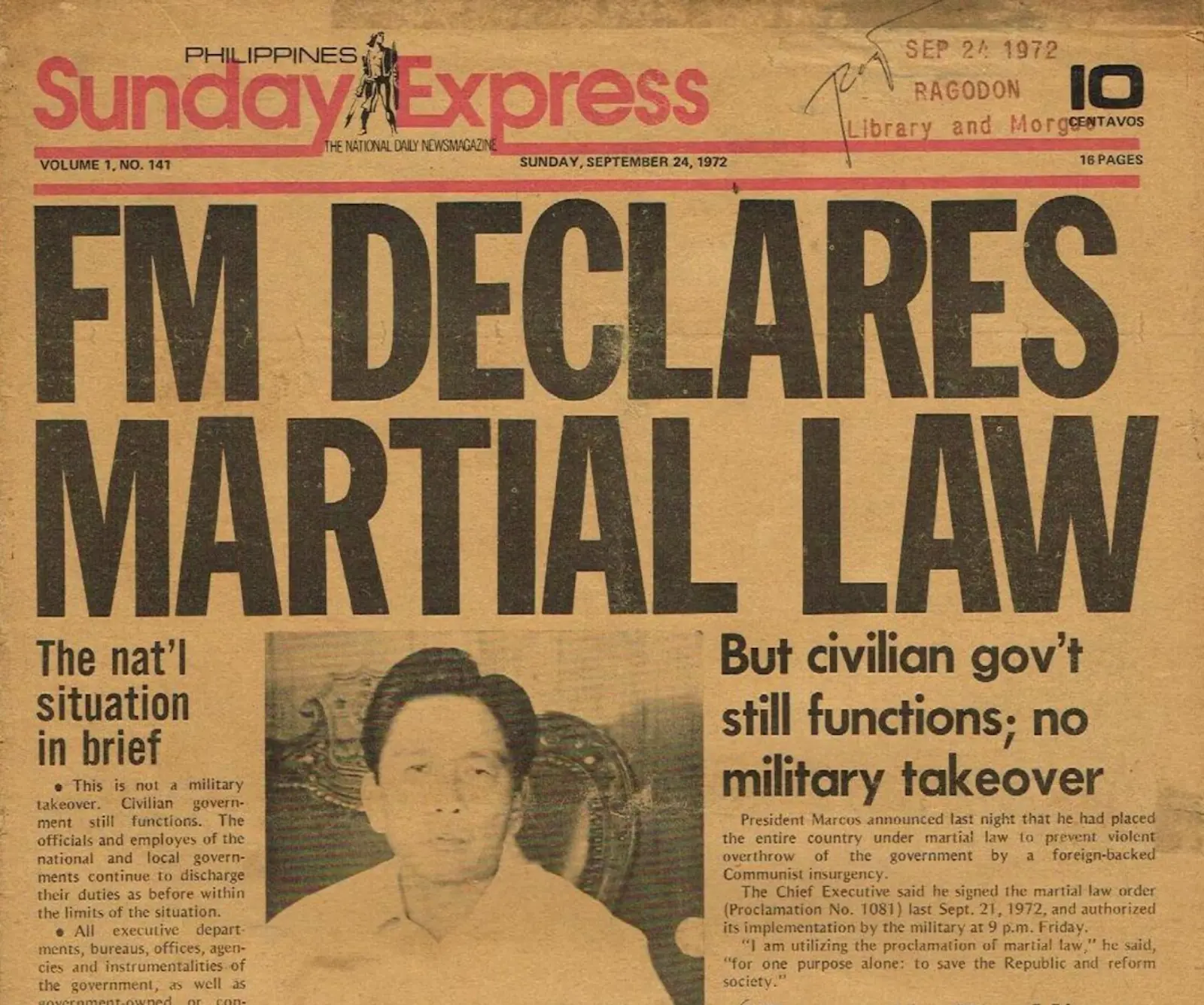

Teaching martial law is a tricky thing. Educators have long struggled with potholed syllabi, rigid educational institutions, and their own personal beliefs when it comes to teaching students exactly what happened when former president Ferdinand Marcos Sr. declared martial law in 1972.

Although the Department of Education (DepEd) does include martial law in its nationwide curriculum, the government agency has also been criticized for not providing a holistic enough picture. In 2023, DepEd came under fire when, as part of the new “Matatag” curriculum, the dictator’s name was removed from the term “Diktadurang Marcos” in the Grade 6 Araling Panlipunan program. “This revision by DepEd is a clear strategy of the current administration to rehabilitate the dark history of the Marcos family,” the Congress of Teachers/Educators for Nationalism and Democracy wrote in an official statement denouncing the change.

View this post on InstagramAdvertisement

For Rhoderick John Abellanosa, an educator at the Ateneo de Cebu and current coordinator of the school’s Research and Impact Assessment Office, the textbooks at his disposal continue to provide a fragmented view of martial law. “There was a journal article released years ago that showed that books on martial law reduce [it] to a caricature,” Abellanosa told Rolling Stone Philippines. “Nothing much is said about the actual number of human rights violations. No description of the tortures. There’s an emphasis on the need for peace and order during that time, but not much is said about Marcos’ desire to stay in power beyond the limits imposed on him.”

Abellanosa, who has taught students across grade school, junior high, and senior high, noted how external factors — particularly a school’s own biases — can impact the teaching of martial law. “When martial law is given emphasis in schools… half of it is in part due to how lessons are structured based on the DepEd’s curriculum,” said Abellanosa,” but the other half of it is the prevailing intellectual climate or the political attitude of the people at the school. That’s a major contributing factor, and that’s where the subjectivity comes in.”

“We need to be objective and accurate,” continued Abellanosa. “If, for example, 500 people died, then it must be 500: we should not say only 200 died, or debate on whether it was 200 or 400. Or if [people] were killed because of military abuse, we should not say that they were killed because it was also their fault. We twist, but that should not be [the case]. That’s inaccurate.”

For other educators, the issue also lies in the limited amount of time to teach the subject, especially to a cohort of young students who did not experience martial law firsthand.

“Educators play a big role in determining how martial law is taught. However, we always show only one side of it.”

“By the time the school year ends, parang hindi pa umabot ang martial law,” Dr. Jose Victor Torres, a full professor at the History Department of the De La Salle University-Manila, told Rolling Stone Philippines. “What happens is it ends up being touched for maybe one, two meetings. In my case, I show my students Batas Militar [a 1997 documentary about martial law], but I’m sure that some of my undergraduates view it as an assigned viewing, and that’s it. Did they learn much?”

“And it’s also an entirely new generation,” continued Torres. “I had a student ask me, ‘Sir, what happened during martial law?’ I told [them] na there was torture, illegal arrests, and executions… You know what that student told me? ‘So hindi ba nangyayari pa rin ngayon?’ How do I answer a student who asks something like that? That’s why I think it’s so hard to teach martial law… because the things that happened then are still happening today. And students don’t see any difference.”

What to Take Away

Both Abellanosa and Torres emphasize that learning about martial law is more crucial now than ever before, especially in the context of the current Marcos administration, the rising cases of corruption scandals, and a nationwide distrust towards those in power.

“It seems that we are ko a people na… murag natagak [as if we’ve fallen] sa mud, noh? And we don’t have the capacity to pull ourselves out from it.”

“Educators play a big role in determining how martial law is taught. However, we always show only one side of it,” said Torres. The professor continued by noting that, although many educators have tried to highlight the personal experiences of martial law victims, this may not be the most objective or accurate approach to teaching it. “I’m reminded of that phrase, ‘in order to fight your enemy, you should know what your enemy is like,’” said Torres. “We cannot learn anything about martial law unless we know the entire story.”

For Abellanosa, it is up to teachers and educational institutions to rise to the occasion. “The influence of teachers really goes a long way, if only we use that position with integrity,” said Abellanosa. “But I think this is where educational institutions have failed: we haven’t used that influence. We are getting more and more concerned with our social reputation, how we brand ourselves, and so we would prefer not to run into any trouble. There is this obsession among schools to focus on their metrics and achievements… but they should be the very source of interrogation needed by society to purify itself from any kind of social stupidity.”

Without an objective, accurate approach to teaching martial law, Abellanosa continued, the same historical mistakes will be repeated. “Corruption is not new in the Philippines,” added Abellanosa. “But I think what we’re feeling right now is getting more intense. In this current political climate… I’m not even going to say I’m sad. I’m angry about the situation. It seems that we are a people na… murag natagak [as if we’ve fallen] sa mud, noh? And we don’t have the capacity to pull ourselves out from it.”