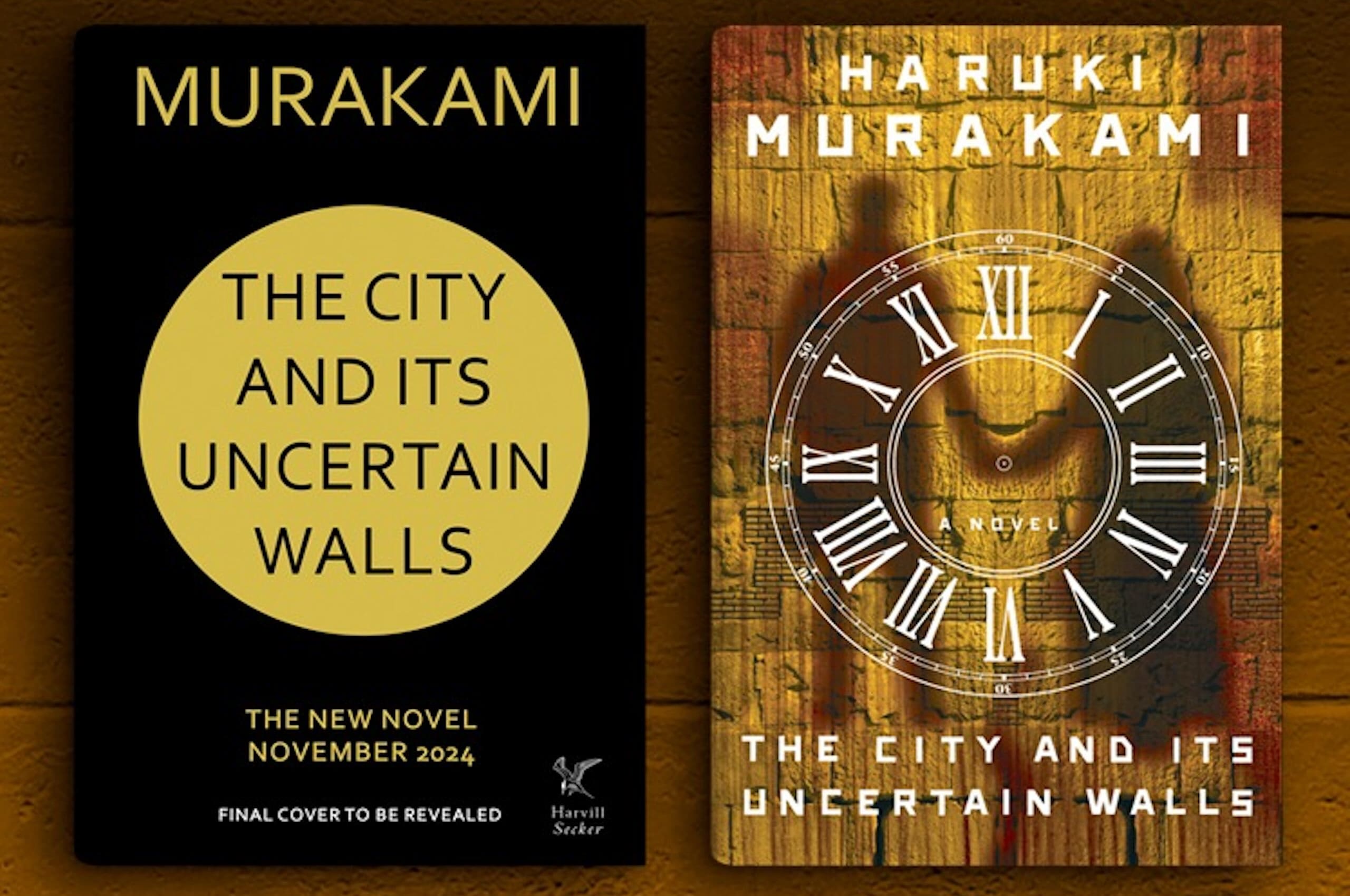

Haruki Murakami’s fifteenth novel is the Japanese author’s third attempt at writing the same story. Over forty years ago, a young Murakami had just made the career pivot from debt-ridden jazz club owner to striving fiction writer. In 1980, he published The City and Its Uncertain Walls as a novella in a literary magazine, but Murakami was so dissatisfied with his writing that he has since refused to allow anyone to translate the novella or publish it as a book. “That dissatisfaction stuck in my throat like a small fish bone,” Murakami said in an interview with The New Yorker, “a sort of loose end for me as a writer.”

In 1985, Murakami took the same universe he’d written for his novella and used it as the main stage for his breakthrough novel, Hard-Boiled Wonderland And The End Of The World. The novel was a strange, delightfully confusing amalgamation of two narratives: the odd-numbered Hard-Boiled chapters focus on a human data processor who finds out that his consciousness will soon disappear forever, while the even-numbered End of the World chapters center around a walled town, unicorns, detachable shadows, and a library that stores egg-shaped dreams instead of books. Despite the novel receiving critical acclaim and winning the 1985 Tanizaki Prize (one of Japan’s most coveted literary awards), Murakami was once again dissatisfied. “I was still young,” Murakami said in the same New Yorker interview, “and my storytelling stance tended to be a bit impulsive.”

Murakami’s tropes

The City and Its Uncertain Walls, Murakami’s latest attempt at revisiting his novella, feels less like a fresh addition to the author’s oeuvre and more like an echo of all of Murakami’s work. Even the most inattentive Murakami fans can recognize Murakami’s favorite tropes in his latest novel’s plot — which, although just as convoluted as those of his past novels, fails to completely keep readers engaged.

Uncertain Walls already begins with classic Murakami tropes: a lonely, brooding teenage boy falls in love with a mysterious, unconventionally attractive teenage girl (who is later hypersexualized, which in itself is a Murakami trope). However, their romance is cut short when the girl disappears to a walled town, where the “real” version of herself works in a library that stores egg-shaped dreams instead of books, and where unicorns and detachable shadows are completely normal (these similarities between Uncertain Walls and Hard-Boiled Wonderland is no coincidence).

The rest of the novel sees Murakami switching between two worlds, attempting to blur the lines between them. The boy becomes a middle-aged man and decides to venture into the “real” world and look for his lost love. However, he finds that the girl does not remember him and is stuck as a 16-year old version of herself (which, considering the age gap between them, is very creepy). Dissatisfied, the man returns to the “not real” world to hide away in the library of a far away town. Although the switching between worlds starts out as an interesting and very Murakami-esque plot device, the author spread himself thin by creating two realities, rather than sticking to one world and fleshing it out completely. The ambiguity between what is real and not real quickly became tedious.

Nothing new

The issue with The City and Its Uncertain Walls is that there’s nothing new — from its surreal plotline, familiar character archetypes to blending of both real and not real words. In earlier novels like Hard-Boiled Wonderland, Kafka on the Shore, and 1Q84, Murakami wielded surrealism effectively, knowing exactly when to use the style to drive a point or underscore an important message for the reader. In Uncertain Walls, fantastical moments — specifically those set in the “real” world — feel overdone, including tropes for the sake of including tropes. The visuals of the surreal walled town — a high wall separating the protagonist from his youth and true love, dark shadows that can weigh people down if not detached, a giant clock that has no hands because time doesn’t exist in the “real” world — seem to tell their metaphors too obviously, leaving little or no room for the reader to imagine what any of it means.

It is a pity. Uncertain Walls shows Murakami honing his writing style and improving on his already distinct narrative voice. While he isn’t the perfect writer, no one can deny that Murakami has dedicated more than 40 years to working on his craft and has become a powerhouse in the world of global fiction. It is because of that very same dedication to craft that Murakami, now in the twilight of his writing career, has chosen to revisit old works and endeavor to make them anew. With his third attempt to tell the same story, you can’t help but wonder whether it is time for Murakami to swallow his dissatisfaction and tell a new story. It is as if the author has trapped himself in his own walled town and refuses to let himself move on.