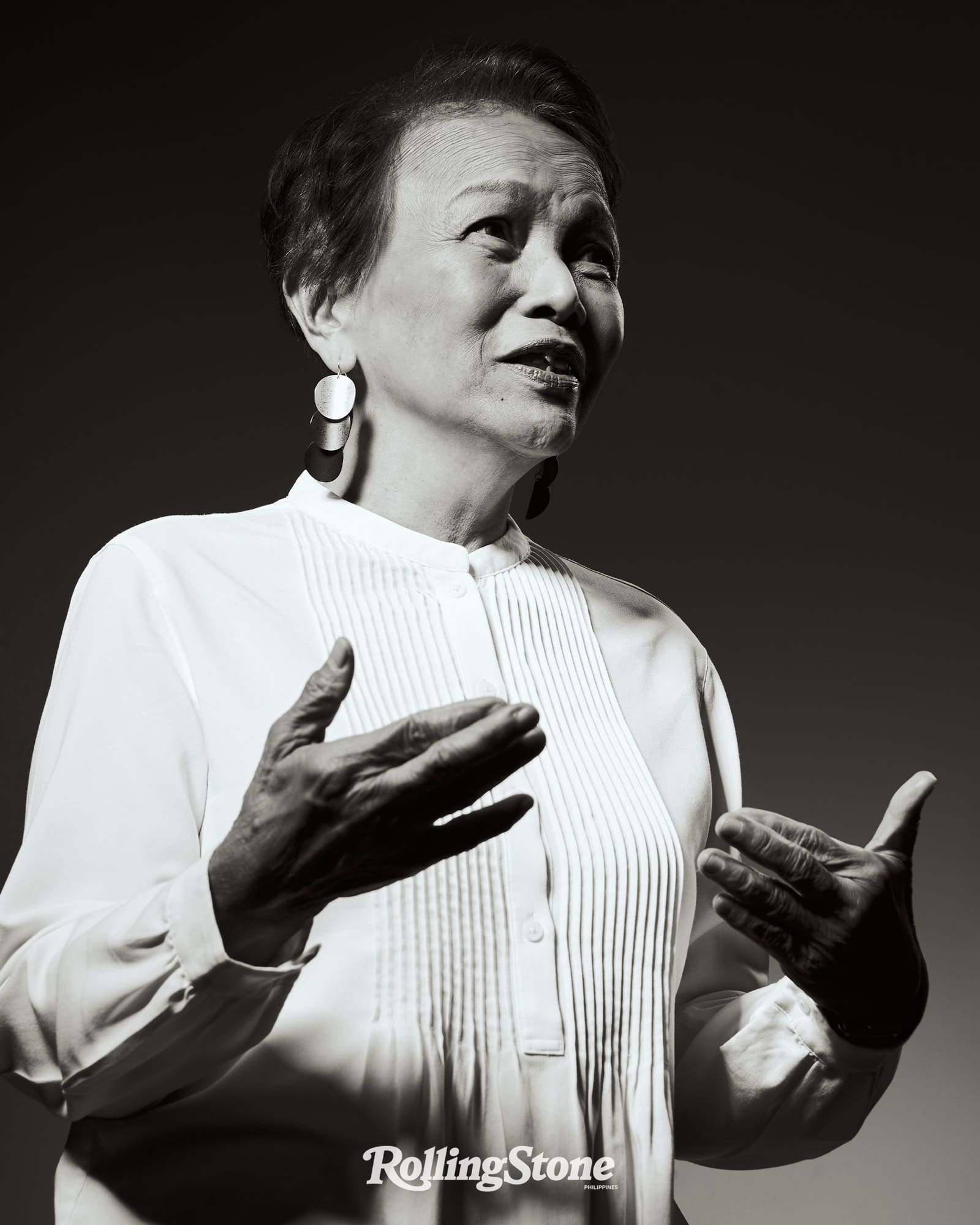

After more than 40 years as a journalist, multiple libel suits against her, and 9 books to her name, including the most recent Unrequited Love: Duterte’s China Embrace co-written by Camille Elemia, Marites Vitug is finally on TikTok. She’s a self-proclaimed baby boomer, who says that she’s on the widely popular social media platform partly because her producer said she needs to reach a wider audience.

“I don’t have my own account,” she says as a disclaimer, while also acknowledging that this is a different age. “It’s not just print anymore; we’re online. So in three minutes, I have to explain an issue, like a foreign policy issue, in our language, which I find challenging.”

Vitug has faced countless challenges throughout her career. She began as a business reporter for the newspaper Business Day, but it is Vitug’s work as a political reporter that cemented her name in journalism. She credits the assassination of the late Senator Benigno S. Aquino Jr. as the catalyst of her shift towards covering politics.

Since then, she has covered two Aquino presidents and two Marcos presidencies. But it is the Duterte administration that is featured front and center in Unrequited Love. Author and political columnist Elfren S. Cruz called the book, “The most comprehensive story of how and why former President Rodrigo Duterte caused a radical change in Philippine policy that led this country to switch from its traditional allies like the United States and aligned itself with China and Russia.”

Vitug talks more about her latest book, the state of journalism, and the ongoing divorce between the Marcos-Duterte UniTeam in this interview with Atom Araullo.

The following interview has been edited for length.

Atom Araullo: Thank you for agreeing to this interview.

Marites Vitug: Thank you for agreeing to talk to me.

Araullo: You are in the unusual position of being the interviewee.

Vitug: Oo, not common.

Araullo: Congratulations on the book, Unrequited Love. For people who haven’t read the book, it’s about Duterte’s pivot to China. What do you think made it appealing for Duterte to focus his attention on China, and vice versa?

Vitug: I think he was looking for a friend who [was] powerful and rich because he [is] very pragmatic. He said from the beginning that he needs China to grow our economy.

He was really comfortable with China as a superpower. When he was Davao Mayor, he received [aid from] China and this continued until Sara Duterte’s term [as mayor]. A school was funded by China. Water systems. He became friends with Chinese from the mainland, Chinese businessmen, and Chinese-Filipino businessmen, [who] supported him in his city projects, [and probably] in his anti-crime campaign.

Araullo: Is [it] a bad thing for Duterte to pivot to China, given the Philippines [is] a developing nation? Would [we] need the partnership and alliances with nations like China, the US, and other “superpowers”?

Vitug: The bad thing was that he excluded the rest of the world: the West. He focused on China. He hated the US. He hated the European Union because they criticized his war on drugs.

Gloria Macapagal Arroyo was the first president to really woo China for investments, mainly in infrastructure. She balanced this with the US. The Philippines joined the Coalition of the Willing when the US invaded Iraq. We eventually pulled out because a Filipino worker was kept hostage and the condition was for us not to support the US.

If you’re a leader of a developing country, you need all possible sources of investments and aid. It would have done the country better if [Dutuerte] tried to balance both and navigate relations between the superpowers rather than staying with one side.

Araullo: Ultimately, do you think his pivot paid off, not just for the country but specifically for the Dutertes?

Vitug: If we look at the pledges of loans, China pledged millions of dollars of loans when Duterte visited in 2016. There’s a long list of projects to be funded. When he stepped down, only three of these projects ended up being funded by China. So if you look at the score in terms of economic benefits, it was not a win-win for the Philippines and China. A dam was funded. Construction is ongoing. Irrigation, it’s done. A bridge connecting Davao to Samal. There were supposed to be railways. My favorite project na hindi natuloy: Safe Philippines, where China was supposed to fund our [information technology] system for improved crime surveillance.

Out of the long list, only a fraction was funded. That’s why it’s “unrequited love” because Duterte gave up some of our sovereign rights, in exchange for only three projects.

But China is still our top trading partner. We export more to China than what they buy from us. In terms of investments, China is not our number one source of foreign investment.

I believe what our late ambassador to China, Jose Chito Santa Romana said, that there should be parallel discussions and negotiations on the economy, trade, investments, and security. We shouldn’t sacrifice our trade, investments, and economy for security. It’s a tough act for a leader to do that. But recently, I saw reports [of] a Philippine trade and investment mission that went to different parts of China. I was glad that we aren’t closing that door. Very pronounced kasi ‘yong policy shift under his administration.

Araullo: Duterte also famously expanded operations of POGOs [Philippine Offshore Gaming Operations] in the country, some of which were later found [to be] a hub for criminal activity. Do you think that was also part of his pivot to China?

Vitug: Actually, Xi Jinping did not want the POGOs here. In fact, he asked Duterte, but Duterte said we needed the income. Looking back as the hearings unfolded in the Senate, I realized that apart from the income that POGOs supposedly brought to the Philippines, didn’t that income go into private pockets as well? There was no paper trail, but the study made by Department of Finance people — I think [former Finance Undersecretary] Cielo Magno eventually made this public — was that the benefits of POGOs to the economy were minimal. It wasn’t worth all the crimes and problems with immigration.

Araullo: Parang mahirap paniwalaan na walang nakinabang, no, na mga pulitiko?

Vitug: Exactly. Because nakinabang in terms of rentals. Overall, the study of the Department of Finance showed that it wasn’t great. In fact, it was the cabinet of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. who recommended that to do away with the POGOs.

Araullo: What do you think about the current controversy that Vice President Sara Duterte is involved in?

Vitug: On the confidential funds. [Sigh] Of course, as journalists and citizens of this chaotic republic, we want accountability. That’s always been our advocacy. We hold public officials to account. There’s a lot of hedging when it comes to releasing information. It’s [about] getting to the bottom of how she spent the confidential funds. But for context, it was Congress who approved her confidential funds [on her] first year as vice president and secretary of education.

Araullo: Is this political persecution? Or is it a rare display of public accountability? Or maybe both?

Vitug: I think it was driven by politics because the UniTeam divorced. So they had to get back. I don’t know if it’s persecution but maybe it’s to get her out of the picture. Maybe in a way, yeah. You go that track of persecution. But at the same time, when my friends and I were talking, somebody said, “This is the good thing that comes out of bad politics.”

Araullo: That’s a good way of putting it.

Vitug: We need to know. There’s an opportunity here for civil society groups, for journalists, to help the public understand this better.

Araullo: Marami na po kayong na-cover na administrations and your focus has been on accountability and transparency. VP Sara has taken a very aggressive and combative approach when it comes to dealing with the accusations. Do you think that is a stroke of genius, or is it the actions of someone who has never experienced this kind of scrutiny in the past?

Our young reporters [are] very good. They’re multimedia. But I think they have to linger a bit and talk to people from whom they can learn, not just rush to the next story.

Vitug: I think for the supporters of the Dutertes, they cannot go wrong. Bebenta pa rin ‘to. Her behavior is still acceptable, and they will not leave the Dutertes just because of this. But for those who are undecided about the Dutertes, or who voted for the opposition before, it really goes to show how alien public scrutiny is [to them].

The Dutertes have been running Davao for decades [without something like this happening to them]. I cannot blame the local media of Davao, because I don’t want to say that, “O kayo, hindi niyo naman kasi ini-scrutinize,” because… you know, the dangers of journalism.

Araullo: Especially in the provinces.

Vitug: That’s why the local governments have to be kept on their toes — not just by the media but by civil society groups. We always have to demand accountability. Maybe [that’s how] they were able to control the local government unit for so long. Nobody asked them the tough questions. That’s why their sense of entitlement has been very strong. It’s now very obvious.

Araullo: Did you expect the spectacular falling out of the Marcos-Duterte alliance this early? We’re only in the second year of their administration.

Vitug: No, I thought they were really in love. [Laughs] But from the beginning, there was no solid basis of unity. Since our politics can be so shallow, I thought they’d survive until the midterms.

Araullo: Same.

Vitug: I didn’t expect it to be this intense. We’re in perilous territory and the state agencies [are] going after her for what she did.

Araullo: Is there a precedent [of this] from the senior Marcos presidency, then Cory Aquino, Fidel Ramos, or Erap Estrada? Do you remember any similar incident?

Vitug: No. Even if there was a falling out, there was a falling out between President Cory and [former Vice President] Salvador Laurel. They disagreed on certain issues but there was no threat [of] physical violence, or threatening to excavate your late father. It was very mild. The disagreements were made public, may tampuhan. But it was only up to that point. I remember Laurel gave a press conference saying why he disagreed with President Cory. That’s all.

But this is the most spectacular, as you say, na grabe talaga.

Araullo: Given that the animosity between the two factions seems to be growing, do you think it will change the attitude of the Marcos administration when it comes to cooperating with the International Criminal Court investigations?

Vitug: They have changed already. In fact, Marcos, from the beginning, said they will not cooperate with the ICC. Eventually, when the split was happening, he said, “We’ll think about it. We may rejoin it.” Now, it’s just “We will not stop the International Crime Police Organization. Rather, we will cooperate with the Interpol, if they come with arrest warrants.” Syempre, we’re clapping our hands.

But others are more cynical. This is a fight between the two biggest political dynasties in the Philippines. Others say it’s time that they destroy each other.

Araullo: Both can be true at the same time, ‘di ba?

Vitug: Correct. This is an opportunity for the opposition to show that there’s an alternative. But that’s another story.

We need to know the “whys” and “hows” of issues — not just the “who,” “where,” and “when.” That’s where investigative journalism really comes in.

Araullo: Isa sa mga na-cover niyo noong nagsisimula pa lang kayo na nag-iwan ng tatak sa inyong journalism ay si former Senator Pepe Diokno. What about him were you most impressed with, and what drew you to his character the most?

Vitug: The context was 1983 and [former President] Ninoy Aquino was assassinated in August. Business Day, my newspaper, was purely a business newspaper. I was so bored covering industries. Then August 21, 1983 happened.

Raul Locsin, our publisher at the time, started a political section. He said we should now cover politics kasi it can no longer be set apart from the economy. We started to cover politics from the parliament of the streets, the opposition, lahat. Then [Diokno] was among the anti-Marcos leaders [who] formed this Justice for Aquino, Justice for All movement. Convenor siya. Wala pang social media noon. I followed him to all his press conferences, his residence to interview him; I went to his meetings with other opposition leaders.

He taught me patriotism in action. I was a rookie reporter — my first ever beat — and I came from the University of the Philippines. I studied a bit of history. For me, he made it alive. It really awakened me, just listening to him. He was so articulate. What’s absent now among many of our politicians is clarity of thought. It was so clear the way he explained, the role of the US, military bases, and the dictatorship of Marcos; how it played into all of this, why Reagan was still supporting Marcos. Wala pang fangirl noon eh…

Araullo: You were the prototype.

Vitug: As a reporter, while writing reports about the opposition, he really gave the story a lot of depth. I went to school with him, in a sense.

Araullo: How do you think governance and politicians have regressed or progressed over the years? If you look at the current crop of politicians, they don’t seem to be cut from the same cloth anymore.

Vitug: There are many theories. But as someone who has covered Sen. Diokno, Senator Jovito Salonga, all these great senators, and then fast forward to today, parang naaawa naman ako sa young reporters.

Araullo: Oo nga. Bakit ganon? Bakit parang baliktad? Hindi ba dapat nag-i-improve tayo?

Vitug: I don’t know if [it’s] the rise of movie stars and celebrities-turned-politicians, or if there will be a time we can go back to having these great people. Not in my generation. Pero the quality of the debates, the conversations… grabe. I mean, Sen. Salonga, we would just sit down and he’d’ just talk about his experiences. As a reporter, I learned a lot from him. I’m just saying this [because] our young reporters [are] very good. They’re multimedia. But I think they have to linger a bit and talk to people from whom they can learn, not just rush to the next story.

Araullo: Now that you mentioned it, do you think, in a way, journalism is to blame for this regression? Are we not doing our jobs well?

Vitug: I don’t want to be harsh on us. No, I don’t think so.

Araullo: Tell us about Newsbreak, which you founded in 2001. What was the idea back then?

Vitug: Actually, the culprits were my friends, Glenda Gloria and Chay Hofileña. They said, “It’s time. Let’s set up a magazine that will do investigative political reporting.” When Estrada was being impeached, they were saying politics was becoming so intense again. Newsbreak was founded just a month before EDSA II. We assembled a small, young team. Our vision was good journalism sells, and we have to make sense of the news. We’d distribute the magazine twice a month. First, we were weekly, then fortnightly. What was most enjoyable was we had time to really go into the behind-the-scenes of breaking news. We didn’t have to do daily reporting.

Araullo: Do you think that format is lacking in the current age of journalism and social media, where everything is so fast?

Vitug: Yeah, and I think that’s why in Rappler, there’s an investigative team. News media outlets also have teams that do in-depth stories. We need more of those.

Araullo: Oo. Pero hindi kumikita, ma’am, e.

Vitug: Oo nga, and it takes a lot of time to do it. You spend so much then you don’t earn. That’s why you have to do it.

Araullo: You’ve faced libel charges because of your brave work on the judiciary. What was that experience like?

Vitug: I’m not yet libel-free. My first [libel charge] was a bit traumatic. This was before Newsbreak. I was a freelance journalist and I co-wrote a story on the plunder of Palawan’s forests for the Far Eastern Economic Review. The bureau chief and I were both sued, but he was away so I was the one left holding the bag. That was the most expensive libel suit at the time: P20 million.

Araullo: Were you exonerated?

Vitug: Yeah, and I’m glad the Far Eastern Economic Review editor-in-chief flew from Hong Kong, met with me, and assured me.

Araullo: You were probably a very young reporter at the time.

Vitug: Yes, and I was assured of a lawyer’s help. So, eventually, it got dismissed.

Araullo: I can’t imagine going through all of that. Do you consider that a badge of honor?

Vitug: No. It’s something that makes you lose sleep. It cuts into our meager resources. Of course, we have lawyers na pro bono but it was really a hassle. I learned a lot. I learned to be very careful.

Araullo: I assume you’re against the criminalization of libel.

Vitug: I don’t want it to be a criminal offense. In fact, the Supreme Court recently told the courts in a decision that they can fine but they don’t need to impose a prison sentence. They can also fine the news outlet.

But sometimes, a single fine can bankrupt a news media outfit.

Araullo: It sounds to me like that threat is always hanging over the head of any young intrepid reporter who wants to document something important.

Vitug: That’s why it’s very very important to keep your notes. Lesson ko ‘yan. Keep your notes. Be very careful. Double-check always.

Araullo: Make sure your ass is covered at all times.

Vitug: Correct.

I was reporting within the bounds of fairness and accuracy but with a goal to expose things so we will move on to a democracy.

Araullo: I want to talk about the state of journalism today because it’s evolving at a dizzying pace. Even for somebody who is relatively younger, it’s hard to keep up. We’re not just talking about social media we’re also dealing with artificial intelligence. As a veteran, what do you make of the current state of journalism in the Philippines, and maybe even globally?

Vitug: I’m hopeful when I meet young journalists who are really hardworking, promising, and idealistic. When I meet them, I think, “There’s hope!” [Because] we get jaded. In our field, there are the bad eggs — those who make corruption sound normal in journalism.

I admire the versatility you can do on many platforms. You can reach a lot more audiences than before. Journalists like me face new challenges. At the same time, it has become a double-edged sword [because of] disinformation. A lot of social media feeds, you have to fact-check. It’s a mixed blessing. For me, we have to stick to the old-fashioned rules: Accuracy, fairness, honesty in reporting — whatever medium, whatever platform we’re working in. There’s a lot of talk about AI. I’m new to this, and I use AI grudgingly.

Araullo: It’s mindblowing.

Vitug: Again, it’s a double-edged sword. It can be used as a tool, and it also can be used to destroy our values, even our sense of what’s right and wrong — these deepfakes, and all that.

Araullo: The way we consume information nowadays is so different from 10 years ago. Do you still watch TV?

Vitug: I don’t. I used to watch the evening news. It’s all YouTube, it’s all social media now.

I still read the newspaper. For the record, I have it in the morning. But sometimes, after one week, nandoon pa unread. But I review kasi baka I missed something.

Araullo: [For] people like us who work in the news, it’s [already] hard to keep up with current events. Imagine a regular working-class person. How do they make sense of what’s going on around them? Their gateways are people on TikTok, ‘yong mga influencers [at] viral posts, which may or may not be true.

Vitug: That’s why we have to compete. You’re not on TikTok?

Araullo: No.

Vitug: But you have to compete, ‘di ba? That’s what I was told.

Araullo: Or maybe not compete. You have to offer an alternative.

Vitug: Yes, or maybe give more information. So I hear some of— well, my brother’s driver [listens] to all these vloggers na propagandists. I had to tell him, “Uy, dahan-dahan lang diyan kasi ‘di totoo ‘yong mga sinasabi niya.”

Araullo: What concerns you the most?

Vitug: Journalists need to be more prepared and ask the tough questions. I watched the presscon of Vice President Sara and parang sayang. I know the journalists cover her, they know the issues. But maybe because they’re too close to it, they fail to follow up, or they fail to ask tougher, bigger, contextual questions. That’s when the editors should come in.

Araullo: Going back to your expertise in investigative reporting and in-depth reporting, what role does it play in society and in a democracy like the Philippines? Do you think investigative reporting still has a place with all these different content creators?

Vitug: Yes, it has. But it’s really difficult to sustain it.

Araullo: Why do we need it?

Vitug: Because we need to know the “whys” and “hows” of issues — not just the “who,” “where,” and “when.” That’s where investigative journalism really comes in. Maybe it can be shorter, but the key questions should still be answered.

We have to stick to the old-fashioned rules: Accuracy, fairness, honesty in reporting — whatever medium, whatever platform we’re working in.

Araullo: What is your message to the younger generation of journalists who have a big role to play in the next decades and, hopefully, are in this for the long haul?

Vitug: Those who aspire to be journalists should always be interested in events, people, and the world outside you. Be curious. Then, you’ll graduate into being passionate about it then into being somebody who wants change — change for the country. You grow into it because you experience different layers of purpose.

When I was a young reporter, I just wanted to report. But when Aquino was assassinated and we wanted the dictatorship to go, it had a purpose. I was reporting within the bounds of fairness and accuracy but with a goal to expose things so we will move on to a democracy. Now, we have a democracy, and we have a goal to deepen this democracy — but still within a non-partisan way of reporting. It’s really a lifelong journey.

Hair and makeup DOROTHY MAMALIO