Asog is the type of movie so tangled in contentious drama that most people have heard whispers of it, yet almost no one has seen it. For one, the docu-comedy was screened just once in 2023, tucked away in a single cinema at Ayala Malls Manila Bay during Cinemalaya Film Festival. For another, because the film delves deep into the heated land dispute between the people of Sicogon Island and Ayala Land, Inc. (ALI), there have been accusations of the giant conglomerate actively blocking the movie from being seen.

Although Asog has made the rounds around the international film festival circuit, even making it into the official selection at the 2023 Cannes Docs-in-Progress showcase, it has yet to secure a wider public screening in the Philippines. Locally, Asog has turned into a cinematic phantom: whispered about in film circles, praised by foreign audiences, but eerily absent from our own screens.

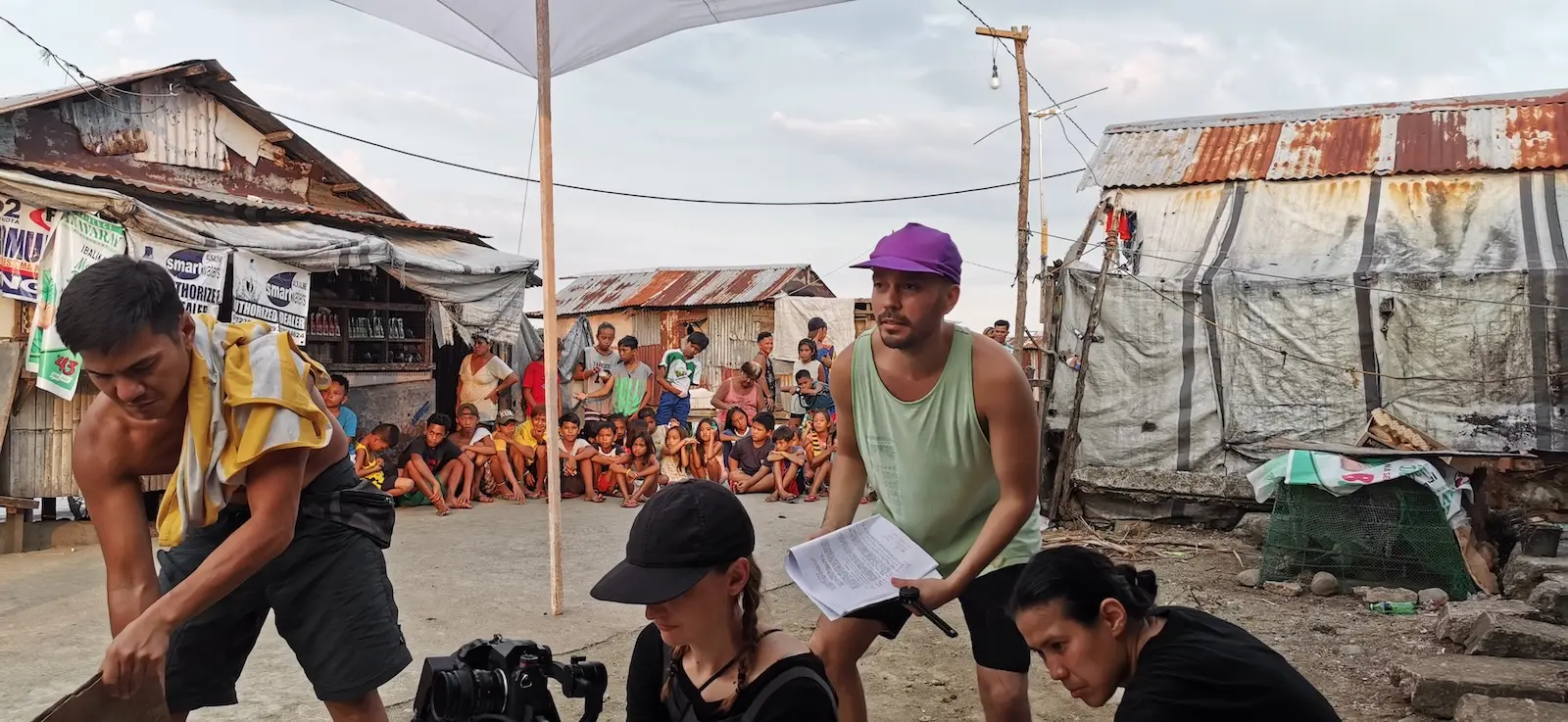

But what exactly is it about Asog that makes it so controversial? The actual plot of the movie is less a hard-nosed exposé and more an existential road trip turned buddy caper. It follows Jaya (Rey “Jaya” Aclao), a teacher whose career as a late-night television show host and comedian was abruptly ended by the devastation of Typhoon Yolanda. In one last grab at fame, Jaya decides to go on a road trip to Sicogon to compete in a small-time beauty pageant. They embark on the journey with Arnel (Arnel Pablo), a high school student consumed by the grief of his mother’s recent passing. While both grapple with their own grief, it is their evolving friendship that lends Asog its lighthearted, wholesome charm. Their road trip story often feels like a quirky, heartfelt adventure straight out of Little Miss Sunshine or The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert.

However, the film also explores the real lives of the Sicogon people in the aftermath of Yolanda. In 2013, just after the natural disaster had ravaged the region, ALI and Sicogon Development Corp. (SIDECO) reportedly blocked 6,000 Sicogon residents from returning to their homes. The two corporations allegedly did this to clear the land to develop an airport and luxury resort; however, 784 families refused to leave, and Asog shines a light on their stories.

Although ALI and SIDECO eventually offered the remaining residents reparations, funding the construction of homes for them (and, notably, only after Asog was greenlit for production), the minds behind Asog took to social media to spotlight how ALI had sabotaged the film’s national premiere. In an Instagram post, director Sean Devlin argued that because Asog was screened at an Ayala Mall cinema, ALI purposefully made it difficult for movie attendees to purchase tickets for the film. What’s more, the one screening of Asog included a cryptic message from ALI, which emphasized how the corporation was in “regular contact” with the Sicogon community. Devlin demanded that ALI immediately return the community’s legal titles to their own lands, while also paying the 32 million pesos in financial reparations still owed to them. Within 48 hours of the post, ALI paid the overdue amount in reparation funding for the construction of more homes on the island.

“The crazy thing was, one of Ayala’s [representatives] told us that they wanted our movie to ‘have a happy ending,’” Devlin told Rolling Stone Philippines. Despite the film’s packed schedule — with screenings set for the Brooklyn Museum this June and 14 cinemas across Canada in August — the director still found time to reflect on his controversial film from two years ago. “I would have just loved for everyone in the Philippines to have experienced the movie drama-free.”

In this hour-long interview with Rolling Stone Philippines, Devlin reflects on the experience of making Asog, the joy of spotlighting the stories of the Sicogon people, and his genuine surprise at the controversy the film eventually stirred.

This interview has been edited for brevity.

Asog, despite the natural disaster and tragedy it focuses on, is a surprisingly comedic movie. What are your thoughts on Filipino comedy when it’s used in the face of collective trauma?

My background is in comedy. I’ve been doing stand-up for over 20 years in Canada, and I do a lot of work with people who improvise. And with Filipinos, our shared experience is making other people laugh.

For Asog, I think its best moments were when the people in front of the camera were trying to make each other laugh. None of them were trained actors, not even Arnel or Jaya, and so they relied a lot on improv. For example, there’s an early scene where three women are trying to help Arnel plan a novena ceremony for his dead mother. Those were Arnel’s real neighbors, and they had all known his mother and had supported him when she really passed away. So there’s something very real about that scene, but we wanted them to act as if they were planning a party. When they got the joke, they got it — they started planning the novena like it was just a normal celebration where you get carried away about the details of food, flowers, decorations, everything.

There’s a darkness to Filipino comedy. We have [the] ability to laugh even when things are going wrong. There’s this willingness to find a reason to keep on laughing in the midst of sadness. The other side of my family are Irish, and there’s this old Irish bit that the best person you need at the funeral is the first person who’s willing to crack a joke: I think that person’s usually Filipino.

There’s a darkness to Filipino comedy. We have [the] ability to laugh even when things are going wrong.

The film also sees Filipinos cracking jokes not just in Filipino, but also in Bisaya. What was it like shooting Asog, where everyone was speaking in different languages?

We wanted everyone to speak in whichever [language] they felt most comfortable in, and so that’s what happened. Personally, I had to work through a translator to understand them. I was born and raised in Canada, and although my mother was from Leyte and could speak Tagalog, Cebuano, and Bisaya, she never taught me any of them. In Asog, a lot of my authorship was surrendered to the cast: I just gave them an outline of the script, but they’re really speaking in their own words.

What was the connection between you and Typhoon Yolanda?

When the typhoon struck, my mother was very in tune with the devastation of her hometown in Leyte. I felt really compelled to try and help somehow. A year later, I got my chance: I was invited to make a short documentary for Yolanda’s one-year anniversary with an alliance of Tacloban storm survivors called the People Surge. That was when I met Arnel and his family, whom I interviewed for the documentary. We were working with a little DSLR camera and maybe two to five people on our crew, but that was enough. That documentary turned into When the Storm Fades.

Did the people of Tacloban get to see the documentary?

Yeah, so funny thing. I’d been filming for a week, and I think it was because it was the storm’s anniversary, around 20,000 people were on the island of Tacloban. The organization that had brought me there pulled me aside and said, “Okay, we’re going to need you to show the film now.” And at first, I really didn’t want to. We weren’t ready! But they doubled down and said, “This is really important to them. We have to show them something.”

Looking back on it now, I realize how important it was for the survivors to really see themselves. I edited something really quick for them, not thinking it would be any good. But I think they were in awe, as most of them had never seen people who speak or look like them on TV.

After When the Storm Fades, you began working on Asog. Did you always know that you wanted to focus the film on Arnel and Jaya?

Yeah, it really started with the two of them. When we were making the documentary, I felt that I needed to laugh. As a comedian, it’s sort of a necessity. So, perhaps a bit inappropriately, I asked someone if there was a comedy show in town. And I was told I had to go see Jaya.

Jaya’s performance was incredible. They were performing at a little KTV bar, and their comedy set had so much singing, dancing, and karaoke. Jaya would invite people onstage to sing, and more often than not, they’d choose a song that had been a favorite of a loved one lost during Yolanda. They’d cry onstage, and Jaya would give them a space to grieve. But after walking them offstage, Jaya would return with jokes, and people would laugh again. This went on for hours. I had never seen anything like this, this act of using comedy to heal trauma.

With Arnel, I saw him posting some photos of himself in drag on Facebook. At this point, I’d known him for almost eight years, but I’d never really seen Arnel express himself in that way. After seeing those photos, I just felt that there was definitely a story there between Arnel and Jaya. Eventually, their friendship morphed into this fictional device that allowed us to explore the way a typhoon had affected all these different people.

Do you want to talk about the drama?

I think so. I’m fine with you asking any questions, and then I’ll just have to measure my responses and I’ll kind of explain why, but I think even the way that I need to be guarded, it’s also meaningful. My silence also means something.

Did you expect any of it to happen?

The thing is, our movie had absolutely no finger-pointing. I need to give credit to the community of Sicogon and to the Federation of Sicogon Island Farmers and Fisherfolks Association. For 11 years, they’ve represented the 784 families refusing to leave the island. And in Asog, it was actually their idea not to name Ayala Land in the film. They didn’t want to antagonize anyone; they still hoped for a peaceful resolution. So if you watch Asog, Ayala Land is never mentioned directly.

Things changed after the screening. It was the disclaimer. I think the Sicogon community felt that they were being told how to feel, and that was when the community gave us the permission to publicly name Ayala. To their credit, though, Ayala Land responded quickly and met the demand to pay the outstanding livelihood funds. However, 19 percent of the funds are still owed, as well as the agricultural and residential deeds to the land.

Looking back, do you wish none of the drama had happened?

Not really. If that’s what it took for Ayala Land to finally take action, then I’m okay with it. Of course, we’d love for everyone to experience the film without all the drama. But more than anything, we’re just happy the people of Sicogon are finally receiving what they’re owed.

The only thing I feel we’ve really missed out on is that Asog hasn’t had the local release we hoped for, and Jaya, in particular, hasn’t gotten the recognition they deserve. Jaya absolutely needs an agent in Manila. They’re a star, and the film proves it.

I guess it’s really up to Ayala Land on whether or not Asog will be seen in the country soon. We really wanted it to get a nationwide release since it was shown only once. It shouldn’t be controversial to tell the truth about what the people of Sicogon experienced.