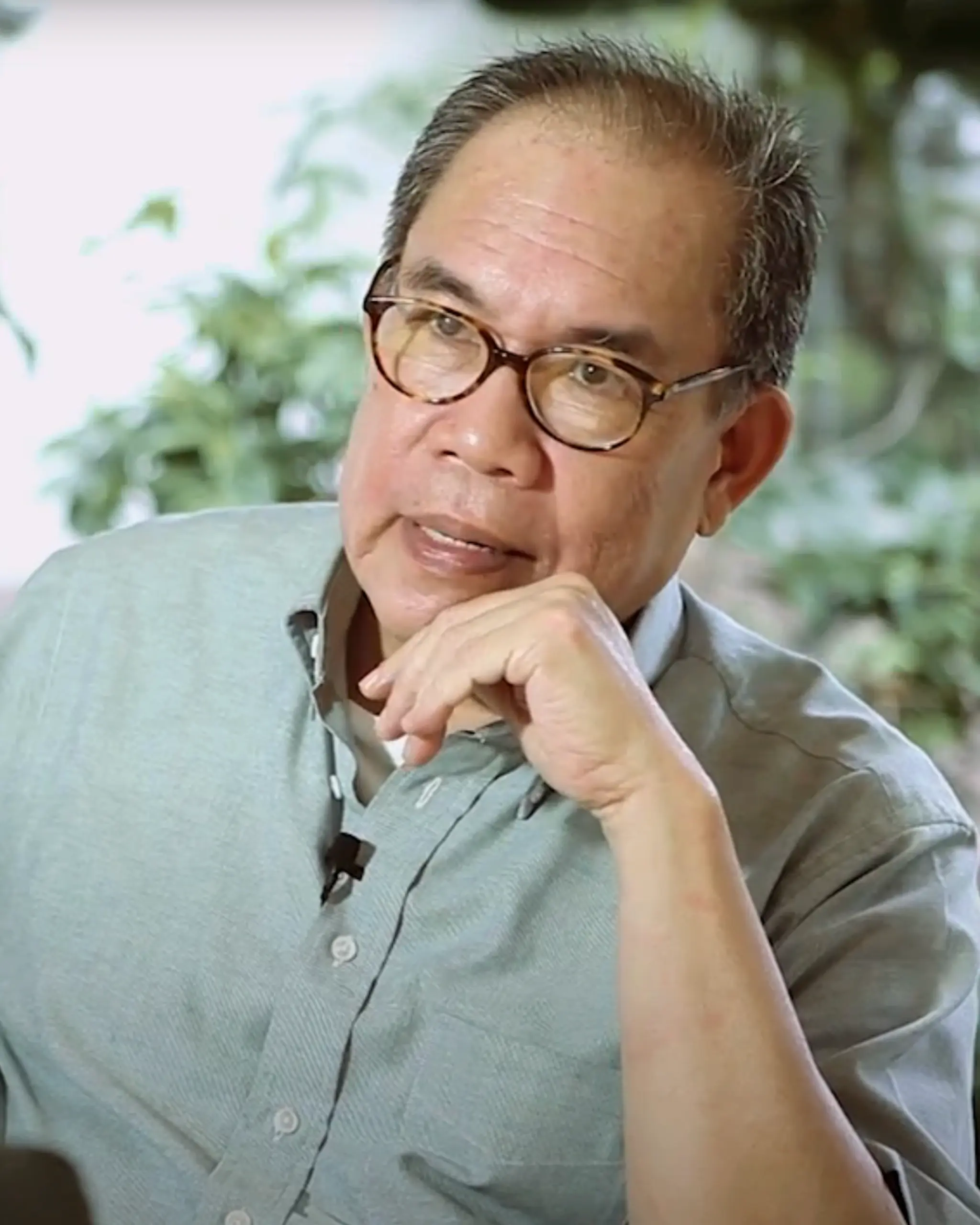

To Jose Dalisay, the realms of literature and martial law are almost inseparable.

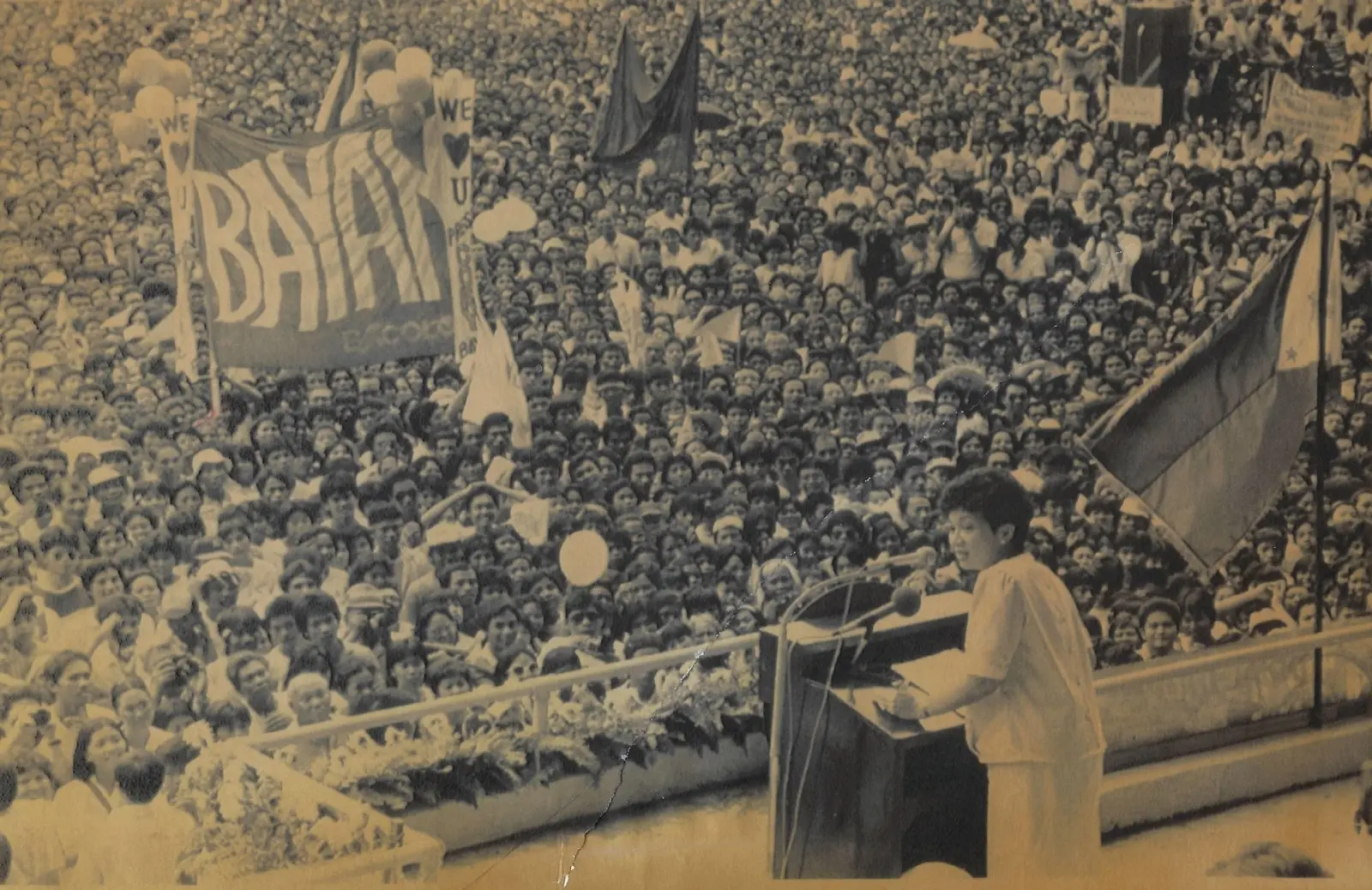

The Filipino author, whose novels such as Killing Time in a Warm Place and Soledad’s Sister have earned him accolades and acclaim over the course of his five-decade career, first joined the resistance against martial law when he was just 18. Although he had immersed himself in the student activist movement at the University of the Philippines (UP) as a freshman in 1970, Dalisay eventually decided to drop out to pursue a career as a reporter.

“In those days, it was hard for me to distinguish between being a journalist and an activist,” Dalisay told Rolling Stone Philippines. “I tried my best to be objective, but naturally my sympathies were with my comrades and friends on the left.”

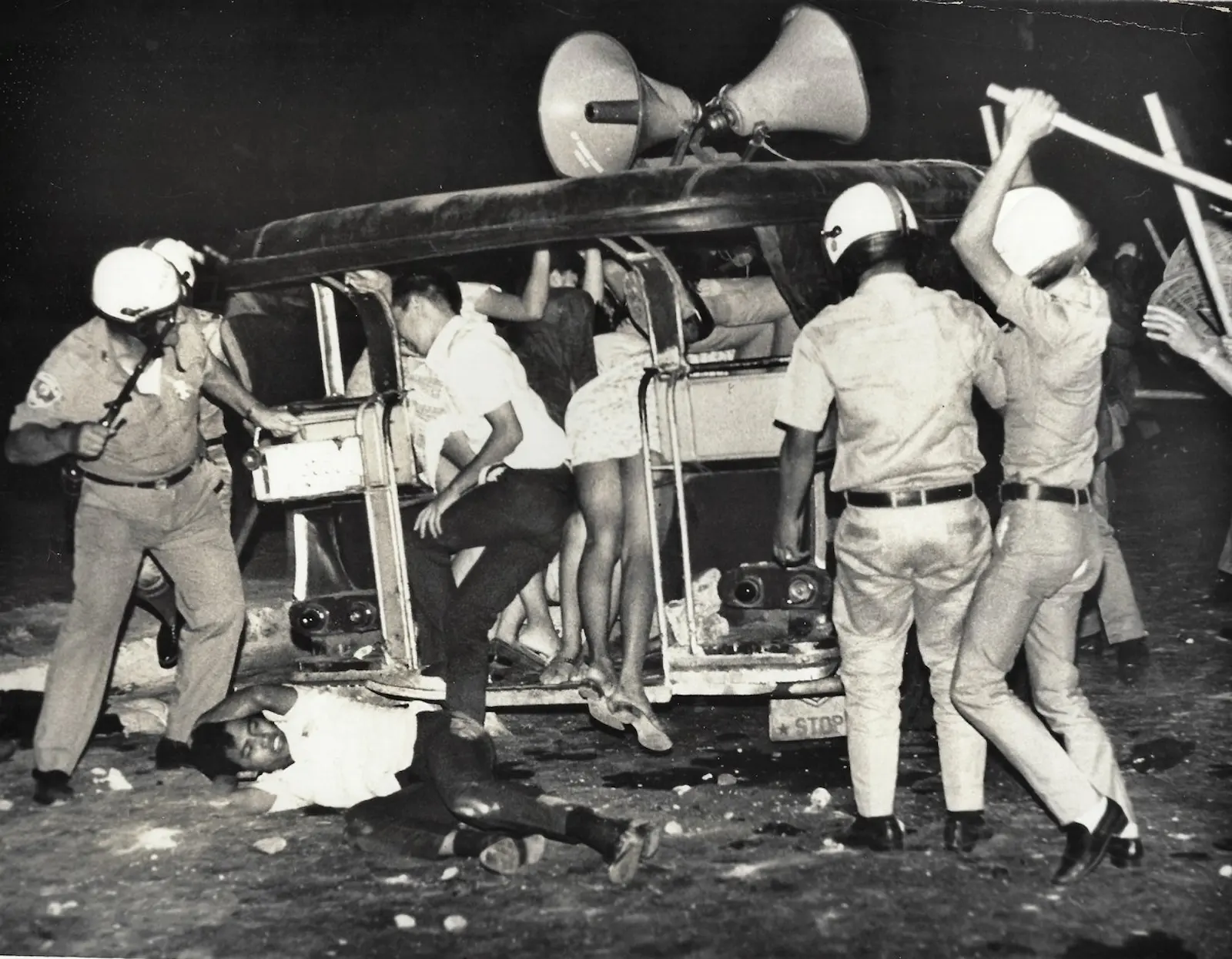

It was as a journalist for the newspaper Taliba that Dalisay found himself on UP’s campus on the evening of the declaration of martial law. “At some point, I heard gunfire,” Dalisay recalled. “There had been rumors that martial law was going to be declared, and when I heard those shots, I presumed it had something to do with that, but nobody knew what was really happening.”

“My first instinct was to call my office,” Dalisay continued. “Here I thought I had a scoop! At 18 years old, there I was in the middle of what could be a very big story. So I called my boss, but he said, ‘Hey, wala na tayong diaryo. Kami nandito, tinututukan na. It’s martial law na.’ And that’s how I discovered that martial law had been declared and that I no longer had an office to report to. My journalism career was suddenly over.”

Because of his contributions to the resistance, Dalisay was eventually incarcerated for seven months. After his release, the author went on to write his debut novel, Killing Time in a Warm Place, a work which draws heavily from his time in prison. Its protagonist Noel, like Dalisay, finds himself in the middle of student protests and rallies at the height of martial law, only to be arrested and forced to leave the movement.

The novel, published in 1992, won the 1993 National Book Award for Fiction, earned the title of Co-Winner of that year’s Palanca Grand Prize for the Novel, and won the UP President’s Award for Most Outstanding Publication. Most recently, in 2024, Killing Time in a Warm Place was released in German translation.

For the 53rd anniversary of martial law, Dalisay sat down with Rolling Stone Philippines to look back on his time as a student activist, his experience in incarceration, and the necessity to continue writing about the truth in the face of historical revisionism, misinformation, and political oppression.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

You once described your experience being incarcerated and then released as “something straight out of Kafka.” How so?

[After martial law was declared], I found a job working for the office of Mayor Nemesio Yabut in Makati… he took us in, and we did the strangest things. Our formal job was to check the attendance of street sweepers in the morning, which was really an excuse to give us a small salary to tide us over. I was at that job, but I was also still connected to my friends in the resistance. I was in a kind of limbo.

Even though I was sort of hiding out, on Christmas 1972, like a good son, I went home to spend the holiday with my family. I had some drinks with my neighbors, but I had no idea that one of them was a military asset — an agent. Shortly after the New Year, around midnight, my father woke me up, and I woke up to the sight of a carbine gun being pointed at me. There were half a dozen officers around me.

And so began seven months plus of martial law imprisonment in what is now [Bonifacio Global City]. It’s kind of ironic that we think of BGC as the cutting edge of modernity in our social life today, but back then, BGC was a prison for us in the middle of nothing. We occupied the barracks there, and later on, I was moved to maximum security for some reason. I still see that building now — I think our old prison is now where S&R is.

“People like me who write novels and stories about martial law… well, we might as well be writing about ancient history to many young people today. I very often have to emphasize that martial law was even further to Gen Z or to millennials than World War II was to us boomers.”

Mind you, there was no trial, no anything: there was just what was called an ASSO, or Arrest, Search, and Seizure Order, issued by then [Secretary of Defense Juan Ponce] Enrile.

And then one day, I was in the shower and heard my name being called to the guardhouse. I thought, “Boy, am I in trouble again?” Because the one time that happened to me earlier was when I got beaten up by some drunk jail guards for fun. I thought it was kind of early in the day for a beating.

But I went to the guardhouse, and the army captain pulled out my [record] and said, “Dalisay, pack up. You shouldn’t be here because we have nothing on you.” And just like that, I was released.

I went home to UP. The strangest thing was that as soon as I got there, I sat on the A.S. steps [Arts and Sciences] and everything was deafeningly quiet. Nobody was there. UP was a ghost town.

Your novel, Killing Time in a Warm Place, takes a lot of inspiration from your time in incarceration during martial law. More than 30 years since the novel was published, how do you see it continuing to resonate with readers?

When President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. was elected a few years ago, like many people from the First Quarter Storm, I was stunned. I couldn’t believe that we had gone back to where we were half a century ago, like nothing had happened.

Someone asked me, “Aren’t you thinking of writing a sequel to Killing Time in a Warm Place?” And my answer was, “I mean, what for?” It’s just going to be the same thing all over again. Or, well, as it’s turned out, maybe not quite the same thing.

But the ironies of history here in the Philippines are very, very striking. Of course, the Marcos restoration is the centerpiece of that. But also, sadly, the empathy and ignorance of many of our people to the dangers of authoritarianism. This goes beyond the Marcoses. Our experiences with his predecessor, [former president] Rodrigo Duterte, should have awakened us to that. It’s like we never learned.

How important is it, given today’s politics, to weave literature into the preservation of martial law’s history?

The basic job of literature is to tell the truth in as many ways as possible. But the truth is a very complicated thing. It’s not just one thing. It could be many different truths for many people. But what is important is to get the conversation going. Not just between the reader and the author, but between the reader and the history and the present.

People like me who write novels and stories about martial law… well, we might as well be writing about ancient history to many young people today. I very often have to emphasize that martial law was even further to Gen Z or to millennials than World War II was to us boomers.

Are you saying that it’s a struggle to educate the younger generation about martial law?

There’s a part of me that can’t blame young people. They’re not even supposed to remember martial law because how can you remember something you never knew?

But who else is going to do this job of reminding people of the dangers that we face as a nation, if not us novelists and writers and journalists? We keep the past alive, not for its own sake, but as a reference point. This isn’t just nostalgia for its own sake. [Writing] is really an obligation to learn and to understand what happened to us so that we don’t make the same mistakes.

You once described all conversations surrounding martial law as an “echo chamber.” Do you feel that still holds true today, and if so, how do we escape the echo chamber?

There are many conversations that can be had about martial law. For those of us who went through it, we have our own language and shorthands when discussing it, and… there’s a lot that we still have to process.

But there are some basic things that we all share and understand. The more important conversation, really, is between us and young people. I think that’s where we’re having some difficulty. First of all, we don’t know your language. We don’t know how to pitch to you or send a message to you. And I think we definitely shouldn’t be starting our conversations with, “Back in my time,” because that’s an instant turn-off.

But other than [connecting] with the youth, we also need to step away from our preconceived notions, one of which is that people have a natural resistance to authoritarianism. That may not be true. Most people actually accept [authoritarianism], and may even feel comfortable with it.

“It’s the vocal few who create an impression, and it’s important to do that, especially if you’re in the minority: you need to make more noise.”

One point that I always raise about martial law is that during that time, those who resisted martial law were in the minority. And if you think of us, or yourselves, as “rebels,” we will always be in the minority. Most people will simply go with the flow, and we Pinoys are great at that. We adapt, we accommodate, and we accept. Those of us who make noise, resist, and try to change things are not as popular as we may think we are.

For example, we think of UP as this bastion of radicalism during martial law, but it wasn’t. Most UP students, even during the First Quarter Storm, went to class, got their degrees, and didn’t join any demonstrations.

It’s the vocal few who create an impression, and it’s important to do that, especially if you’re in the minority: you need to make more noise.

But you shouldn’t imagine that, as the [minority], there will be any popular support. I think the very fact that we’ve technically struggled for 50 years tells you that we didn’t have the kind of support that we anticipated we would.