulary. Despite this, however, the co-founder of Yano and figurehead of Pan, dongabay, and D.A.M.O. (Dong Abay Music Organization) isn’t too precious about his place under the sun.

While his persona is well-established, he’s more modest about the enterprise, choosing to describe himself as a humble hawker of words. To his mind, although “provocateur extraordinaire” is a shoe that fits, he’d rather wear his trusty tsinelas.

“Kaibigan ko ang salita at ‘yon ang gustong ginagawa ng utak ko most of the time: makipaglaro sa mga salita,” he says. Gone is the angry young man and in his place a wide-eyed force, trading outbursts for answers, fury for focus.

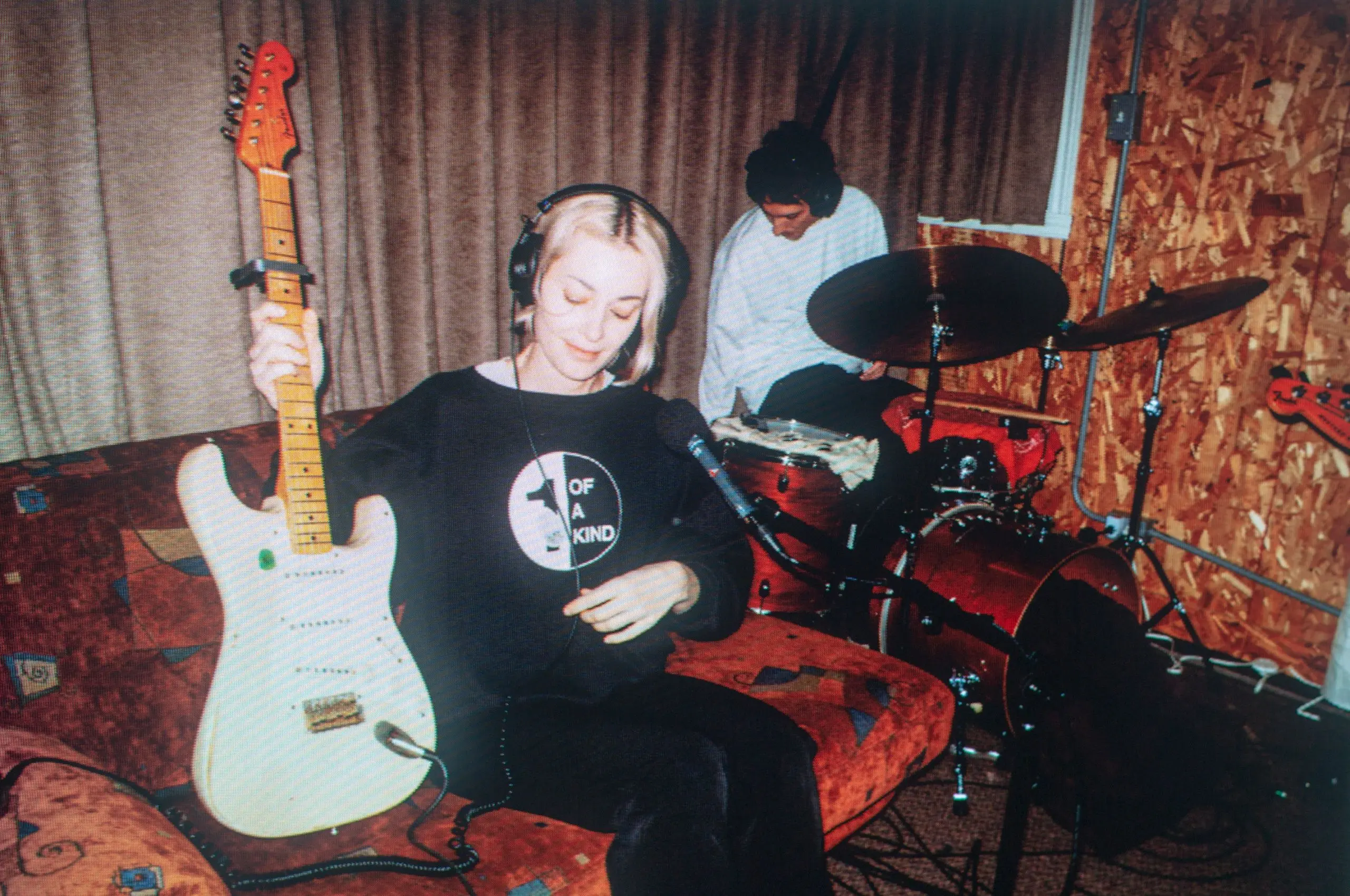

“Disillusioned youth” was the lazy sobriquet pinned onto every flannel-clad kid of the ‘90s. But the Abay of Yano wasn’t writing for kids who lost the dream; he was writing for the kids who never got the memo, who never even knew dreams were on offer. Yano’s self-titled 1994 record, in other words, wasn’t informed by the luxury of misplaced angst; it was framed by the agency-crushing, dignity-erasing, crippling effects of poverty.

Noong nagsisimula ako sa pagbabanda at pagsusulat, [nandiyan] ‘yong mga kwento tungkol sa injustice, sa kahirapan, kwento ng mga ordinaryong Pilipino — hindi maganda ‘yong mga kwento. Tragic.

“Kung tayo lang [ang pag-uusapan], komportable naman tayo e. May aircon, may electric fan, nakakapag-Netflix, alam mo ‘yon?” Abay shakes his head, adding, “Pero paglabas mo ng bahay mo, nandiyan, e. Assault talaga ‘yong lipunan mo.”

“Tsinelas” wasn’t a kitschy limerick on flip-flops; it was about the systemic injustices leveled against the poor. “Esem” wasn’t a love letter to leisure, but a reprimand of monolithic mall materialism. This knack for pragmatic paradox would persist later in his career, peaking perhaps in “Perpekto,” an ode not to disability, but the many ways we’re assailed by modern life to the point of disability.

“Noong nagsisimula ako sa pagbabanda at pagsusulat, [nandiyan] ‘yong mga kwento tungkol sa injustice, sa kahirapan, kwento ng mga ordinaryong Pilipino — hindi maganda ‘yong mga kwento. Tragic,” says Abay, afterwards rattling off the names of artists who have informed his craft in the university years: Gary Granada, Joey Ayala, Asin, and Buklod. The crowning moment of Yano-era Abay was, clearly, “Banal na Aso, Santong Kabayo,” a catalogue of hypocrisies akin to a Jose Rizal refresher: brazen, brash, brutal. The songs could trace their roots to the less manicured pockets of New Manila, where Abay spent his youth and where he first experienced different shades of the “assault of the everyday.”

“‘Yon ang pinagmulan ng ‘Banal na Aso’: ‘yong mga bagay na nakikita ng mata ko, [nahahagip ng] pandinig ko: ingay [at] baho ng siyudad.”

Each Abay incarnation was an attempt to be an involved chronicler, not a detached narrator. Even in lulls between eras, during breaks from rockstar-dom — and being a “rockstar” is something he embraces tongue-in-cheek, like a chest-thumping pro-wrestling heel — his multifaceted journey often involved difficult but necessary conversations: the inevitability of depression, the rote void of public life, the necessity of art during unrest.

Read the rest of the story in The State of Affairs issue of Rolling Stone Philippines. Buy a copy on Sari-Sari Shopping, or read the e-magazine now here.