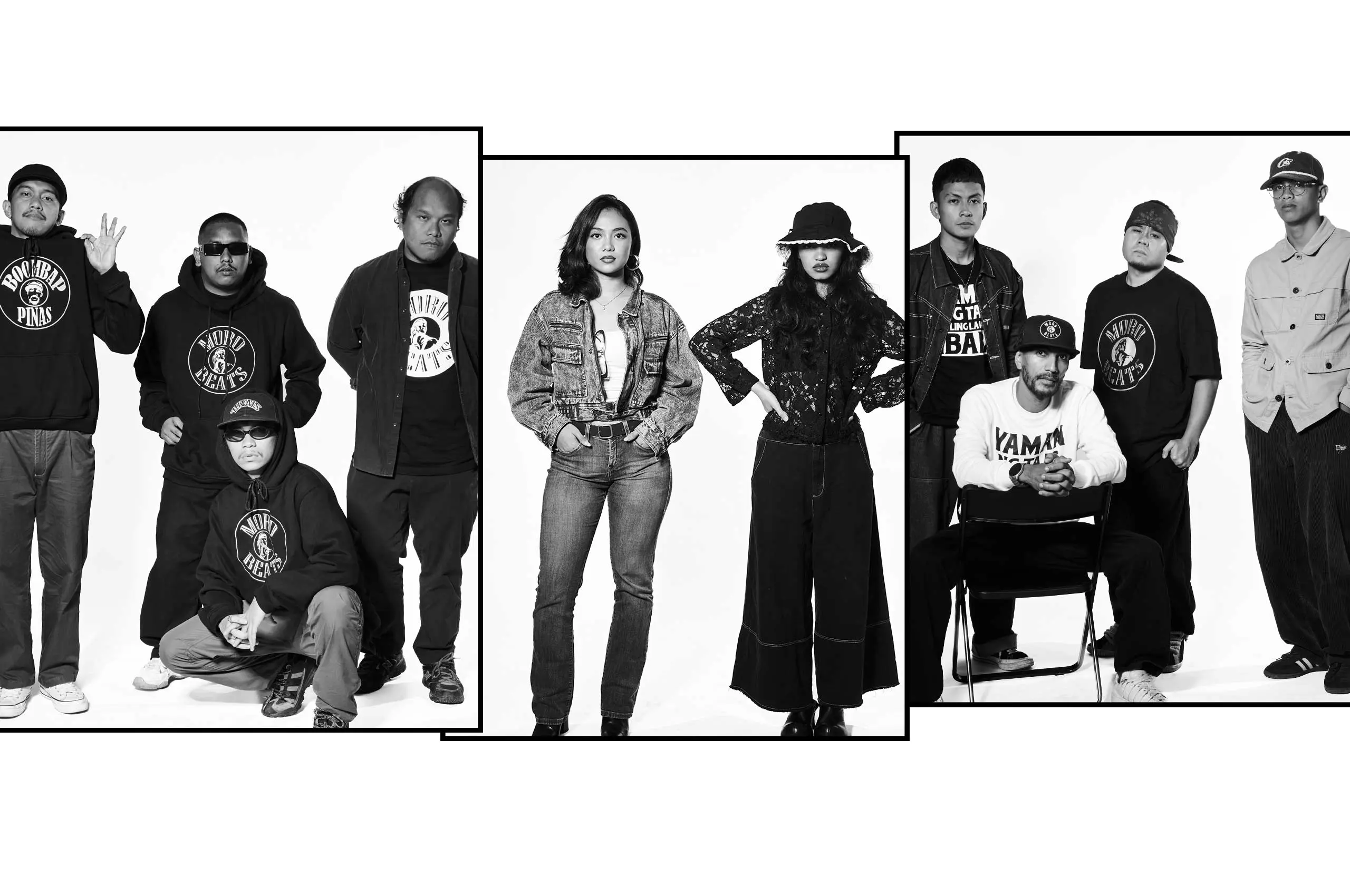

One day, the Mindanaoan-raised rap collective Morobeats gathered at a construction site in broad daylight with anger and pent up rage. With one camera rolling, Dizzy D. of H20 Klann — Morobeats‘ sub-group — plus Morobeats members JMara, Prophecee, Flackos, and Naus stood in the rubble and screamed against stolen wealth, wasted resources, and the arrogance of the one percent.

That moment became the music video for “Anak Ka ng Pu,” their breakout political single that turned frustration into one of the most urgent rap anthems of the year. The single dropped on September 21 in front of thousands of protesters, gathered in Luneta Park as outrage grew over corruption scandals that saw billions of pesos siphoned off to public officials’ pockets while communities continued to drown due to lack of flood control infrastructure. Morobeats tapped into that anger, pulling a thread that connected systemic abuse to the lived experiences of ordinary Filipinos.

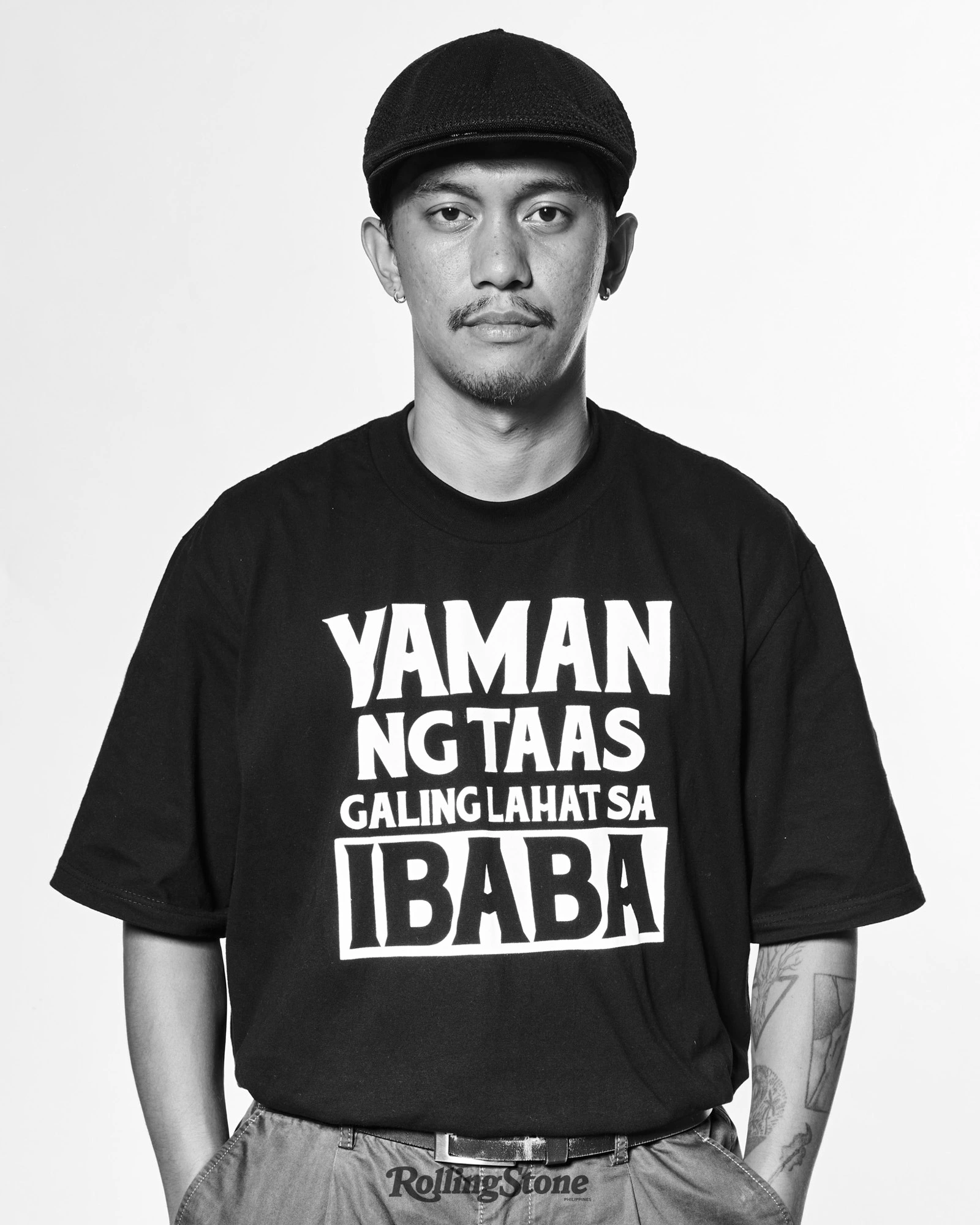

Algerian-born, Zamboanga-raised producer Mohammed Bansil, known in the hip-hop scene as DJ Medmessiah, started Morobeats in 2014 with a private circle of artists wanting to celebrate their dialects and regional sounds. By 2015, Morobeats was no longer an informal gathering; it became a full-fledged collective, and has since grown into a sprawling coalition of voices with one goal: to use hip-hop as a weapon of truth. For Medmessiah, hip-hop was about taking up space for his people and amplifying stories drowned out by silence or stigma. The very name “Moro” carried that weight; historically, it was used as a slur to dehumanize Muslim Filipinos for centuries by the Spanish. By reclaiming it, the collective challenged outsiders’ prejudice, turning their marginalized identity into their own strength.

Medmessiah sat in front of me as he scrolled through video clips from September 21, of how peaceful protests turned into violent dispersals by tear gas and truncheons. He was surrounded by most of the Morobeats crew who, despite juggling their music with day jobs, managed to join us in the studio one morning. As Medmessiah leaned back on his chair, he reflected on the significance of their Luneta Park performance, being in front of a massive crowd on the anniversary of martial law.

“You know, from September 21, mas nagkaroon siya ng mukha, yung mga sinasabi namin,” Medmessiah tells Rolling Stone Philippines, referring to how many hip-hop artists today are preoccupied with songs about flex culture or drugs. “Dati, we were battling [against those concepts]. But [those rappers] are not our enemies. We’re trying to influence them to speak out more about our country.”

‘Boom Bap Kings of Asia’

Before Medmessiah explained what Morobeats meant when they called themselves the “Boom Bap Kings of Asia,” he made sure to clear one thing up: The title was never about ego. Too often, he said, Southeast Asian hip-hop scenes were compared to one another as if they were monolithic. Morobeats wanted to make it clear that boom bap — a style rooted in hard drums and gritty storytelling — thrived most intensely in the Philippines.

“When we say ‘boom bap kings of Asia,’ we didn’t mean na it’s us. What we meant is that the Philippines is [home to] the Boom Bap Kings of Asia,” he says. “Kasi a lot of people are mistaking it na, ‘Oh, why are you claiming that throne?’ Pero we’re claiming it for the country.”

That sense of collective identity is central to Morobeats’ ethos. Individual shine is not dismissed, but it is always folded into a bigger picture. In the writing rooms, discussions often begin with themes like corruption, social issues, or community struggles. As those ideas take shape, members begin to craft lyrics around them. Dizzy D., observes how the collective would go out their way to respond to his emotion, his rhythm, before passing it on to others to complete the narrative.

“Isang bagay din yung pag meron kaming pinag-uusapan na topic [kagaya ng] corruption na doon kami nagkakasundo,” Dizzy D. says. “Bina-brainstorming namin yung topic tapos kami nagsusulat ng lyrics. Pero kadalasan talaga, beat muna yung una. Pag nakakarinig ako ng beat na meron akong certain feeling, naramdaman ko na ako lang ang nakakaintindi.”

When Medmessiah talks about Mindanao, the tone of the entire conversation suddenly shifts. For him, hip-hop also tells the grittier side of human survival. “Mas maraming angst, mas maraming anger, mas maraming emotions kasi yung problema namin sa [Mindanao], hindi lang corruption,” he says. “May kasama pa kaming giyera [at] lack of infrastructure. Kung dito may ghost projects, kami, doon, wala talagang projects.”

“[Baka] meron kang inspiration kahit nasa banyo ka lang, o paglabas mo lang ng bahay, may baha. Kung ‘yon talaga ang nasa puso mo, talagang panindigan mo hanggang sa umabot ng maririnig ka ng tao.”

This history fuels the art of Morobeats, pointing to how places in Mindanao are still barely visible to most Filipinos and how this invisibility shapes the urgency in their verses. They know they carry more dialects, more stories, and more cultural weight than many give them credit for. Their music is a way of forcing recognition, of saying, “We exist, and our problems matter.”

“Isolated ang [Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao] area from Basilan, Tawi-Tawi na ngayon palang nakikita ng tao sa mga vlogs kasi nakakapunta na yung mga tao,” he says. “‘Oh, ganito palang itsura ng Tawi-Tawi or Basilan or Maguindanao.’ Lagi [nalang] kaming huli.”

But one anecdote sticks with me. When Morobeats traveled from their homes to perform at Luneta Park, they compared it to a trip they once took to the West Philippine Sea in solidarity with Akbayan Partylist’s Atin Ito Coalition where local musicians, including singer-songwriter Noel Cabangon, P-pop boy group HORI7ZON, and rock band Rogue, joining seamen to deliver provisions to frontliners. The trip required several days on a boat, and while the logistics of reaching Luneta were simpler by comparison, the symbolism was powerful. “‘Yong Luneta is very easy to go to and ‘yon yung tamang tao, tamang pagkakataon, tamang gathering kung saan namin pwede sabihin yung mga sinasabi namin.”

Survival Strategy

Medmessiah is blunt about what makes today’s hip-hop landscape different. He says collectives like Morobeats no longer have to wait for permission from others to play a show. “Back in the day, [noong] ‘90s and 2000s, we had to wait for this big company to set up an event and hope to be a part of it,” he says. “Ngayon parang, ‘Fuck you guys, we know how to do it.’”

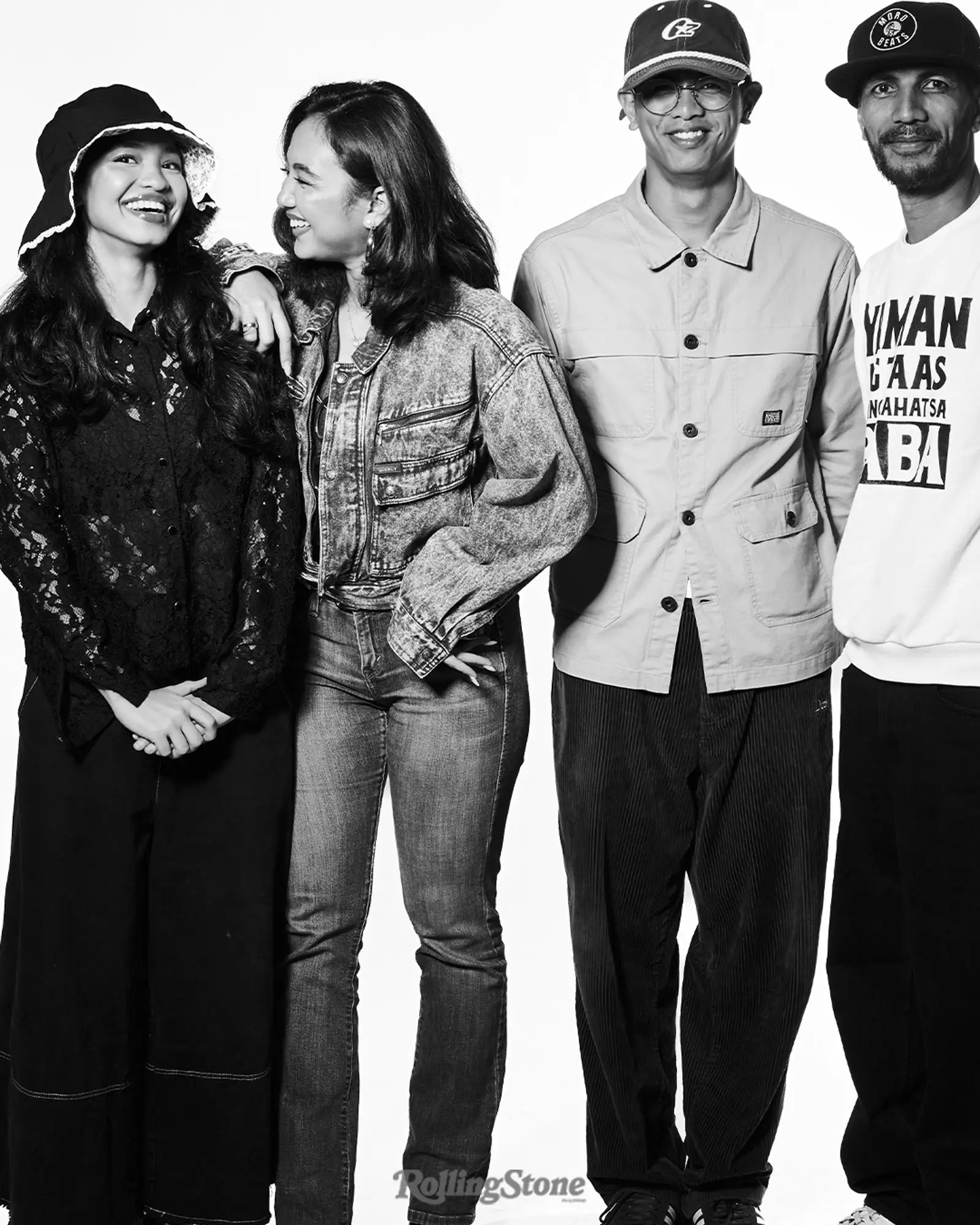

That independence also shields them from tokenism. Medmessiah’s daughters, Miss A and Fateeha, are among the younger voices in the crew. For Miss A, being a female Moro rapper is not about checking a diversity box. “When [young people like us] speak about representation of Moro culture, it’s not like we lack [a sense of] identity. It [shouldn’t be] trendy.” The group’s commitment to relevance is clear in how they choose topics. For Morobeats, there is no single way to package anger. What matters is that the root issues are made visible, and that a new generation sees rap as a tool for expression beyond self-indulgence.

“‘Yong Pilipinas, hindi nauubusan ng problema e,” he says. “[Baka] meron kang inspiration kahit nasa banyo ka lang, o paglabas mo lang ng bahay, may baha. Kung ‘yon talaga ang nasa puso mo, talagang panindigan mo hanggang sa umabot ng maririnig ka ng tao.” This message echoes in everything Morobeats does which — producing, performing, teaching, and mentoring — all of which are acts of survival, and a desire for a better future.

“We’re hoping na kung makita ng maraming tao or maraming kabataan ang ginagawa namin, na yung mga rappers would actually speak out against corruption,” Medmessiah says. “I mean, they can go back to their bitches and and money routine. But sana man lang, once in their lifetime, they would speak out against what’s happening in our country.”