Walking into the Rainbow Ball, one of the biggest pride balls in the Philippines and across Asia, I instantly realize I am underdressed. As I stand awkwardly by the main doorway, wearing nothing but a slip dress, flats, and the lightest shade of eye shadow known to man, Shooting Gallery Studios comes alive with drag performers and dancers getting into their full regalia.

I spot six-inch stilettos, sharp five-piece suits, and so much body glitter that I don’t know where skin ends and sparkle begins. I catch one queen twisting balloons around their body to turn themselves into a living balloon animal. A drag king waltzes past in an oversized blazer and bedazzled platform sneakers. Compared to these divas, I am naked.

Since its virtual debut back in 2021, the Rainbow Ball has grown to reshape the ballroom scene in the Philippines and beyond. Led by International Mother Xyza Mizrahi of the first international voguing house of the Philippines, the House of Mizrahi, and Father Misha De La Blanca, who spearheaded dance studio We Are Shapeshifters, the ball is where local and international performers can safely sashay across the runway and bring their A-game onto the dance floor.

“When I first visited New York in 2015, the Philippines really didn’t have a ball scene,” Mother Xyza tells me. Although she has reassured me that the ball is “chill” and that I shouldn’t worry about not fitting in, she is also adjusting a giant hula hoop that will later hoist her into the air for a lengthy, complex, and not-very-chill-at-all acrobatic dance number. “That really got me, which was why I’ve worked hard to grow the scene here. Now it’s ten years later, and we’ve flown in eight Icons from New York to judge this year’s ball.”

I nod along, trying to figure out if she means “icon” as a compliment or as a genuine title. It’s only later when I bump into a dancer from New Zealand with cheekbones carved like marble that I get a crash course in the strict hierarchies of the ball scene. “The ‘Icon’ is like the house’s blueprint,” the dancer, who chose to stay anonymous, tells me, breaking it down for me with easy, small words and big hand gestures. “They’re a big deal.” He isn’t exaggerating: Icons are the pillars of their houses and have led the scene for at least 20 years.

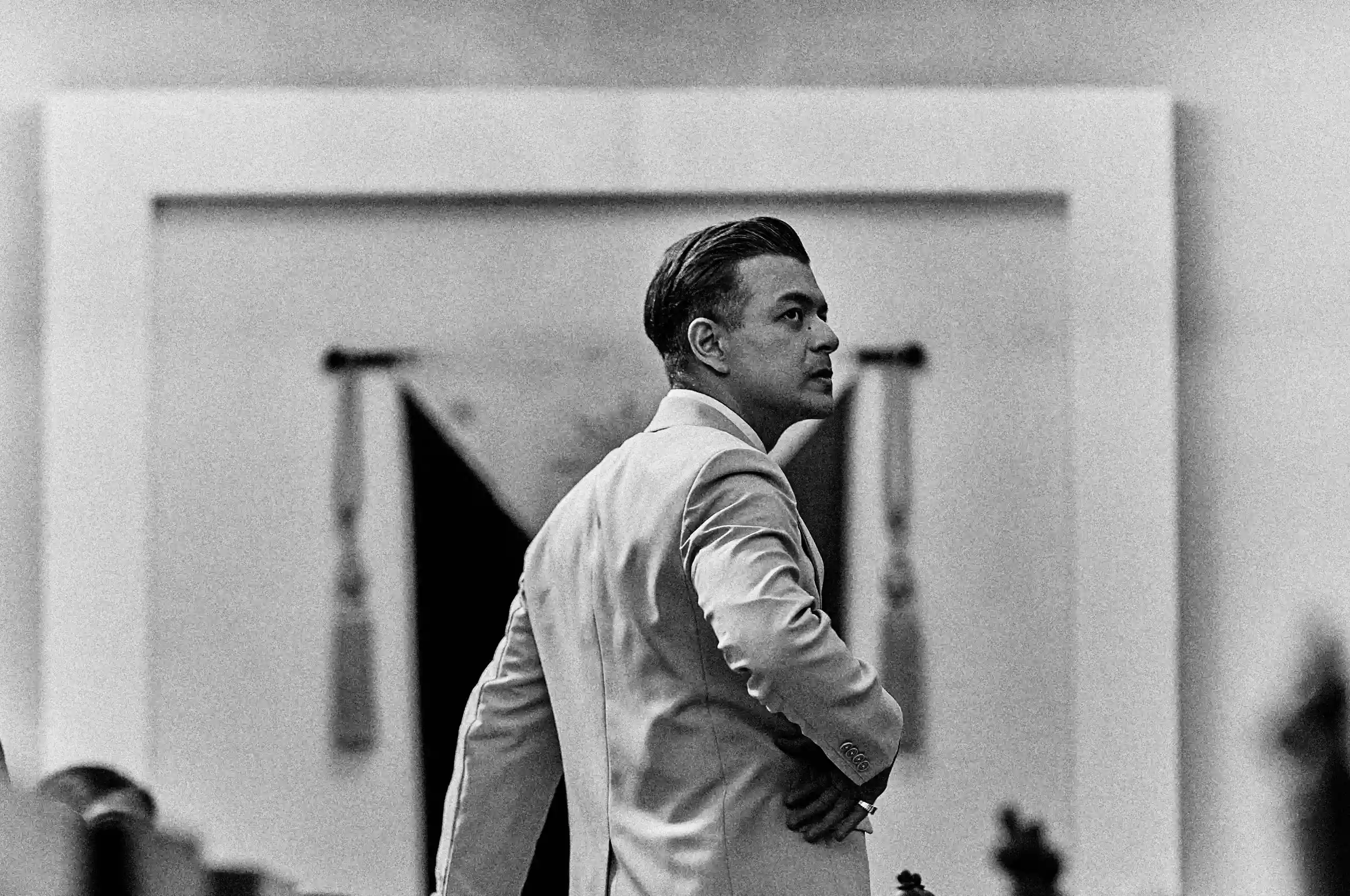

When I ask him what category he’s performing in at the ball, the dancer tells me he’ll be serving “Face.” When he realizes that I’m waiting for him to explain what that means, he says, “Okay, look at me: My category is all about selling my face. Obviously, your face matters. You need to have a good-looking face. But what’s more important is how you get people to look at your face, you know?” Looking at his high cheekbones, chiseled enough to cut glass, I can’t help but agree.

I find comfort in the fact that I’m not the only first-time attendee at the Rainbow Ball. “We flew in from Cebu just for this,” one dancer named JB tells me in Bisaya. JB, along with several members of the dance group Ballroom Culture Cebu, have arrived carrying tiny corsets, brightly colored tutus, and enough body paint to make sure they survive the night. It’s the group’s first time walking a Manila ball, and although they’ve been working to grow the burgeoning ball scene in their hometown, the stakes are high with the Icons judging the ball’s categories.

The Rainbow Ball truly begins when the LSS, or “Legends, Statements, Stars,” commences. Part roll call and part opening ceremony, the LSS is where competing houses, groups, and even solo acts take to the stage to prove that they deserve to be seen. Icon Koppi Mizrahi holds down a steady background beat while Host Freya Mizrahi and Master of Ceremonies Kinshasa Basquiat riff off each entrance with improvised chants. Each house is dressed in their respective colors: the House of Ninja all don aggressive shades of red; the House of Labeija in bright yellow, while the House of Mizrahi in violet carnival attire, playing on the ball’s loose theme of “Carnavale.”

From there, the stage turns into a flurry of categories. In “Realness,” trans women strut the runway in floor-length gowns, radiating high femme glamour. Tension spikes when a queen in a “Miss Surigao del Norte” sash clashes with another in a gold bikini and “Miss Manila” sash, both battling for the judges’ gaze. They get close to the table, blow kisses, and snap fingers, but the Icons stay stone-faced, coolly scoring in silence.

In “Perfect 10s,” a string of performers make their way onto the stage, either exuding the “perfect” masculine or feminine body. One dancer from the Japanese chapter of House of Ninja flexes his muscles, slathered in body oil, as he vogues and duck walks up to the judges. A Filipino performer, rolling his belly with pride, commands the stage with full-body stomps and lunges.

A stand-out segment of the night is “Allstyles to A Vogue Beat,” which Icon Andre Mizrahi lauds as the “best part of every Rainbow Ball.” Performers go toe-to-toe, pulling from their personal arsenals of poses and moves to prove who deserves the category honor. Against the rapid hip-hop footwork of one Filipino drag king, one American soloist shows off his fast-paced “New Way” hand poses, which are more stunty and cunty in style — a contrast to the geometric movements of the Old Way of voguing. Two Japanese sisters from the same house get into a diva-off, voguing around each other in circles until the judges decide who’ll take the win. Two Korean pop-and-lockers make it to the final round, and the Icons have to stand to make sure their footwork is on point. One dancer misses a beat, and the crowd roars when the Icons choose their victor.

As the night went on, my anxieties at the start of the night quickly faded away. As a safe space for many queer performers and artists to be themselves, the Rainbow Ball has fostered a space to not just witness the spectacle, but to be a part of it. With its fifth edition now under wraps, the Rainbow Ball has proven once again that everyone is welcome on the dancefloor.