The Philippine music industry is often described as “thriving” by major labels that continue to champion talent from key cities in Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. But to some artists living in other parts of a country made up of more than 7,000 islands, that optimism sounds more like a pipe dream.

President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. is set to deliver his fourth State of the Nation Address on July 28 at the Batasang Pambansa Complex in Quezon City. While he’ll focus on the country’s most pressing issues, details on how to boost the country’s creative sector will likely be glossed over. In his last State of the Nation Address, he called for pushing forward an “experiential tourism” that promotes the Philippines’ cultural and creative industries, though he did not provide tangible details on how this would be executed.

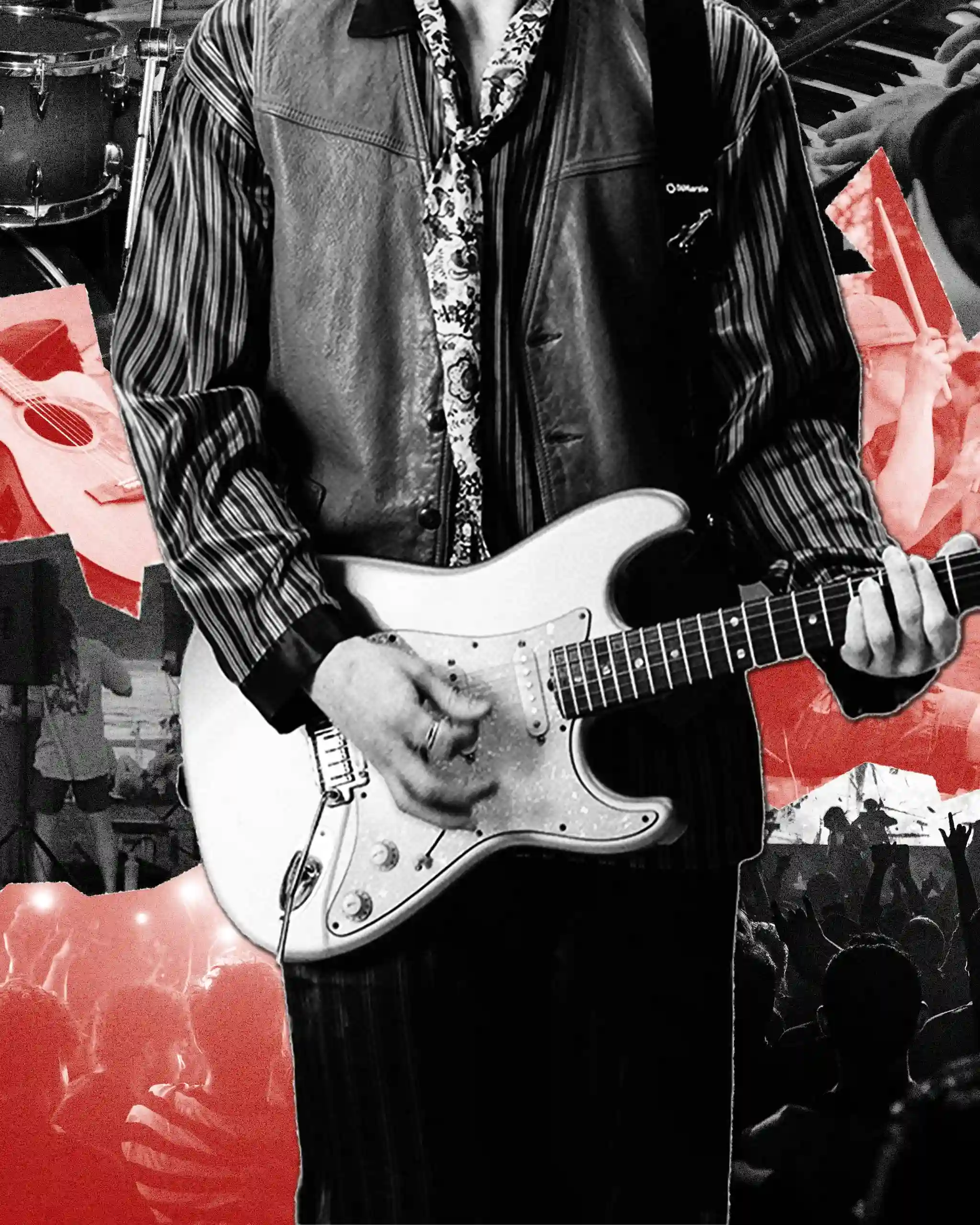

Ahead of SONA 2025, Rolling Stone Philippines sits down with voices from across Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao — artists, label heads, and producers whose work in the independent scene offers a more grounded view of everyday realities of creativity in Philippine music.

Ahmad Tanji, 43, Quezon City

Ahmad Tanji is an independent live music promoter from Shoplifters United, which was founded in 2013, and a lead vocalist of indie pop band We Are Imaginary, founded in 2008. Despite the surge of Filipino talent across genres, many artists still find themselves working within a system that fails to treat music as a legitimate profession. Tanji recalled a moment from Siegfried Barros-Sanchez’s documentary Ang Gitarista Hindi Marunong Magskala where a musician couldn’t even get a bank loan approved after listing “musician” as their job.

The gap between cultural output and institutional support remains one of the biggest structural problems facing local musicians. “If I can throw out a suggestion to lawmakers: Bars and pubs that cater to musicians and artists should be given leeway with reduced taxes or nil, a la religious establishments, to encourage more businesses to open up,” Tanji tells Rolling Stone Philippines. “Think about it. It is a win-win thing in the long run.”

He believes the issue runs deep. The Philippines has no shortage of talent, but the lack of state funding for arts and culture keeps music from becoming a viable long-term career path. Countries like South Korea and Singapore have proven how government support can jumpstart their creative industries. “The Philippines should allot enough budget for the growth and promotion of arts and culture,” he says. “Our country is rich with this manpower, yet it is being ignored. This is an industry that could boom if given the proper platform and funding.”

Virality has also changed how music is made and consumed. “Virality is a disease we can’t shake off anymore,” he says. Platforms like Spotify bring reach, says Tanji, but it also pushes artists to focus more on churning out promotional content rather than the work of creating music. “The positive here is that it reaches more ears, but it makes musicians focus on promotion and content instead of their art,” he says. “Trends kill the growth of artistry and cause a monopoly of style. I mean, pop is pop. But what stands out on the international stage is ingenuity. Filipinos have that, [but] not all can afford to.”

The overreliance on Manila as the hub of everything doesn’t help either. As a musician with roots in Bicol, Tanji is aware of the disparity. Music scenes outside of Manila, like Cebu, Naga, Cagayan De Oro, and Legazpi, continue to flourish despite the lack of government structure and policy, but local artists and organizers can foster space for more music to grow through public incentives.

On the question of indie artists navigating mainstream platforms, Tanji is ambivalent. “I am divided by this concept [of] marketing [as] required in every aspect … I hope this weight won’t fall solely on the artists’ shoulders,” he says. Older musicians or those who aren’t “techy” enough often get left behind. Some initiatives — like those by the Filipino Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers, Inc. (FILSCAP) — offer limited support by licensing copyrighted songs and distributing royalties to registered artists. But enforcement remains weak, and for many Filipino musicians, the system is still impractical. In cases where works are published, royalties are split three ways between the composer, lyricist, and publisher. As a result, many artists prefer direct support from audiences, such as through physical merchandise sold at live shows.

Libya Montes, 40, Cebu City

Libya Montes, founder of Pawn Records and a practicing musician, has remained a fixture in Cebu’s independent music scene since 2001. When asked about the biggest structural issue musicians face today, Montes said it comes down to a lack of genuine support. “Creating more space for genuine musicians would be a good start,” Montes says. But sustainability is another matter: “Here in the Philippines, at least, it’s not very sustainable to be a musician.”

Montes noted that intentions matter too. “You have to ask yourself… Is it for money, or is it for a sense of responsibility?” For those chasing monetary success, he advises keeping your day job: “Maybe there’s a reason why gigs or events happen during the nighttime, so you get to keep doing your job… Being a musician [is] just a sort of release.”

On whether the scene favors virality over longevity, Montes believes the tide has already shifted. “This industry has already become so saturated. You have to have a major backing,” he said. “More often than not, [Filipino artists] give up before they see a semblance of success.”

”The [streaming] platforms benefit from the image of ‘supporting indie.‘ But in reality, they hold all the power at any moment.”

With the VisMin region being so spread out across different islands, Bisaya musicians struggle to find unity in their own scenes, and Montes sees the centralization of Manila as a survival issue. “If you really want to sustain yourself, you have to have live shows. [In Cebu], most of the bands that play in the club don’t pay much.” he says on artists who seek shows in Manila or overseas to earn an income.

On streaming platforms and their relationship with independent artists, Montes is critical. “Most streaming services offer users no financial compensation at all. It’s very unfair to artists who invest significant time and effort,” he says. “They get to take the biggest share of the pie.”

As for who benefits from today’s industry? “I think the smaller artists are most definitely [left behind]… unless you’re really that good and you have a steady fan base.”

Shan Bersalona, 20, Davao City

For many musicians in Davao, including guitarist Shan Bersalona of tuesday trinkets, being in a band isn’t just a passion project; it’s a constant uphill struggle. “The lack of support, fair pay, and long-term career paths means fully accepting that you’re doing this purely out of passion, with very little expectation of financial reward or long-term stability,” Bersalona says, stressing that this struggle isn’t exclusive to Davao, but the entire country.

Most gigs in Davao offer minimal compensation, sometimes as low as P50. “Literal na sakto lang ‘yon pang masahe ko papunta at pa-uwi,” she says. Even worse, some shows offer no pay at all, instead promising “exposure.” Bersalona notes that Suazo, a bar named after its street, stands as one of the few reliable spaces in the city. But even then, compensation relies on door shares. Meanwhile, artists shoulder costs for rehearsals, gear, transport, and day-to-day survival. “There’s so much emotional and financial labor involved, and it’s rarely acknowledged,” the musician adds. This leads many to quit — not from lack of talent, but simply because it’s unsustainable.”

Still, some artists try to build slow, intentional careers outside the pressure of virality. But the industry’s obsession with visibility makes this difficult, Bersalona says. “If your music isn’t trending or getting lots of interactions, it usually goes unrecognized dahil masyado silang kulang sa social media presence. Wala talaga nakakakilala sa kanila.”

Even as indie acts grow online, many rely on platforms that, according to Bersalona, exploit them more than uplift them. “The platforms benefit from the image of ‘supporting indie.’ But in reality, they hold all the power at any moment; your music, your income, your visibility could be gone.” Bersalona suggests this is especially dangerous in an environment where algorithmic trends erase non-conforming voices, including artists who sing in Bisaya.

“What gets lost are the voices that don’t fit the algorithm, there’s always this conservative Filipino thinking na wala namang pera diyan sa art at music na ‘yan,” she says. “And as an artist, you will always find yourself, at some point, thinking that may be true, because huge companies take a huge chunk of benefits that should be going to the artist.”