At age 13, Gab Mejia was hiking towards the summit of Mount Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia with his father and older brothers. As they neared the peak, their journey came to a halt. His dad was experiencing hypothermia and one of his brothers was straining from stomach pain. Nonetheless, he attempted to continue alone.

A deep fog enshrouded Mejia as he went on. Surveying his surroundings, he saw nothing but mist and the rugged hiking boots on his feet. The forest began to die; soil transmuted into granite. The air was thin. He gasped for breath, but oxygen couldn’t seem to enter his lungs. There he was, 4,000 meters above ground, his head literally in the clouds, struggling to breathe.

Mejia failed to complete the summit, but what he saw way above the earth stayed with him. Now, at 27, he says that failing at the face of an ethereal world “led to a sense of curiosity that I had to unravel for myself… something seeped through my skin and told me to try and seek more mountains,” he tells me. “There’s no language for it.”

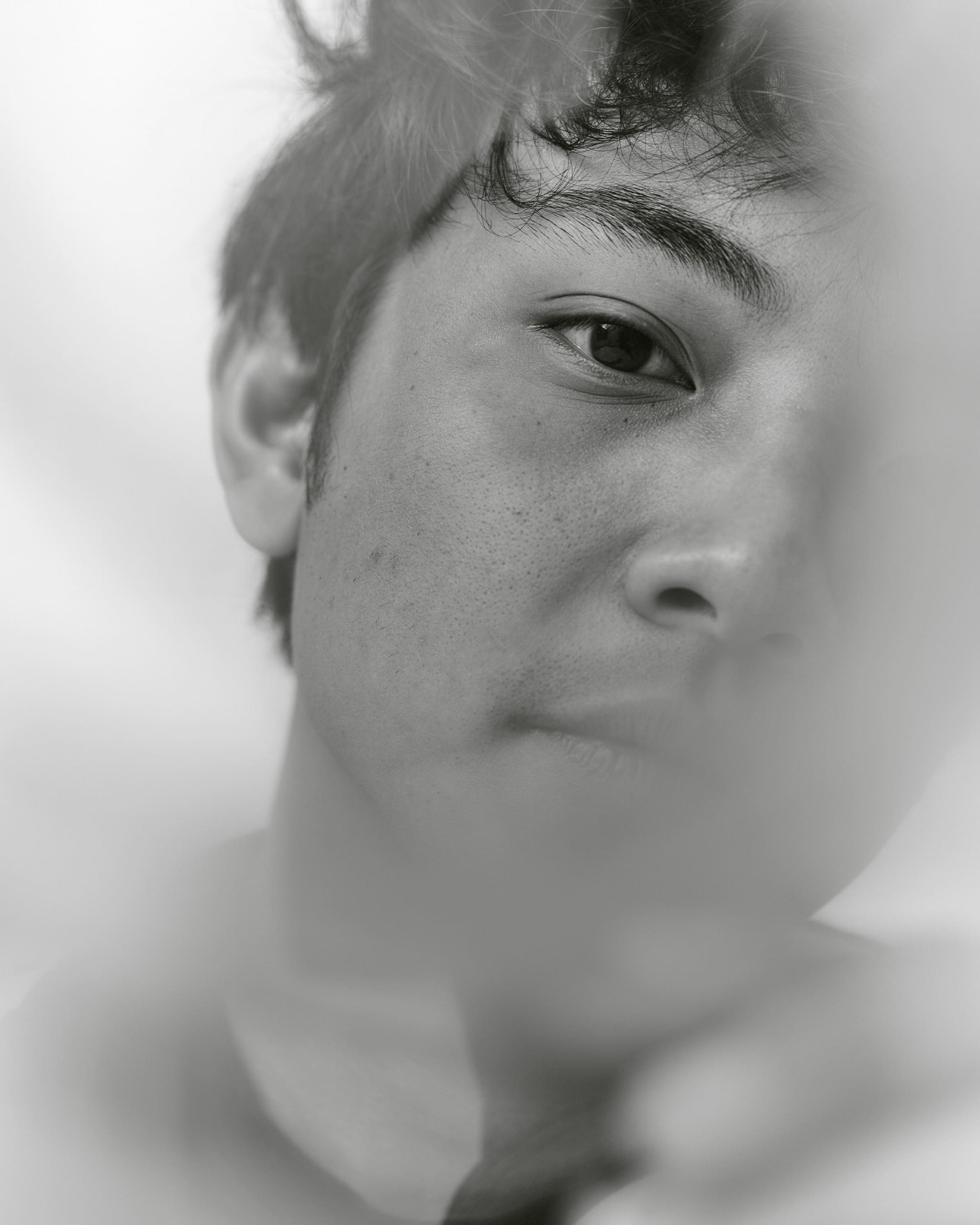

When I meet Mejia in person, we are in a completely different world: a cafe near Legazpi Park in Makati. Outside, the exhaust of air conditioning units and passing cars pollutes the air. Foul noise and harsh smells spoil the atmosphere.

“I don’t really like it here,” Mejia says, a bit cynically.

Instead, it’s in the mountains where Mejia always felt safe. He struggles to say how and why exactly, but settles with, “a lot of my becoming came from that.” While words fail Mejia, it’s clear his love for nature is something to be seen, not heard. After all, Mejia is a conservation photographer and National Geographic explorer, whose visual lexicon documents the climate crisis. He captures mountains, marshes, forests, and fields damaged by natural calamity in photos that land on the pages of National Geographic, BBC, CNN, Vogue Philippines, The Manila Times, Photo London, and more. Growing up as a child of nature influenced what Mejia eventually chose to do — “to take photos of what I wanted to protect. To preserve their memory.”

It is in a different mountain where Mejia’s photography career begins. After winning the Global Wetlands Youth Photo Contest at age 20, Mejia was awarded a trip to Patagonia.On his birthday and well into Christmas, he spent six weeks alone carrying a 25 kilogram backpack, cooking his own food, and sleeping in a tent in the glacial peaks at Mount Fitzroy and Torres del Paine. There, mountain lions act on fast, carnivorous instincts, and the weather switches between four seasons each day. “The cold and all the elements — they were something you had to gain inner strength for.”

He admits there were times during the trip when he really wanted to give up. But these challenges helped Mejia realize that photography was his passport to explore the world. “It gave me mobility to meet with my curiosities. It allowed me to be free. But at the same time, it was really spiritual — seeing something so different for the first time alone.”

Photography as relationship

That spirituality comes across in Mejia’s work. In one photo shared on Instagram last May, a devilish gray erupts from the scorched earth of the Agusan Marshlands in Agusan del Sur. The soil and grass are estranged from us, our lands defamiliarized: shot from above, the photo maintains an ambiguous distance between our gaze and the earth. In a video that follows, a forest is nearly destroyed, but the fire is unsatiated — refusing to leave, it relegates to turning the last twigs into ash. In the background, the roosters crow their familiar cry, but their chorus is far more frequent and distressed. Depicting a world where we are alienated from our lands, his accompanying caption to the post reads like an anguished psalm, almost: “Days teeter in the thresholds of polarizing extremes, of fire and flood.”

“Taking photos in that moment, it’s fucking devastating. But you have to bear witness for you to feel the grief, the destruction, the chaos, and the pain that comes from losing lands, losing your culture,” he says.

When I come to a place, I have to meet people eye to eye. I have to build a relationship with the community I’m working with. As a photographer, sometimes I just echo their voices.

As a conservation photographer, much of Mejia’s work is measured by the impact of his visual language to generate change. “It’s my job to visualize and show the truths of this issue: it can be showing the destruction of the super typhoons, or the tenderness a parent gives their child when they’re experiencing torrential rain,” he says. But photojournalism, or capturing how global issues affect people, poses moral questions of its own.

In an essay for The New York Review of Books, Susan Sontag famously writes of the politics of photographing crises. “The person who intervenes cannot record; the person who is recording cannot intervene,” she writes. Decrying the passiveness that photojournalism permits, Sontag argues how photojournalism posits “that any event, once underway, and whatever its moral character, ought to be allowed to complete itself.” Whether depicting how climate change inflicts suffering upon Filipino bodies, or the destruction on Filipino lands and homes, “taking pictures, like sexual voyeurism, is a way of tacitly – often explicitly – encouraging whatever is going on to keep on happening.”

Mejia is careful not to repeat the same actions that Sontag critiques. “When I come to a place, I have to meet people eye to eye,” he says. “I have to build a relationship with the community I’m working with. As a photographer, sometimes I just echo their voices.” For Mejia, photography is more than “just a photograph; it’s about a lived experience” — about real people and the stories they embody.

“Photography, for me, is a relationship but also a vessel. It holds history, myth, identities – all of it,” he says. This focus on relationality draws influence from French photographer and film director Antoine D’Agata, who Mejia once worked with in a workshop in Cambodia. “It’s not how a photographer looks at the world that’s important, it’s their intimate relationship with it,” D’Agata once said. Mejia also believes that photography is “the point where your external and internal worlds collide.” A good photograph requires capturing this in frame, Mejia says, “of two opposing forces within and out of view.”

Then to bear witness to natural calamity through photography requires solidarity and togetherness. After all, what is climate change if not the destruction of our world? In the work of photographing stories for real conservation outcomes, Mejia is just one contributing act – one view of how the global polycrisis affects Filipinos.

Internal landscapes

For the last couple of months, Mejia’s work has focused on conceptual photography, which involves “a more speculative approach to reality,” he says. In contrast to his conservation work, Mejia’s art confronts universal questions of time and space. “With conceptual photography, I’m able to weave more of my internal landscape with imagery” — evolving from passive observer into an actor embedded in the creation process.

Mejia’s ideas of the self are explored in “I’m not here to disturb you, wish you a good dream,” created for the 2023 Angkor Photo Festival, the oldest international photography event in Southeast Asia. The collection featured dreamlike photographs, fusing bright, ethereal hues against a pitch black darkness. In one image, Mejia himself is swimming in a cyan lake. His body is saturated bright pink, and colors the water around him crimson. Only darkness lies before him.

“I came out as gay a month before [the festival], in December 2022,” he says, and creating the collection was a means of catharsis and soul searching. “I had to remove all this trauma, all these internalized ideas of self, of queerness, of reality and fluidity, and show it through the photographs.”

Mejia describes it as a “coming home project.” The motifs and metaphors Mejia employs in the collection envision a journey from dream to reality: photographs first depict ethereal blue rivers and pink-colored trees. Eventually, colors mute and fade, depicting murky and discolored soil, skin, and swamp. Explaining this in the workshop, this arrival at reality signals Mejia’s “acceptance of who [he is].”

Mejia tells me these metaphors were inspired by Cambodia’s built environment – the moats surrounding Angkor Wat where water forms into a ditch to protect the temple against potential attackers. The collection anthropomorphized this landscape, exploring how his internal feelings of fluidity were forced into rigidness. “A convergent point of my external world around me,” he describes, “seeing Cambodia as it is, but at the same time, seeing myself in it.”

Better future through the past

For Mejia, conceptual photography can actually reimagine a more just future for the Philippines. But rather than the high-tech visions of Star Trek or Blade Runner, his imagined future turns away from what lies ahead, and instead looks for “fragments of good in the past.”

In his most recent documentary project, Baradiya, Mejia’s imagined future-of-the-past comes alive. The film narrates the story of Krystahl, an indigenous youth leader as she discovers her spiritual ancestry as a descendant of the Babaylan, Filipino shamans of the country’s pre-colonial era. “From the beginning, Gab’s approach to the project was not just to tell a story, it was mythmaking,” says Miko Reyes, the cinematographer who collaborated with Mejia on the film. “He wanted to revive old myths from [pre-colonization], from when ‘the Filipino’ was at its purest.”

I have to go out there, document the impacts of super typhoons and the effects of wildfires. Because beauty and fragility come from the same coin.

All the events of Baradiya are real, but Reyes says the film differs from traditional documentaries in that its cast acts out scenes, rather than answering questions in an interview. “Gab wants to tell objective stories,” says Reyes. “But then there’s always a touch of magic … a sense of disbelief in how he does it.”

“I see a version of the film where Mejia could have been more objective, where we made a more strict, more rigid, more boring story,” Reyes says. “But he’s just not that person.” For Mejia, there is a radical power unlocked when we relinquish efforts towards totally objective stories, and embrace magic and myth instead. Precisely through fables and futures-of-the-past, we can remember Filipino traditions once forgotten and erased — like how our society “once had queer role models in the Babaylan.” It’s in remembering forgotten histories, in retelling the ways our ancestors lived in harmony with the earth, that Mejia believes we might imagine what a better Philippines looks like.

But what specific future does Mejia want to see? He envisions one that is free from oppression, binaries, and dogmatic worldviews. His thought borrows generously from Caribbean philosopher Édouard Glissant, who coined the term “archipelagic thinking”: a vision of a world “that opens,” where “all the imaginations of the world can meet and understand each other without being dispersed or lost.”

Although the roots of archipelagic thinking are Caribbean, it also feels incredibly Filipino. Our nation, if anything, is an amalgam of our 7,461 islands each with its own unique cultures, histories, myths, and identities. We are one of the most diasporic populations in the world with roughly 10 percent of Filipinos living abroad. Across the country, 183 different languages are alive and spoken, the vast majority of which are indigenous or regional. Heterogeneity, then, is at the core of being Filipino.

And yet it’s hard to see our own country recognize this. Have Filipinos resisted erasure and challenged forces that might universalize it? History might disagree. After centuries of colonialism, Mejia says we have forgotten important aspects of our culture. For him, and the community members who support his work, remembering indigenous traditions is liberation. “We’re all just trying to imagine a more liberated world for our culture as Filipinos,” he says. “A world where we know who we are and we’re self-determined — to be able to actually choose without the influence of global powers.”

Over our final follow-up, Mejia once referred to skyscrapers as “transmuted mountains”: tall cement buildings are, ultimately, gigantic stone structures that elicit feelings of grandiosity.

“It’s all a continuum,” says Mejia. The world he sees is not neatly divided into the natural or the man-made; the individual or the community, or the future and the past. Likewise, in the art he creates, he traverses from dreams to reality, and from the real to the speculative.

Glissant once believed that utopia cannot be discussed with fixed ideas. Mejia does too. “I’m shying away from the language of balance,” says Mejia. And though he might navigate these opposing ideas as an artist, his imagined and impact-driven works converge together in his desire to create meaningful change. “I can’t just live in this imagined world. I have to go out there, document the impacts of super typhoons and the effects of wildfires. Because beauty and fragility come from the same coin.”