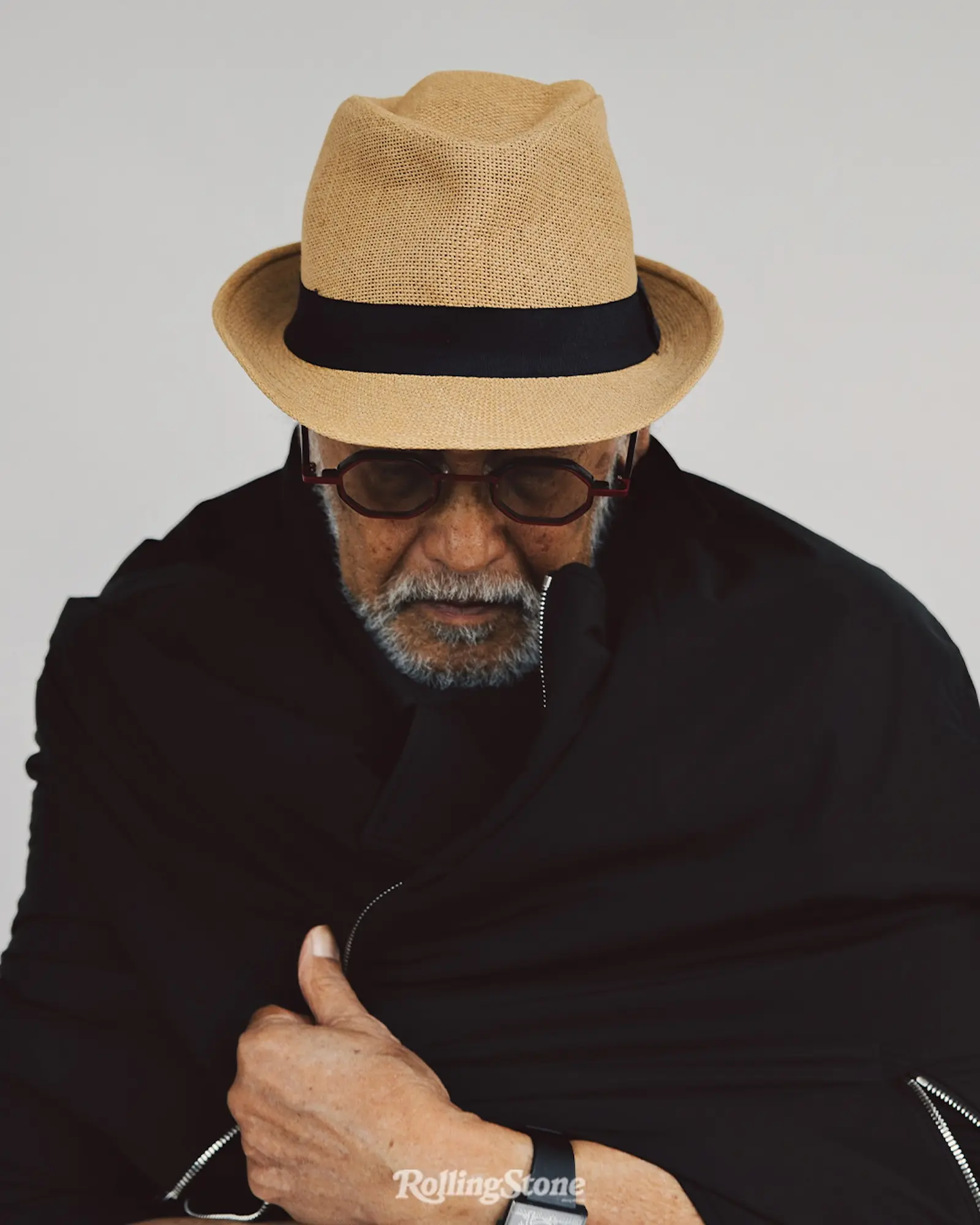

Across his six decades as one of the most acclaimed Filipino artists, Benedicto “BenCab” Cabrera has traveled the world from London to Hawaii, New York to Hong Kong. But it’s Baguio that has become as synonymous with the artist as Sabel, his most famous muse.

Along Asin Road in Benguet, you will find the BenCab Museum. It was built to house Cabrera’s personal collection of Philippine artists’ works — including his own art that he managed to keep for himself or bought back from the original owners. The museum, according to its website, also serves as “a reminder of the rich material culture and traditions of the northern Philippine highlands that have fascinated BenCab since the 1960s.”

Sabel, the artist’s most well-known and most coveted muse, is all over the museum. The legacy (or irony) of Sabel, a muse inspired by a scavenger rummaging through garbage where Cabrera used to live, becoming the artist’s most lucrative work, has inspired many interpretations and analyses, not the least of which is the question of who Sabel, and art, is actually for.

“I have other paintings but all they want is Sabel.”

Still, BenCab is more than Sabel. It can even be argued that his greatest works are those far removed from her. From his sketches capturing the London punk scene to his socio-political artworks in the ‘70s and ‘80s, to his embrace of the arts and culture of the Cordilleras, Cabrera has shown a deep sense of humanity across the vastness of his life’s work.

In a 2005 feature in The New York Times shortly after his four-week residency at the Singapore Tyler Print Institute, Cabrera talked about his decades-long career and how he had grown to move away from social commentary. “When you’re young, you’re more involved, more nationalistic,” said the National Artist. “Now that I’m successful, I’m being realistic… It’s not about selling out. But you tend to compromise more.”

Now 83 years old, Cabrera has referred to this era of his life as his “learning period.” He is at peace in his solitude but does not disconnect from the world around him. He welcomes visitors to his museum and takes photos with them. He is just as happy to talk about the watercress they grow and serve in the museum as he is about his latest sculptures. His museum, while a testament to his work as well as his love of the region, is also his answer to the question of who his art is for. While patrons and affluent collectors fight over his art, the museum stands with open doors for all people to take part.

The following interview has been edited for clarity.

You were part of the first-ever Thirteen Artists Awards in 1970, curated by none other than Roberto Chabet. Could you share what it was like during that time as a young artist? What was the scene like alongside your contemporaries like Raymundo Albano and Eduardo Castrillo?

When the Thirteen Artists Awards were given out in 1970, I wasn’t around as I had already moved to London. It came as a surprise as I was really not part of Bobby Chabet’s clique.

But did you ever get to spend time with Chabet?

We didn’t have much of an interaction as Bobby was more into conceptual art and I used more traditional methods. He did ask me to talk in one of his classes at the University of the Philippines and seemed to be pleased about it.

Could you share how you found yourself moving to London?

When I got my first job, I moved out of my parents’ house in Sta. Cruz and rented a room above Café Los Indios Bravos on Mabini St., which was the hangout then of Malate’s bohemian crowd of artists, writers, and other intellectuals. Nick Joaquin, Virgie Moreno, and other luminaries sat around the center table under a Tiffany lamp and had lively discussions every night.

One night, the owner of the café, Betsy Romualdez Francia, walked in with someone she had met on a boat trip from Hong Kong. It was Caroline Kennedy, a British writer who later became my wife. She looked like a ‘60s hippie wearing a muumuu. Shortly after, she moved in with me, and we decided to travel to London to get married. We traveled through Hong Kong, India, Thailand, and Nepal. It was my first trip abroad.

What was your first show in London like?

Caroline and I lived in a flat in the same building where the British theater actor Henry Woolf also lived. When he learned that I was a painter, he told us that the English actress Glenda Jackson was putting up an art gallery together with her husband Roy Hodges. I was introduced to her, showed her my paintings, which she liked very much, and scheduled me to be the first exhibition in her gallery called The Room.

Film and theater notables like John Schlesinger, the film director, and Harold Pinter, the playwright, attended my opening, and some of them liked my paintings enough to buy them. We didn’t know then that the idea to put up the gallery was to lose money, as the Labor government then was very strict, and Glenda wanted to avoid having to pay high taxes. She was already quite successful then, having won an Oscar for Best Actress. But it didn’t work out because my paintings sold, and even Glenda bought several of my works! So that was an experience, my first show in London.

Did you ever get involved in the cultural scene in London?

Yeah, a little bit, because I got to know a few artists and art galleries. It was good exposure being in London, which has so much history. I visited museums and saw paintings that I had only seen in art books. I got exposed to British art during that period. The ‘70s had minimalist art, but David Hockney and R.B. Kitaj championed figurative art, which was more my style. Both artists influenced my work at the time.

I know [Filipino artist] David Medalla was also in London around the same time. Did you get to spend time with him?

David was in London ahead of me and was known as an enfant terrible. He was still quite young then, but was doing lectures. I was impressed by him as he was very articulate, giving lectures to audiences much older than him. Sometimes we would have dinner together with friends and get along even if we had a different approach to art — he was into installation and performance art while I was used to more conventional methods.

There was a lot going on there in the ‘70s, from socio-economic issues to the rise of punk rock.

Yes, because during that time, the Vietnam War was still going on, and there were a lot of protests that influenced my work. I discovered the punk movement, and they used to hang out in King’s Road, which I found was a good subject to sketch since they were very colorful. I would ask them to come to my studio and pose for me, which they were very willing to do for a small fee.

What about that punk community intrigued and interested you?

They were the wave of counterculture then and had spiked and wildly colored hair, and wore ripped jeans and studded leather jackets. I would invite them to come to my studio in Chelsea and sketch them from life. They would bring their punk rock music while I sketched.

“There are two options open to the Filipino living abroad: one is that his Filipino-ness becomes evident, and the other is he gets eaten up by the dominant culture. In my case, it was the former.”

Did any of the politics of that time influence or inform your work?

Well, I was from [University of the Philippines], and you know, it was already a hotbed of activism even then, so it did influence my political views.

Were you active in politics during your time in UP?

Yes, but I wasn’t as active as other students who were going out in the streets because I had dropped out in my last year of Fine Arts and got employed right away. My first job, funnily enough, was at the USIS [United States Information Service] of the U.S. Embassy. It was ironic because there were protests against the U.S. then, and some of my friends, like the writer and poet activist Joma Sison, were outside the building shouting anti-U.S. slogans while I was working inside, doing layouts for the propaganda arm of the U.S.! I needed a job, you know? I needed to earn some money to support myself.

Did you feel like you could still separate your work from the politics of that time?

Well, I was just a layout artist with the USIS publications, but I didn’t last. Actually, my first show happened because of their support. I had a friend in the U.S. Embassy who proposed that they sponsor my exhibition. That was my first show ever, and it was sponsored by the USIS.

After spending the ‘70s and early ‘80s in London, you came home to Manila. You mentioned that one of the reasons you went home was because of the assassination of Ninoy Aquino in 1983.

I was already quite unhappy living in London at the time, and while vacationing with my family in Majorca, I heard the terrible news that Ninoy had been assassinated. Back in London, my marriage was falling apart, and although I tried to save it, it eventually ended in divorce, and I felt it was time for me to go back to the Philippines, where I belonged. I was missing out on the street protests. I came back in late 1985, in time to participate in the protests that led to the People Power Revolution of 1986.

What was it like for you then as an artist? Looking back, it was during the ‘80s and ‘90s when your work was at its most socially focused.

While living in London, I felt I was more affected by what was happening in the Philippines, watching it from a distance. In 1975, I even produced an etching I called “1081,” the Presidential Proclamation declaring martial law in 1972. I sent some prints to Manila through trusted friends and they were being sold secretly since it was still martial law then. A fellow artist who also lived abroad at that time said, “There are two options open to the Filipino living abroad: one is that his Filipino-ness becomes evident, and the other is he gets eaten up by the dominant culture.” In my case, it was the former.

Read the rest of the story in the Arts and Culture issue of Rolling Stone Philippines. Pre-order a copy on Sari-Sari Shopping, or read the e-magazine now here.