To be a hardcore punk is more than just listening to loud, distorted music; it means protecting freedom of expression from an establishment that seeks to oppress it.

To be “straight-edge” is an extension of that: a subculture within the hardcore punk community that abstains from alcohol, drugs, and other substances. Being straight-edge signifies a rejection of destructive habits and a commitment to self-discipline.

Choosing veganism takes that a step further. As a stand against the exploitation of animals and broader systems of harm against the environment, it is a commitment that requires a conscious effort every single day.

The punk movement emerged in the late ‘70s from working-class neighborhoods in the U.K., U.S., and Australia with bands like The Clash, Black Flag, and The Saints. Punk music and its faster, more aggressive “hardcore” subgenre later evolved into a global rupture in youth culture that found its way into the Philippines.

In 1981, San Francisco’s Mabuhay Gardens, a Filipino-restaurant-turned-punk-landmark, hosted the first local shows of prominent American punk bands like Dead Kennedys and Circle Jerks. That same year, on the other side of the globe, Manila saw its own entry point into the movement. Staged at the comparatively conservative Philippine Trade Exhibit grounds, the Brave New World concert marked the debut of Chaos, a Filipino punk band led by promoter Tommy Tanchanco, who went on to front the hardcore punk outfit Third World Chaos and the cassette-only label Twisted Red Cross. With a few dozen releases between 1985 and 1989, Twisted Red Cross helped create the blueprint for Filipino hardcore punk music, spotlighting local acts like Dead Ends, Wuds, George Imbecile & The Idiots, Urban Bandits, and Betrayed.

By the 1990s, during the turbulent decade following the martial law years, the local scene had built a grassroots infrastructure that allowed for new musicians to come in. Bands such as Piledriver, Tame the Tikbalang, and Biofeedback kept the sound alive. Small labels like Rare Music Distribution, run by band members of the Philippine Violators, and Middle Finger Records distributed music through independent channels.

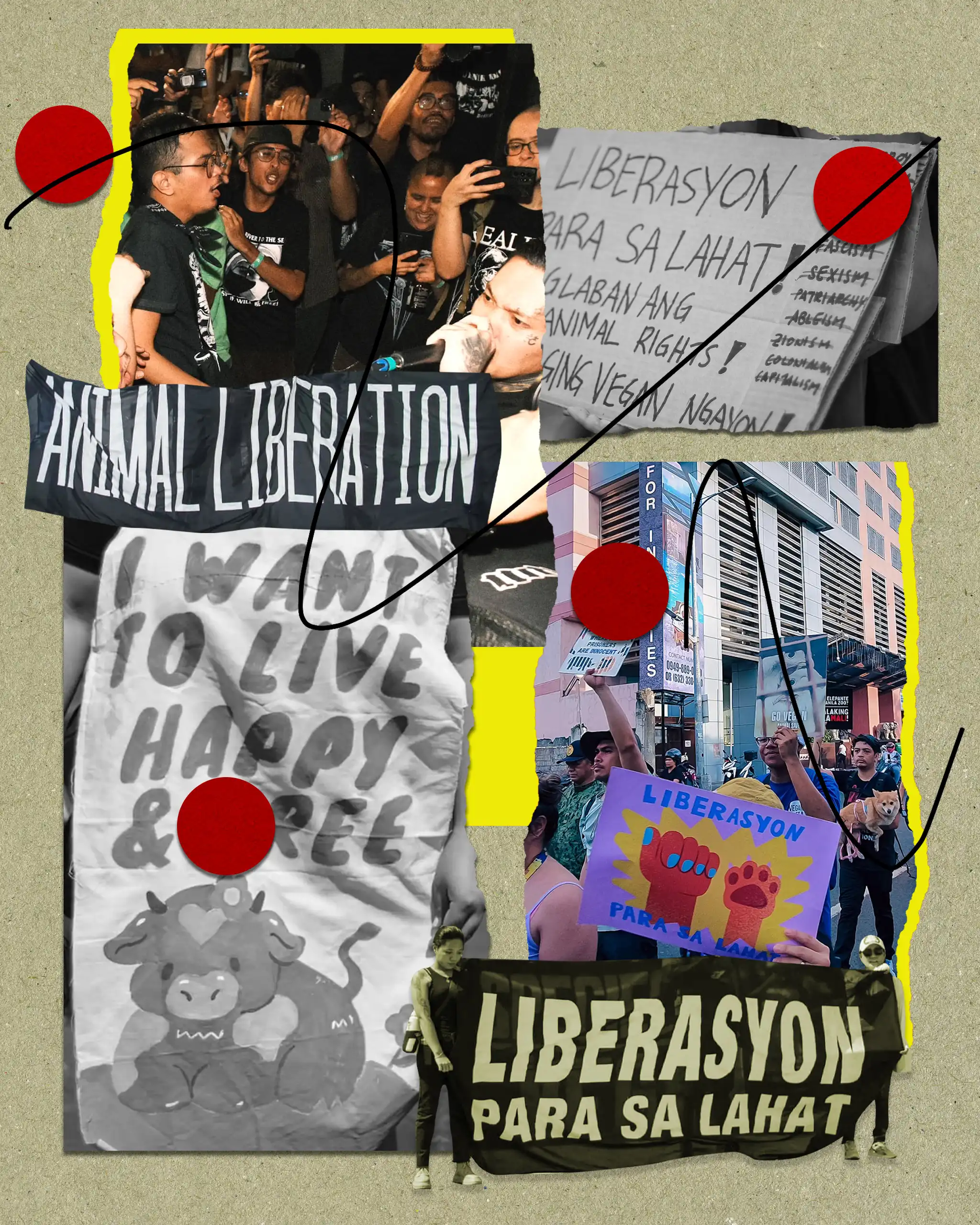

Alongside this wave of activity, ideas tied to the straight-edge and animal rights movement slowly filtered in from the United States and Europe. Hardcore punk was no longer just about sound but about ethics, with sobriety, compassion, and vegan living becoming part of its vocabulary.

Veganism in the Philippines

That connection is where Ralph Espiritu comes in. As the lead vocalist of Gibraltar, Espiritu recalls being introduced to veganism in the early 2010s through Possum X Project, a short-lived hardcore punk band from Zambales. During their shows, the band distributed flyers and DVDs from the animal rights organization People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), exposing the community to disturbing realities of industrial animal production.

“Watching through that whole video with surveillance footage around factories and industrial facilities… The violence is beyond disbelief,” Espiritu tells Rolling Stone Philippines.

For Espiritu, veganism is a natural extension of hardcore punk’s commitment to questioning systems of power as it extends to issues beyond diet. “It’s about avoiding products that harm in any way,” he says. “Pain and suffering of the voiceless — [that’s] something I cannot support. Compassion and [morality] is what persuades me [into] this way of life, to be an advocate for animal rights, and human liberation.”

The concept of speciesism believes that humans are inherently more valuable than other species, which justifies the exploitation of animals for food, labor, and entertainment. Speciesism functions much like racism or sexism, where one group assigns hierarchical dominance over another.

As such, being a vegan in the Philippines is challenging. Filipinos are the 10th highest consumers, 8th largest producers, and 7th largest importers of pork worldwide. Meat production is central to the country’s agricultural economy, and livestock farming provides income for thousands of families. Moreover, a 2022 report by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies states that while the incidence of hunger has declined since the pre-pandemic period, many Filipinos struggle to access nutritious diets: households consume mostly rice and starchy foods, with low intake of fruits and vegetables.

This reality underscores why the choice for Filipinos to become vegan requires not just personal conviction, but also systemic change, especially when advocates are pushing for animal rights in a society that largely relies on animals to survive.

“The visceral nature and imagery of my lyrics do that job for me. If you prioritize digestibility over self-expression, then what’s the point?”

“Exploitation is the root issue [here]. But as someone living in a third-world country, I [recognize] that our agricultural sector is traditionally dependent on animal production, and I painfully understand that [they have] to make ends meet,” he says. “It’s a moral dilemma that, from an animal and human rights standpoint, we may one day figure out.”

Espiritu points out that things are changing, and veganism in the Philippines has become more accessible than it has ever been. A 2025 report by Tokyo-based consumer research agency GMO Foods revealed that 83 percent of Filipino consumers intend to increase their plant-based food consumption in the coming year. Manila Vegans, an advocacy group which, as of the time of writing, has 53,000 members on Facebook, suggesting a growing local interest and a solid community following. For Espiritu, veganism and hardcore punk share a common belief in reimagining systems of survival and how compassion for animals can exist alongside compassion for human communities.

“The consensus [around] hardcore punk [is] anti-capitalism, anti-authoritarianism, and an inclination for social and political change,” he says. “It is [about] resistance at its core. You can’t be right-wing and punk. I can’t say what you should or shouldn’t do. [But] cruelty, in general, is one statement we can all do without.”

Ideas into Action

Gomi is the vocalist of the straight edge metallic hardcore punk band Shockpoint. He recalls how joining Artista ng Rebolusyong Pangkultura (ARPAK), a national democratic mass organization, helped develop his understanding of oppression from within the agricultural sector, and how artists can stand in solidarity with farmers and animal rights advocates.

“We address these issues by communicating [them] through whatever medium we can – be it music, art, zines, benefit shows, you name it,” he says. “It obviously won’t turn everyone vegan, but it gets people talking and asking questions, which is valuable in and of itself.”

Indeed, what makes the vegan hardcore punk movement distinct is its gesture towards the future, using music and art as a vehicle to confront contradictions in the industrial meat economy and demand alternatives outside the machinery of exploitation. As such, honesty is a core value within hardcore punk that, in its goal to convey a message — to treat animals, people, and the environment with equal urgency for care — will never be simplified.

“The visceral nature and imagery of my lyrics do that job for me,” Gomi says. “If you prioritize digestibility over self-expression, then what’s the point?”