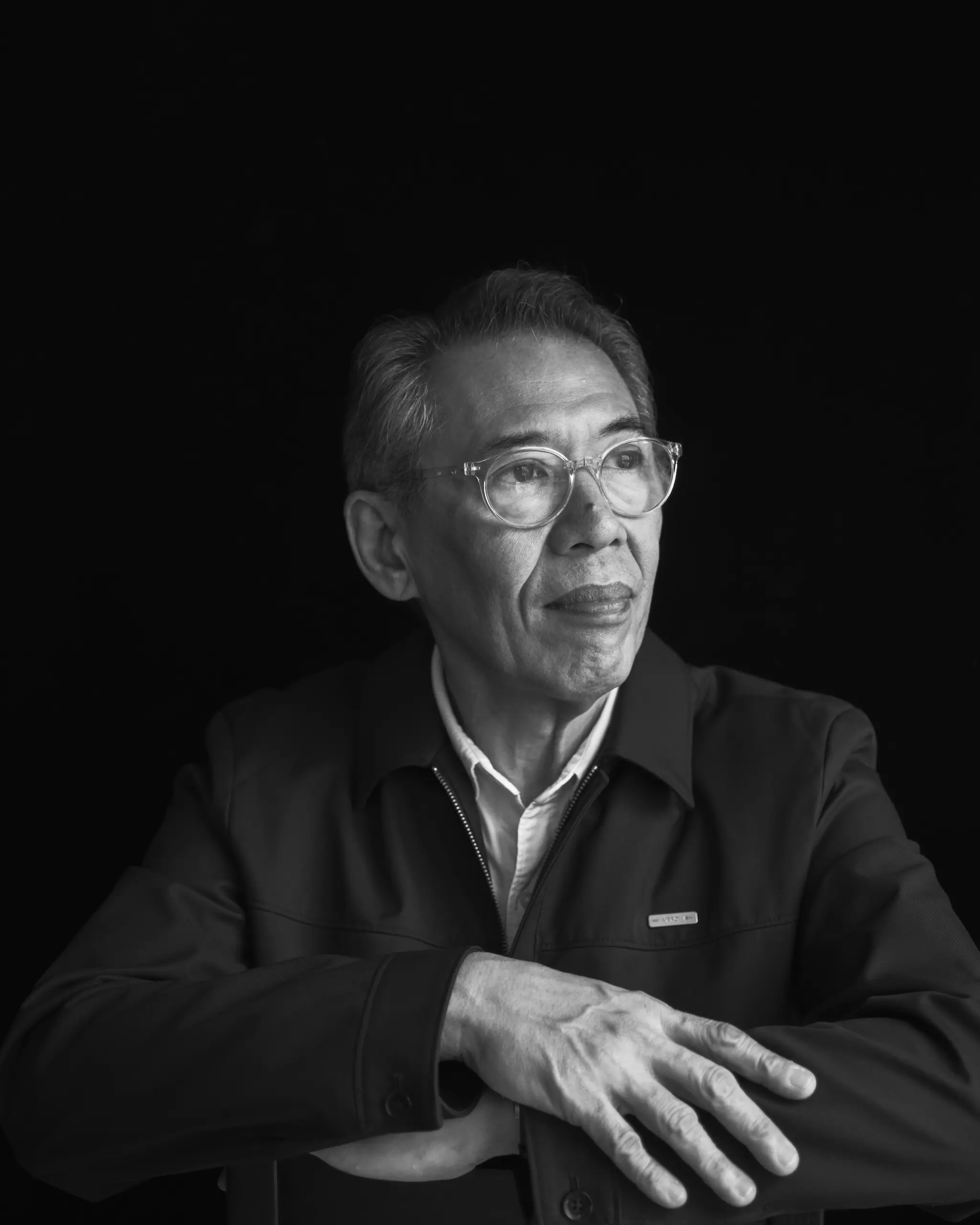

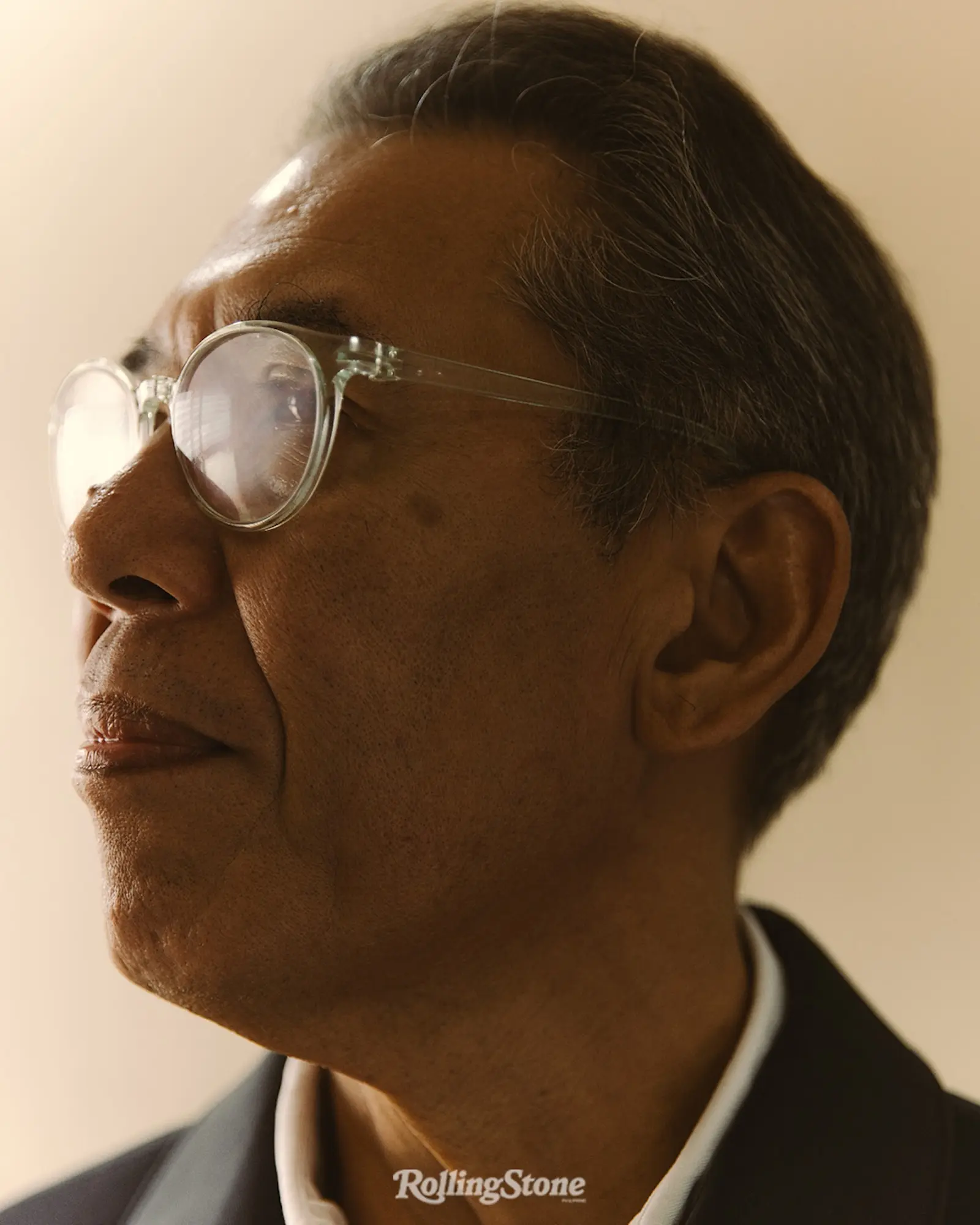

Chel Diokno learned early that responsibility meant being careful with power. In the early 1980s, he watched his father, Jose “Ka Pepe” Diokno, deliver one of those speeches that could still attract a crowd. Ka Pepe has long been a force in public life. A senator and one of martial law’s most unrelenting critics, he was arrested without charges in 1972 and spent nearly two years in solitary confinement. After his release, he didn’t return to politics, but devoted himself to defending the victims of the regime — farmers, journalists, political detainees — using courtrooms, classrooms, and public squares to do what institutions no longer could.

After the rally, father and sons ducked into a café. Outside, the crowd’s charged energy hung in the air. Ka Pepe confided to his sons: “If I had told them to march to Malacañang,” he said, “they would have followed me.” He then added, “I don’t like it.” Diokno understood then that the danger with power was not just possessing it, but how easily it could turn into something absolute.

Four decades and two failed Senate bids later, Diokno is finally a winner. In the 2025 midterms, he ran under the Akbayan party-list, which emerged with one of the highest votes, securing three seats for the progressive bloc. “If you’d told us we’d all make it, that sounds like a nice dream,” he says. He credits the win to Akbayan’s message discipline — “‘Pag mahal mo, Akbayan mo” — but more than that, to the youth. Millennials and Gen Z made up 63 percent of the electorate during this year’s midterm elections. Many had been following him since 2019 when they were too young to vote. But when they finally could, they did.

We have to ensure that progressive and poorer candidates have the same chances of winning future elections as those with a lot of resources.

Where Ka Pepe called on adults to build a nation for the youth, Diokno spoke directly to them. Even outside election cycles, he stayed in conversation with a generation still finding its voice. That consistency earned their trust. His digital presence grew in part through the help of his son, filmmaker Pepe Diokno, who explained, “Our lens was always ‘What can we share?’ instead of ‘What can we do?’ That allows you to talk with people, not at them. To let them in and truly connect.”

His connection to the youth is now a mandate, a kind of power that Diokno knows not to hold too tightly. “I won’t be the first Diokno to step out of line,” he says with conviction. He knows the long game doesn’t end here, and that the real work is just beginning.

In this interview, he revisits the years leading up to 2025, the youth vote that carried his name, and the progressive bloc’s long game in Philippine politics.

You’ve run and lost before. Can you walk us through what those losses taught you as both a candidate and as a person?

I came into the political arena as a newbie who had no prior experience running a campaign. It was a very big adjustment for me. But more than that, it opened my eyes to how power operates in our country, how national candidates have to go down and interact with local politicians to convince them to carry you on their slate. It also opened my eyes to how the playing field is not level at all. If you’re a progressive candidate, dehado ka palagi in terms of resources, donations, and airtime, because airtime is very costly. Moving forward, we have to ensure that progressive and poorer candidates have the same chances of winning future elections as those with a lot of resources.

From a personal perspective, I come from a cloistered background. My events evolved around going to courts and jails, arguing before the Supreme Court, lecturing before lawyers and law students. Mayroon din naman akong exposure sa mga community as a FLAG (Free Legal Assistance Group) lawyer. It was a much smaller world. When I entered politics, it required me to open myself up to new experiences. You interact with people from all walks of life, and doon ko rin nakita na grabe talaga ‘yong inequality in our country and our society. When you speak of poor, it’s not an abstract thing. Millions of people in our country have to live a life of squalor, live hand to mouth.

One other thing which I never expected was the connection I made with the youth. Up to now, it’s still sort of an enigma how that bond has developed. It began in 2019, and I was surprised to receive letters from kids as young as 12 years old saying, “We want to be a human rights lawyer like you. We cannot vote, but we talked to our parents to vote for you.”

Out of curiosity, what made you want to pursue a senate seat as your first rodeo into electoral politics?

It was actually Senator Kiko Pangilinan who first spoke to me about running for the Senate. And at that time, we were in the grips of an administration that was killing without compunction. Where you saw all the freedoms we had fought for being attacked, one by one, as well as the institutions that were supposed to protect our freedoms, [like] the press. You have netizens being arrested and charged with all sorts of crazy cases for simply expressing themselves online. I felt that I couldn’t keep quiet anymore. If I were to criticize these candidates whom I believed were “trapo,” then I have to offer people an alternative. So I wrote a post [on Facebook] about how all these killings should stop, and it was shared a lot. When I was [asked to run in 2018], the first people I talked to were my kids, and they were very open to it. In fact, they were encouraging me to run. And that helped me make my decision.

The minute I wake up, the first thing I think of is “What do I have to accomplish today?” And akala ko umiiksi ‘yong listahan ko, pero hindi, humahaba pa rin e.

You did two Senate bids. While you didn’t get a seat, they built you a profile. This time, however, you ran under a party-list. What changed?

Even entering 2024, I had still decided to run for the Senate. I was going around with Senators Kiko, Bam Aquino, and Risa Hontiveros. I learned so much from them. I was closely watching Sen. Risa’s investigations around that time, and sabi ko, “Wow, bilib na bilib ako.” And that’s sort of what nudged me into thinking about joining Akbayan. At the time, wala pang pagkakataon na magiging nominee ako ng party-list, kasi ‘di pa na proclaim si [Akbayan] Representative Percy Cendaña. It was only just about a week before the filing of the Certificates of Nomination and Acceptance that Cong. Percy was proclaimed. So doon lang nangyari na mayroong opportunity na maging nominee. Kaya mabilisan na desisyon ‘yon. I had to think quickly and make a decision whether to continue my Senate run or to join as Akbayan nominee. I was inspired by Risa’s political journey. Before she won in the Senate, she served twice as a representative in the lower house. I felt it would be the same, whether I become a legislator in the House or the Senate. You’re still going to pass laws.

It is strategic to have allies in both the upper and lower houses. Is this what the party thought about?

Of course, that was one of our hopes. But if you were to tell us last year that Cong. Leila de Lima would make it, that Akbayan would have three seats, that Sen. Kiko and Sen. Bam would make it, we would probably say, “Yeah okay, that’s a nice dream.” We saw it as an uphill battle — and it was. We only realized afterward that certain factors had helped us win. One of them was the fact that in 2022, Gen Z was only about six percent of registered voters. In 2025, they were over 20 percent. That’s roughly from six million to maybe about 18 million [voters]. I don’t think that was captured by the surveys because they don’t survey by age bracket, kaya ang daming nabigla.

And that leads me back to what I was saying earlier, that the young kids who wrote to me in 2019 were only 12 or 13 years old. By 2025, they were already 18 — voting age. Kaya ang tingin ko, ang daming first time voters na nakilahok nitong 2025. Also — and this I cannot give you real data — this is only anecdotal. From what we’ve gathered, many of the youth voted for those they really wanted to vote for. They didn’t fill up all 12 seats, which to me was a very logical thing to do. Because if you fill up 12, in effect, you’re giving votes to those who are competing with the senators that you want to win. Hindi namin narinig iyon noong 2022.

I’m curious: Was there a personal turning point for you, or a moment in the campaign where you felt like the winds were changing in 2025?

I can’t pinpoint any definite time, but we began to sense that the youth were everywhere we went. And it was the same kind of energy and feeling that we felt in 2022. I can’t speak for the other progressive candidates, but the reception I got going around was something else. Plus, the fact that Akbayan has a strong presence on the ground, we were able to enter communities na hindi namin napuntahan masyado previously. Ang masaya din doon, ang kasama ko pagbaba namin, halimbawa, sa Payatas, Tondo, at sa ilang mga urban poor areas sa Laguna and other places, puro kabataan. May kasama pa kaming influencers. And on several occasions, kasama din namin si Sen. Risa. That helped expand our base.

Now that you’ve won, what were the succeeding weeks like for you?

It took a long time for it to sink in. And even now, it’s still sinking in. I don’t feel comfortable when people call me “Cong.” At the same time, ang dami kong iniisip na kailangan gawin. You have to prepare your office. You have to choose your staff. Nandiyan pa ‘yong impeachment. Nandiyan ‘yong legislative agenda na gusto mong ihain ‘pag nagsimula na ‘yong sessions, among so many other things. Right after the elections, I relaxed, maybe for a day or two, and then I started to list everything I had to do. That includes contacting my clients, telling them I cannot appear in their cases, and preparing the necessary documents for that. The minute I wake up, the first thing I think of is “What do I have to accomplish today?” And akala ko umiiksi ‘yong listahan ko, pero hindi, humahaba pa rin e.

Read the rest of the story in The State of Affairs issue of Rolling Stone Philippines. Order a copy on Sari-Sari Shopping, or read the e-magazine now here.