On Sept. 20, 2024, the eve of martial law’s declaration more than fifty years ago, Kiri Dalena attended the awarding of the Gawad Cultural Center of the Philippines Para sa Sining. It was a night honoring individuals who have spent a life excelling in the arts, like Dalena’s mother, Julie Lluch, who received the Gawad for the visual arts. Representing President Ferdinand “Bong-bong” Marcos Jr., his sister Irene Marcos-Araneta gave lofty remarks on how arts and culture flourished during their parents’ time. The atmosphere was “civil but tense,” Dalena says, looking back at the time. “We were uncertain about [the awards] because it’s under the Marcos administration. It’s always these platforms, which are complicated.”

When Pete Lacaba — poet, activist, and a political prisoner during the martial law years — came onstage to receive his award, his acceptance speech sent out a thunderbolt. The honoree for literature did not mince words. Lacaba broached the issue of extrajudicial killings, the disappearance of activists, red-tagging, white-washing, the killing of his brother, the poet Eman Lacaba, during the Marcos years, and the role of artists to continue the struggle. “Pinapaliguan ng pabango ang malalansang mga programa ng diktador Marcos,” he said.

A fire among artists was lit. Intuitively, Dalena, who had been in the rightmost corner away from Marcos at the front, began to chant: “Artista ng bayan, ngayon ay lumalaban!” People responded, “Ngayon ay lum- alaban, artista ng bayan!” As Lacaba descended the stage, the room throbbed with applause and the fiery chorus of disbelieving, defiant chanting.

“It’s not easy to get into these spaces. You take the risk even if it’s a small risk. It was worth doing just to say something,” Dalena says. She knows just how tense, how tricky, how glaringly self-contradictory these spaces could be, she, who had been straddling the grounds of art and activism all her life. When Dalena paraphrased her mother’s own acceptance speech, which insists on the role “of the artist as a citizen” and the responsibility of “empathizing and connecting with the most abused,” she might have well been describing her own commitment to the calling.

The Stakes of Expression

Born to Lluch, the pioneering sculptor who expressed feminist ideas in lively terracotta, and to Danilo Dalena, the political cartoonist and painter who depicted the hurtling mass of the labor class in austere expressionism, it’s clear that the younger Dalena had art in her blood. But she also grew up knowing that art came with fatal costs.

“We have this concept of activist as a very high, very elevated vocation because our concept of activism was [rooted] in the ‘70s, when activists would really be imprisoned or even killed.”

“We essentially grew up with [Pete’s] family,” she says. Lacaba and her father worked at the Philippines Free Press along with the likes of Nick Joaquin and Wilfrido Nolledo. They went on to establish the publication Asia-Philippines Leader, where her father thrived as a political cartoonist. It would operate for a year before martial law closed it down. “My father was questioned but not put in prison,” Dalena recalls. “When [the Lacabas] were in prison — not just Pete, but when some of his siblings had to go in hiding or [were] killed — we knew about those things.”

Dalena is remembering her childhood in an airy, light-filled room in Berlin. As we speak on Zoom, we track the detours and waypoints in her life that have led to activism. “We have this concept of activist as a very high, very elevated vocation,” she says, “because our concept of activism was [rooted] in the ‘70s, when activists would really be imprisoned or even killed.”

When Dalena co-founded Respond and Break the Silence Against the Killings (RESBAK) around 2016 to 2017, they didn’t contend with the same lethal atmosphere of repression, but they came upon a different dynamic of violence and fragility. An alliance of artists, media practitioners, and cultural workers, RESBAK began as a way to protest then-President Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs through efforts as diverse as exhibitions, videos, zines, and workshops. Over time, they’ve come to support and work directly with the families of EJK victims: mothers who lost a son, the widowed women. “It started na they were so fearful, so afraid of showing their faces,” Dalena remembers. When they organized a protest in 2017, “Doon lumakas ang loob ng survivors to talk in public.”

Staying in Germany for a few weeks, Dalena is in the middle of organizing more talks, gatherings, and activations. “Kanina lang, natapos ang visa interviews. We are trying to bring two family members to The Hague.” Since Duterte’s arrest and surrender to the International Criminal Court, there was a clear shift in atmosphere. “Kahit na hindi pa rin sigurado — we still have to guard these hearings sa ICC — it’s really giving hope, which eight years ago was impossible to think about.”

Back in June 2022, shortly after the transition to a Marcos presidency, Dalena was in Kassel, Germany as a Filipino participant at documenta, one of the most influential global art exhibitions. At the opening, she and several other RESBAK members unfurled a “STOP THE KILLINGS” banner, the letters made of a thousand mourning pins. “When I’m in Germany, I take advantage of my being here. That’s how we’re able to create connections for RESBAK. When I was here for documenta, we held talks and actions about the drug war. That already began years ago, spreading information about what was happening in the Philippines.”

“Noong panahon na ‘yon, when you say may human rights violations, it’s like it’s considered black propaganda; na it’s not true kasi tapos na ‘yon. It’s not [propaganda. The violations] were still happening.”

The plan is to come together again in Germany this September, leading up to Duterte’s next trial hearing. The two family members will work with the Duterte Panagutin network, a coalition of organizations across Europe campaigning for Duterte’s accountability through conferences and protest demonstrations. Some of the transnational alliances involved are Gabriela, the progressive women’s organization, and ALPAS Pilipinas, which mobilizes the Filipino community in Berlin.

“We’ll hold talks in universities here in Berlin, then there will be a bus, and we will all go to The Hague,” says Dalena. “This is a very important historic moment, and we want them to be able to witness it.”

An Activist’s Lens

Several of Dalena’s works are in themselves forms of witnessing, a way of standing close, side by side with history as it happens. She has shot the rage and mourning around the Maguindanao massacre (Requiem for M, 2010), followed children orphaned after Typhoon Sendong (Tungkung Langit, 2013), and filmed a community facing trauma from Duterte’s war on drugs (Alunsina, 2020). Moving images like these point sharply at one particular malevolence after another, while others have an intensity that pierces across time, like Melfe Ebalang, an activist from Bukidnon singing a song of lamentation about poverty among farmers, with Dalena’s lens locked starkly on her face (Mag-uuma (Farmer), 2014).

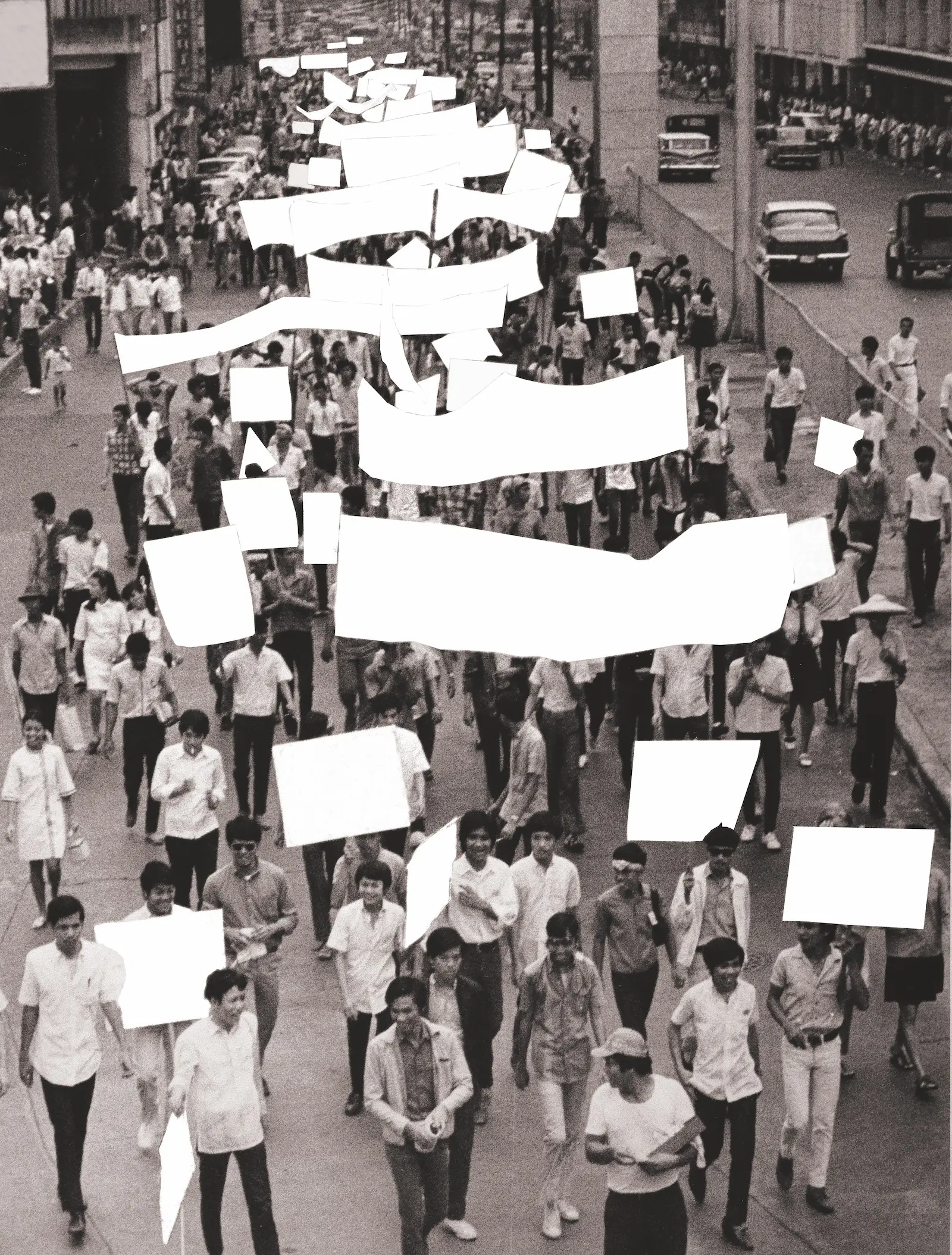

Still, one of her most circulated works is Erased Slogans. Started in 2008, the series speaks to censorship during martial law, but it has an uncanniness that evokes other authoritarian regimes. From an archive of news photographs, she pulled out images of mass mobilizations. Digitally altering the photographs, Dalena unraveled a world of anomalous silence, where every placard, banner, and picket sign showed no word of protest but appeared as a blank space. There is something uncannily restrained, even cinematic, resulting from the erasure, as though a great historical sequence unfolds, then flails against the weight of its own unreality.

When Dalena received the CCP Thirteen Artists Awards in 2012, the catalogue identified in her work “a poetic lyricism stemming from filmic language.” She has worked in multiple genres, but it is the lens — and all it aligns with: film, photograph, document, truth — that remains her work’s aesthetic axis.

“I really did not learn the history of photography in school,” says Dalena. “I learned through people who were very much not just photographers but human rights activists.” Having been raised during Marcos’ time, within the milieu of Lacaba, so extreme was the dual force of repression and resistance in her childhood that when Dalena was studying at the university in the sanguine years of the early ‘90s, she admitted thinking that activism was a thing of the past. “Noong panahon na ‘yon, when you say may human rights violations, it’s like it’s considered black propaganda; na it’s not true kasi tapos na ‘yon,” she says. Only when she graduated and decided to live in the regions as a full-time activist that she realized, “It’s not [propaganda. The violations] were still happening.”

Read the rest of the story in the Arts and Culture issue of Rolling Stone Philippines. Get a copy on Sari-Sari Shopping, or read the e-magazine now here.