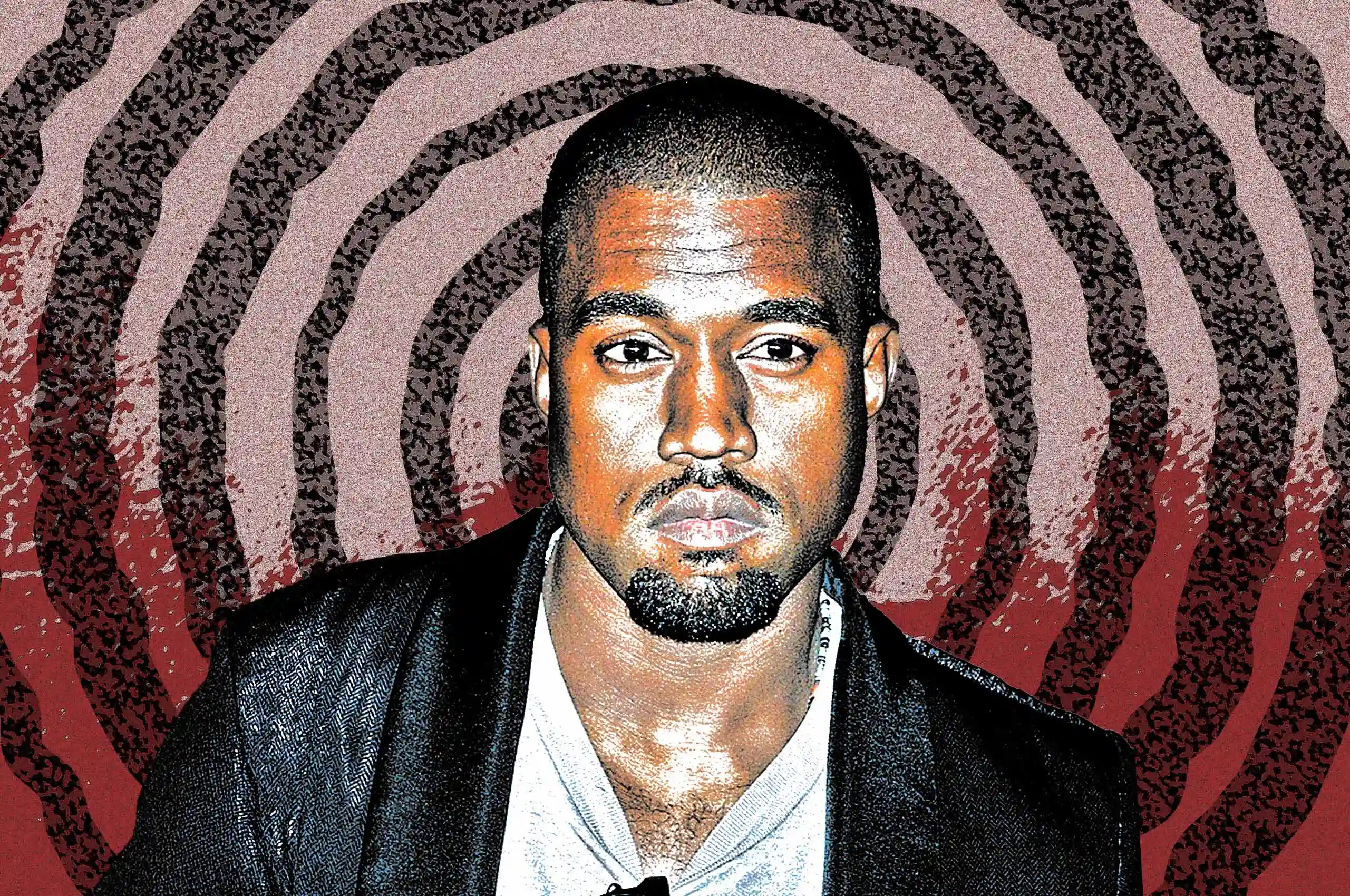

Kanye West, whose name was legally changed to Ye in 2021, persists as one of the most talked-about musicians on the planet, and that’s not exactly a compliment.

According to the 2022 documentary Jeen-Yuhs: A Kanye Trilogy, the death of Ye’s mother, Donda West, in 2007 led to a series of public outbursts as the rapper struggled with his mental health. Whether it’s his periodic dissing of singer-songwriter Taylor Swift, his unhinged MAGA spiels on X, or running a Super Bowl commercial to sell swastika shirts, Ye’s stunts has made any conversation about him so charged that bringing up his name in an interview immediately shifts the energy. Eyes dart while silence lingers.

Still, his impact on music is undeniable. Describing Ye as a “genius” is thrown around way too often, but he might be one of the few who’s truly earned it. Unlike his contemporaries at the time, he was a rapper and producer all at once. Ye’s 2004 debut album The College Dropout saw him rapping with his jaw wired after surviving a car crash, critiquing hip-hop’s decades-old obsession with materialism. His braggadocious rise continued in albums like 808s & Heartbreak, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, and The Life of Pablo, which saw Ye experimenting with maximalist production choices like auto-tune at a time when the music industry saw it as a faux pas. He made gospel relevant again with Sunday Service Choir, a group led by Ye, which turned church music into radio hit bangers. Even his 2024 collaborative single, “Carnival,” with Ty Dolla $ign, Rich the Kid, and Playboi Carti makes it impossible to pretend his reach is fading. His last visit to the Philippines, in 2016 at the Paradise International Music Festival, is still talked about to this day.

The man undeniably shifted the global music landscape. Yet, somehow, the louder the noise gets around him, the quieter his name is spoken.

‘He needs to get a shrink’

“He needs to get a shrink” might come off as a modern-day lyric by Ye, but that’s how one rapper, Ozarugami of rap battle league Kuwagagohan, put it when asked how they feel about the man in question. Finding a Filipino rapper willing to go on record about being a Ye fan is nearly impossible. Most artists I spoke to danced around the topic, wary of not being too forgiving or harsh.

But that doesn’t mean he’s disappeared from playlists. Whether locally or globally, his influence is buried deep in the DNA of modern hip-hop. “I don’t think anyone will straight up say they’re still a [Ye] fan right now,” says Ranviir Bandril, a member of Fresh-ill Club and one of the organizers of the hip-hop collective Career High. “Sa mga nakikita ko rin it’s more of rap fans lang, not really the artists na mas may opinion about him.”

“It’s mostly for the music and the style,” says Justin Wieneke of hip-hop label CHEKE. “I don’t think it’s about being a fan of his behavior or statements.” Some label heads know that fans exist in their circles, but those fans are staying quiet. The artists who once wore their Ye fandom like a badge now treat it like a secret, an admiration tangled in disclaimers. Maybe they’re not cheering him on, but they’re definitely not ignoring him. Bandril believes that most Filipino fans aren’t fussed about the severity of his scandals because of how hard it is to let go of Ye’s music.

“I feel like [Ye’s issues are] more of a Western thing,” Bandril says. “Most rap fans here who are Ye fans either hate what he’s doing now, or still listen to his old stuff but don’t support the new ones.”

Listening Without Loyalty

For those who grew up to Ye in the 2000s and 2010s, their taste was not only shaped by his music, but by all the boundary-pushing things he did, including in fashion and branding. It all felt revolutionary at the time, but Ye’s recklessness today has those same fans figuring out how to separate the music from the man, if that’s even possible.

“I wouldn’t say I’m a fan,” says Ozarugami. “Mas concerned citizen na lang [ako] na nage-enjoy sa music niya, minsan without the thought of idolizing the artist himself. Sobrang out of hand na niya. Hindi mo na maipagtatanggol ‘yong ganon. Kailangan niya talaga ayusin sarili niya. Feel ko talaga mataas ‘yong percentage na ‘yong iba closeted [Ye] fan, habang may maliit na chance ‘yong iba tumiwalag na sa [Ye] cult.” That “cult” may be splintering as fans jump ship to Ye’s public proclamations towards nazism, and his belief that fellow rapper Sean “Diddy” Combs, currently facing trial for sex trafficking and racketeering, is innocent.

Others are taking their support of Ye underground by pirating his music. It sounds absurd, but for many, piracy feels like the only way to keep the art without supporting the artist. No streaming pennies, charts, or public co-signs; just a pair of headphones, private playlists, and a guilty conscience. Ye knows this, too. He’s constantly shifting where his music lives — Tidal on one day, his own website the next — complete with controversial visuals and live streams that tread the fine line between performance art and marketing. Not to mention his latest track “Heil Hitler,” which was taken down from all music streaming platforms — except X, which lives report-free alongside his infamous, stream-of-consciousness tirades.

Filipino rappers aren’t defending him, but they’re not entirely canceling him either. He’s become a ghost in the system, revered in silence and respected through gritted teeth. Though he’s not the face of anything in the Philippines, he is an overhanging shadow, looming over producers, lyricists, and kids in their rooms still sampling 808s because it feels right.

Ye’s relevance isn’t about hype anymore. It’s about history, and history sticks even when the news headlines keep getting worse.