“Are you taking anything tonight?”

Francis, who I just met, asks me. It’s a chilly evening, and we’re at a warehouse in some back alley located between Marikina and Pasig. All roads in Manila lead to EDSA highway, so if you squabble through its narrow side streets, through exhaust fumes, you’ll hear the distantly thumping bass to find tonight’s venue.

Francis, 25, is wearing sunglasses. Partying since he was 14, he turns to nightlife to escape his busy day life. He tells me about some “raves” he’s been to. “Neverland,” he shouts in my ear, “Sonic Garden,” parties I’ve never heard of, yet the names had the same mythical ring as Tomorrowland, considered today as one of the world’s largest dance music festivals in Boom, Belgium.

Tomorrowland, with its land area covering 78 hectares or 145 football fields, is designed to overload the senses. On its 20th anniversary in 2024, Tomorrowland’s intricately designed main stage equipped with a 230-speaker sound system, alluded to the “tree of life” with draping trees, floral embellishments, and bust sculptures carved onto rocky textures that transported tripping partygoers into a surreal fantasy.

Our Manila warehouse setup is far more modest: a few hundred sweaty dancers enveloped by a four-point sound system that, nevertheless, packs a punch. Industrial fans strategically encircle the crowd while Francis, with dilated eyes, scans the strobing dancefloor from behind his sunglasses.

“Is this a rave to you?” I ask him.

“This is more underground than that,” Francis says, pointing at the DJ. “You wouldn’t hear this music there.”

Rave means different things to different people. To some, it is a big party with big crowds and big sound system. To others, it is a subculture rooted in dance music. In 1958, Texan singer-songwriter Buddy Holly recorded a rockabilly track about the thrill of love, “Rave On,” which is to say that “to rave” is also to talk wildly over something. Its Middle English origin, “raven,” means to show signs of madness, while the Old French verb “resver” (like in “rêver”) is to dream.

In London between the ‘50s and ‘60s, young artist types threw hedonistic parties referred to as raves. The sharp-looking mods — like their bohemian predecessors, the beatniks — rejected postwar values of conformity by embracing a fashionable lifestyle that subverted polite society. Mods took speed and partied at raves that played rhythm and blues-inspired rock music.

The 1965 song “My Generation” by The Who, for example, drove anticipation with its pulsating bassline while vocalist Roger Daltrey frustratingly stutters his lyrics as if to tweak from the speed and mumble “fuck” under his breath (“Why don’t you f-fade away? / and d-don’t try dig [sic] what we all s-s- say”). The song climaxes into what was known then as a “rave-up,” a section near the end of a song when the band erupts into a faster, more intense pace.

“The only people for me are the mad ones,” wrote Jack Kerouac, an American writer and key figure of the beatnik movement, in his 1957 novel On The Road. “The ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow Roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes ‘Awww!’”

But in every generation, what is considered “cool” always drifts from the familiar. Take rock music, which, along with rhythm and blues, branched into further obscurity throughout the 1970s. When English football fans from the North traveled down to London to follow their teams, many visited the vinyl store to dig for lesser-known records. A groovy, minimalist strand of punk rock populated the shelves, which many referred to at the time as the “new wave.” Stores also sold funk imports from Chicago and Detroit that, with its uptempo, four-on-the-floor beat from jazz and soul, conjured more athletic forms of dancing in the discotheques (French for a library of phonograph records).

All raves are parties, but not all parties were raves.

In the nightclubs, collectors of these rare records — DJs — were increasingly booked alongside bands, which signaled a growing appreciation for new music, but also a rising hostility. In America, the 1977 film Saturday Night Fever, starring John Travolta, catapulted disco music, largely rooted in black, queer, and Latino communities, into the public consciousness. Many criticized the mechanical and overproduced sound of disco, attributing it to the genre’s commercialization, which included mass produced vinyl records collected by DJs and the widespread use of expensive electronic instruments like synthesizers. As vinyl and disco threatened the cultural relevance of band-based music like rock, a rift grew between the two camps, culminating in 1979 during the Disco Demolition Night clashes, when during a baseball game in Comiskey Park, Chicago, a crate of disco records was blown up in center field, causing a full-fledged riot between attendees and police.

Many consider Disco Demolition Night as the metaphorical moment disco died. Yet Filipinos followed suit with a disco awakening of their own. Bands like VST & Company and Apo Hiking Society helped pioneer the “Manila sound,” a genre of Tagalog-English songs with hooky lyrics and an air of lightheartedness. Take Hotdog’s 1979 hit “Bongga Ka Day” with its bright horns, lush string harmonies, and funky bassline evoking escapism not only on the dancefloor but also from the political turmoil of the martial law years. Meanwhile, folk and rock music were heavily monitored by the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos Sr., with songs like

Freddie Aguilar’s 1979 acoustic rendition of “Bayan Ko” banned from radio airwaves for its political messaging.

Toti Dalmacion, the nephew of Hotdog founders Rene and Dennis Garcia, was a high school student during the peak of his uncles’ band’s success. His aunt, who lived in London, used to bring home cassette tapes of American-British new wave artist Lene Lovich, and Dalmacion collected vinyl records from hardcore punk bands like the Scottish group The Exploited. Over time, he amassed a collection of records that could fit inside a cubbyhole, prompting him to learn how to DJ, which, he tells me, was simply “inevitable.”

In the ‘80s, Dalmacion was an organizer of a “mobile” party called Positive Noise, which played punk and new wave in subdivision clubhouses across Manila, including Corinthian Gardens and Manila Polo Club. Largely attended by students of religious all-girls and all-boys high schools, the Manila mobile parties happened simultaneously with the debaucherous balls of boarding school kids in England, which was a natural evolution of the brick-and-mortar discotheques from the previous generation. “I wasn’t the DJ when I joined. I was just the supplier for the records,” Dalmacion, who is now old enough to be a “young grandpa,” says about Positive Noise, as we sat in a room surrounded by his collection of more than 20,000 records. “I was really into music, so it was very easy for me [to learn] when I was taught.”

In the mid-1980s, Dalmacion’s family moved to Los Angeles, California, where he continued DJing at weddings, a job that is honorable in its egoless approach yet demoralizing for purists forced to deal with a deluge of song requests. But Dalmacion was young and eager to learn. He played crowd pleasers from artists like new wave band Spandau Ballet or the queen of pop Madonna. None of his choices were ever questioned until one day, a shopkeeper at the equipment rental asked about his music. “‘Is it Mickey Mouse dance music or good dance music?’” Dalmacion recalls. “I knew what he meant.” This encounter shifted the mindset of Dalmacion, who, perhaps in an effort to fit in, dug deeper for his music.

By then, he had caught wind of dance tracks that spliced old disco, soul, and funk into electronic loops of drums and synths, tracks you couldn’t even buy on vinyl, but were played at a legendary Chicago club called The Warehouse, which was home to the black, queer, and Latino communities outcasted from disco. The Warehouse sound simply became known as “house” and despite the club’s closure in 1982, house music found home in other places around the world.

“On & On,” released in 1984 by Chicago-based producer Jesse Saunders, is often cited as the first house track ever pressed on vinyl, incorporating glittery and driving samples from Player One’s “Space Invaders” and Lipps Inc.’s “Funkytown.” Chicago artists experimented with synthesizers like the Roland TB-303, a commercial failure that was discontinued in 1984 but was adopted by many house artists for being widely available second-hand for cheap.

The 303’s squelching, resonant bass lines set the foundation for the emergent acid house sound with tracks like Phuture’s 1987 “Acid Tracks” and Sleazy D’s “I’ve Lost Control,” marking house music’s divergence into new styles and territories. By 1988, as Chicago parties faced increasing police crackdowns, acid house became popular in U.K. cities like Manchester and London. Whether this is attributed to British vacationers flying to America or Americans traveling across Europe, where other divergent genres (that could only be labeled in retrospect), like techno, breakbeat, and electro were taking shape, is beside the point. But somewhere along the way, rave reappeared in party discourse to describe psychedelic dance parties attended by thousands of people who, with the help of a little pill, bump, and key, sought respite every weekend.

“A rave, to me, from the way I experienced it, was illegal,” Dalmacion says, referring to licensing restrictions faced by venues and organizers. “It was done in really off-the-wall places like [Los Angeles Union Station], amusement parks. The most common were warehouses.” You could buy a $10 ticket, Dalmacion recounts, and by the time you arrive at the secret location, it’s already busted by the police.

Dalmacion cut his teeth as a DJ in the Los Angeles rave scene. He hoped to introduce it in Manila when he moved back in 1993, so he opened a record store for leftfield music called Groove Nation. To his surprise, there were already parties hosted in warehouses. “But it was such a letdown,” Dalmacion remarks, describing a vast, open space dotted with high cocktail tables. Unlike in Los Angeles, where ravers wore sporty, baggy clothes and chunky jewelry, these events were attended by Manila’s yuppies dressed in uptight polo shirts, chinos, and leather shoes. “I was very idealistic. I came from L.A. where raves [were] for everyone,” says Dalmacion, who felt that partying in Manila was “to see and be seen.”

In ‘90s Manila, the way to a party was through a good old-fashioned flyer handed to you by your man on the street. But new technologies were helping spread information much faster. If you had dial-up internet and a computer, you could log in to chat clients like mIRC and join channels in the Undernet like #gaymanila and #bimanila. If you take the FX (now known as UV Express) at 10 p.m., you can meet your penpal at Giraffe near Glorietta Mall in Makati, then go to the Malate district at midnight, which was the place to be.

Establishments like Cafe Caribana and the Gatsby-esque Penguin Cafe along Remedios Circle attracted the city’s coolest people. In 1995, Dalmacion organized his first Manila rave called Consortium at Blue Cafe, a gay bar along Nakpil Street. But even with Dalmacion’s best intentions, the party was, in his eyes, a “disappointment.” It wasn’t that nobody went — in fact, it was full — but everyone simply stayed outside talking or bobbing their heads and not dancing.

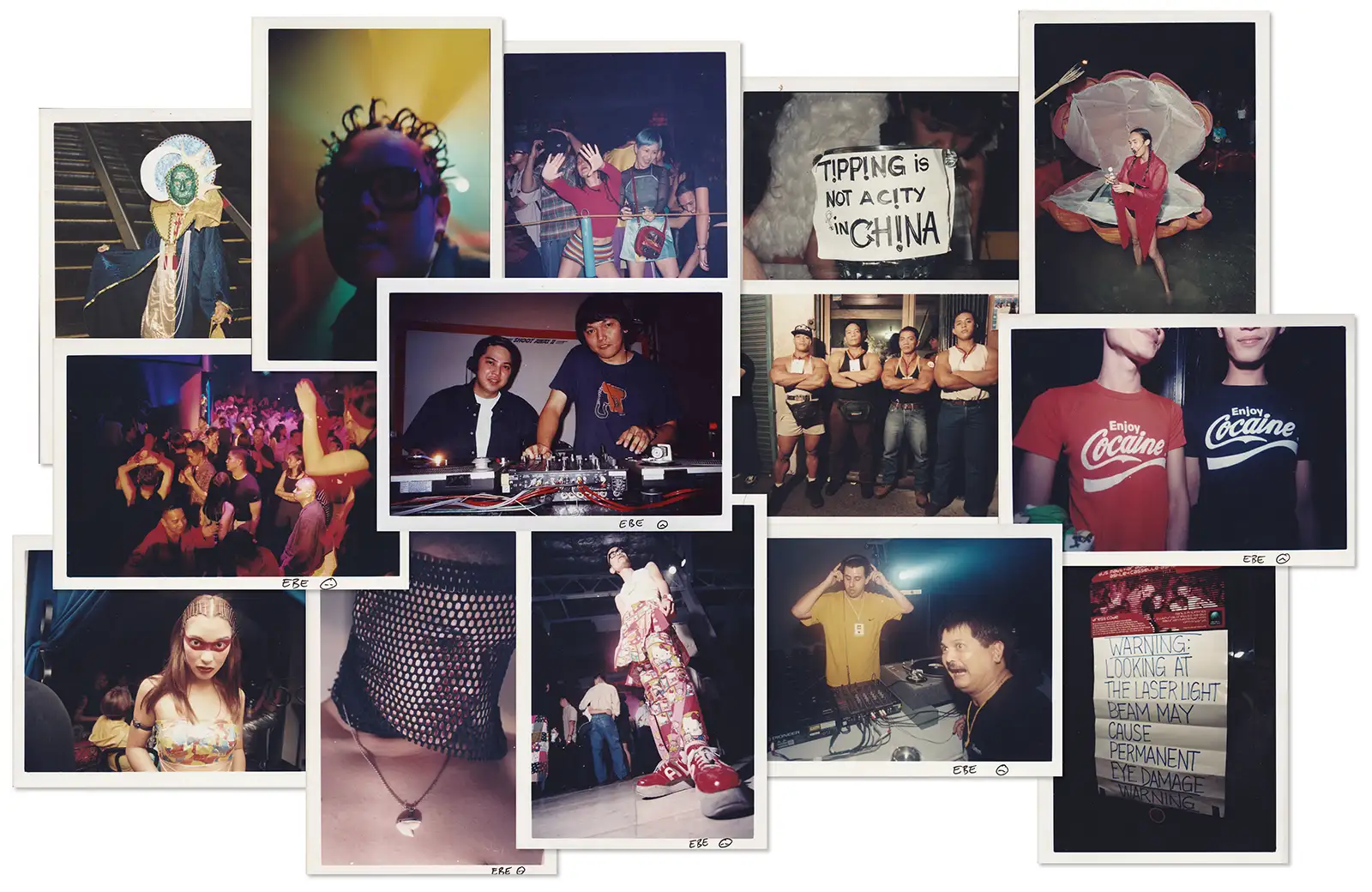

Somehow, it all gelled in 1996 when more of Dalamcion’s friends helped put up the second Consortium at the National Library along Kalaw Avenue, Ermita. Passed off to the library’s administrators as a “cultural thing” (which it was), the party was attended by hundreds of people. There was an inflatable bouncy castle and a video projection of a surgical procedure. Some people were naked, but many, like the goths, aggro-chics, and men in tartan skirts and baby tees, looked incredibly fierce.

Among them was Angelo “Supermodeldiva” Villanueva, who, legend has it, came out of a clamshell dressed as a mermaid at a party. There was also Shora Luna, a muse of Malate’s ‘80s and ‘90s queer culture and the type of creative person who did a bit of everything. Cecile Zamora, known today by her Livejournal blog Chuvaness, was then a fashion designer whose clothes were stocked at Consortium. Even people who have now moved onto high society had a part to play at the raves. Tim Yap, the country’s preeminent “eventologist,” started his career as a promoter handing out flyers. He partied at Consortium while he was a newspaper journalist chronicling the Manila party scene. One night, on the dancefloor, he made a new friend, who was carrying a camera and dozens of film rolls, flailing his arms while completely immersed in the music. That friend was Eddie Boy Escudero, a photographer who later worked closely with Yap in documenting pivotal nightlife moments.

And, of course, there was the music throbbing with bass as airy arpeggios fluttered through the sound system, leaving anyone subject to its spell with no choice but to grab the person beside them and shout, “I love you! We did it!” All raves are parties, but not all parties were raves.

“Rave, to me, was about self-expression,” Yap tells me. “One tribe. No judgment.”

The Consortium crew, a rotating cast of promoters, DJs, production designers, and friends, organized dozens of raves (many of which were free) until their last party in the early 2000s. The new millennium signaled a time when rave dance floors in Europe evolved into massive superclubs, accommodating up to 15,000 people at once. Many of these clubs set up shop in Ibiza, Spain as early as the 1970s, and the island flourished in the ‘80s as a summer destination for British clubbers during the height of U.K. acid house. This gave rise to a Balearic brand of trance music with reverb-drenched progressions that evoke a sunset melting into the sea. Trance is often mistaken for Eurodance, an umbrella term for a similarly melodic yet more operatic and radio-friendly dance music genre from central Europe.

“I hated it,” Dalmacion sneers. “I don’t really care now. But the purists didn’t like it, and I was one of them. Some people couldn’t even distinguish a good trance record, if there was one, from a Eurodance record. That’s why tracks like ‘Better Off Alone’ [by Alice Deejay] and ‘Beachball’ [by Nalin & Kane] were big with everyone because these were all played at the clubs. That was also one of my gripes: why play what everyone else played?”

With each party, you learn something new about that feeling, and how far you can take the fantasy.

I started listening to dance music in 2000 when I was five years old. My brother used to bring home burned CDs of trance music from that one guy in the neighborhood. I eventually learned how to burn my own CDs, downloading MP3s through peer-to-peer networks like Limewire. I carefully followed the releases online, much to the dismay of my mom, who told me to stop spending so much time on the computer. At 11, while on vacation with my family in 2006, I saw a Tower Records flyer advertising a vinyl record signing with Chicago-based DJ and producer Kaskade, whose 2005 “Big Room” mix of his track “Everything” was a staple tune in my household. Meeting an artist whose music I loved reaffirmed my instinctual connection with not just dance music, but the dance itself.

So, imagine my excitement when I finally turned 13, thinking I could pass for 18. The first time I drank alcohol — a bottled concoction of vodka, cognac, and blue fruit juice (also known as Hpnotiq) — was with my mom. My sister and I smoked up in an Amsterdam cafe before I was legally allowed to, and the first time I ever took ecstasy was at a huge convention center in Pasay. I went with my friends, who were older than me, and, to my surprise, ran into my PE teacher, who I often chatted with about trance during recess. Seeing him there so moved by the music gave me a sense of safety on the dance floor, yet I felt that, as a young teenager, I was not supposed to be there — in this space with all these strangers who looked as pleasantly lost as I did. People of older generations have disagreed with me on this — but despite being in such a calculated environment surrounded by corporate logos of alcohol and cigarette sponsors, I considered that night a rave and my first true act of subversion. I went to school the next morning, on the last day before Christmas break, sweating

profusely and running on zero sleep. The inconvenience didn’t matter because I just had the best night of my life.

And much like them, I chased those best nights all throughout my teens and twenties when, unbeknownst to me, dance music was evolving into a global industrial complex. Tomorrowland, with its spectacle of up to 800 DJs and nearly 400,000 attendees from 200 countries, became synonymous with the burgeoning “EDM” scene — a catch-all term for electronic dance music that is notoriously ostentatious. Other festivals like it turned the once-independent dancefloor into a commercial attraction. But I was young and eager to learn. I followed the dance wherever it took me, meeting people who shared this bond. We traded videos of our favorite DJ sets online, longing to party where they did. I wanted to be seen by people just like me. Our dreams became a reality, weekend after weekend. We burned, burned, burned like fabulous yellow Roman candles.

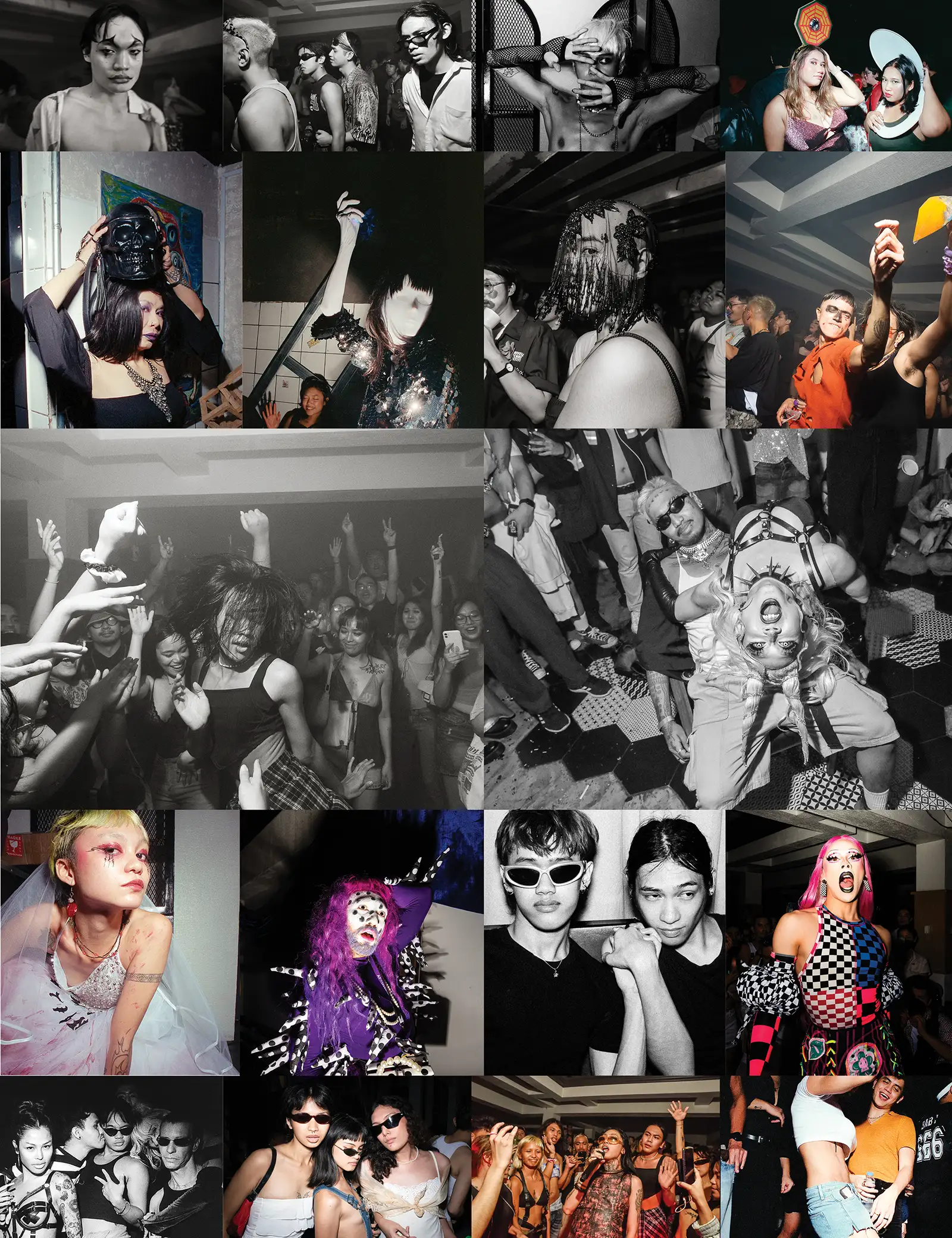

Then the world stopped in 2020. The coronavirus pandemic caused music venues to shut down and the dance music industry pivoted towards virtual parties and live-streamed DJ sets. With so much spare time under lockdown, I threw myself into learning how to DJ, which is unlike any discovery I’ve had with music before. A squelching acid bassline became a marker of time, unearthing a lineage that was connected to my sonic history. My friends and I tested the limits of public conviviality with small spaces and sound systems. People grew braver in the face of the imminent threat to our lives and music was a pressure valve for everyone’s quarantined emotions.

While it was, for a large part, about the music, much of it admittedly wasn’t. Covid restrictions gradually lifted and the numbers game of pulling people to a dancefloor was an act that vied for finite time, money, and attention. Which venue will allow us to make noise late into the night without annoying residents? How much is the sound system? How much are the artist’s fees? How many tickets do we need to sell to break even? And will it be enough to put food on the table, if this is all that’s cut out for me? “Naghalo na ang work at party,” Enrico, a DJ, who is also an organizer, tells me. “It’s great when things go right because working behind the scenes, you get to be a part of creating that fantasy for other people, to share a feeling. With each party, you learn something new about that feeling, and how far you can take the fantasy. So, it feels like you’re not doing your job when it doesn’t live up to the fantasy, which is, in a way, created through the production.”

Rave, as the elusive pursuit of fantasy, has endured as something acted upon and embodied; at times, packaged as a pre-mediated experience. The price we pay for it is the often life-shattering truth that nothing — neither the party, the high, nor the desire in this aging body — lasts forever.

And is that wrong? Because throughout history, entire generations have grappled with their own contradictions where morality was built and broken, the edge of acceptable and even subversive taste was pushed, while everything happened at the same time. “To me, a rave isn’t just a party, but a format,” says Derek Tumala, a visual artist who compares his rave project Kaput to mounting an art exhibition. “The idea of ‘kaput’ is broken, forsaken, or what is wrong. Is it wrong to go to parties? Is it wrong to do drugs? Is it wrong to be gay? That’s what I’m trying to bring into the rave, these ideas of wrongness as something inherent in society.”

Experimentation is still happening and it’s a good time to pick up what you want to see in this culture. If you can’t lend your hand, or join the dance, because the fatigue is in your bones, then you best get out of the way. Because hardcore will never die, but you will.