At 9 p.m. on March 14, salarymen and women all over the Philippines clocked out of work and tuned in to the initial appearance hearing of former president Rodrigo Duterte at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, Netherlands. There, he is detained, facing the Pre-Trial Chamber on charges of crimes against humanity — including murder, torture, and rape that took place under his administration between 2016 and 2019, and as early as 2011 when he was the mayor of Davao City.

According to ICC spokesperson Fadi el Abdallahthe, Duterte was authorized to join the hearing “at a distance,” or via video call, since “Mr. Duterte made a long journey.” But Salvador Medialdea, Duterte’s former executive secretary and sole legal counsel as of this time of writing, was present in the courtroom.

It was the perfect political drama for a Friday night, with a running time of approximately 30 minutes. The ICC website states there is a 30-minute delay on their stream. While commentators expected it to promptly start, as the Dutch do, at 9:30 p.m. Philippine time, Filipino viewers subconsciously anticipated some degree of lateness. Surely enough, as if by fate, the stream began at 10:05 p.m., carrying with it a familiar sense of delay all the way to The Hague.

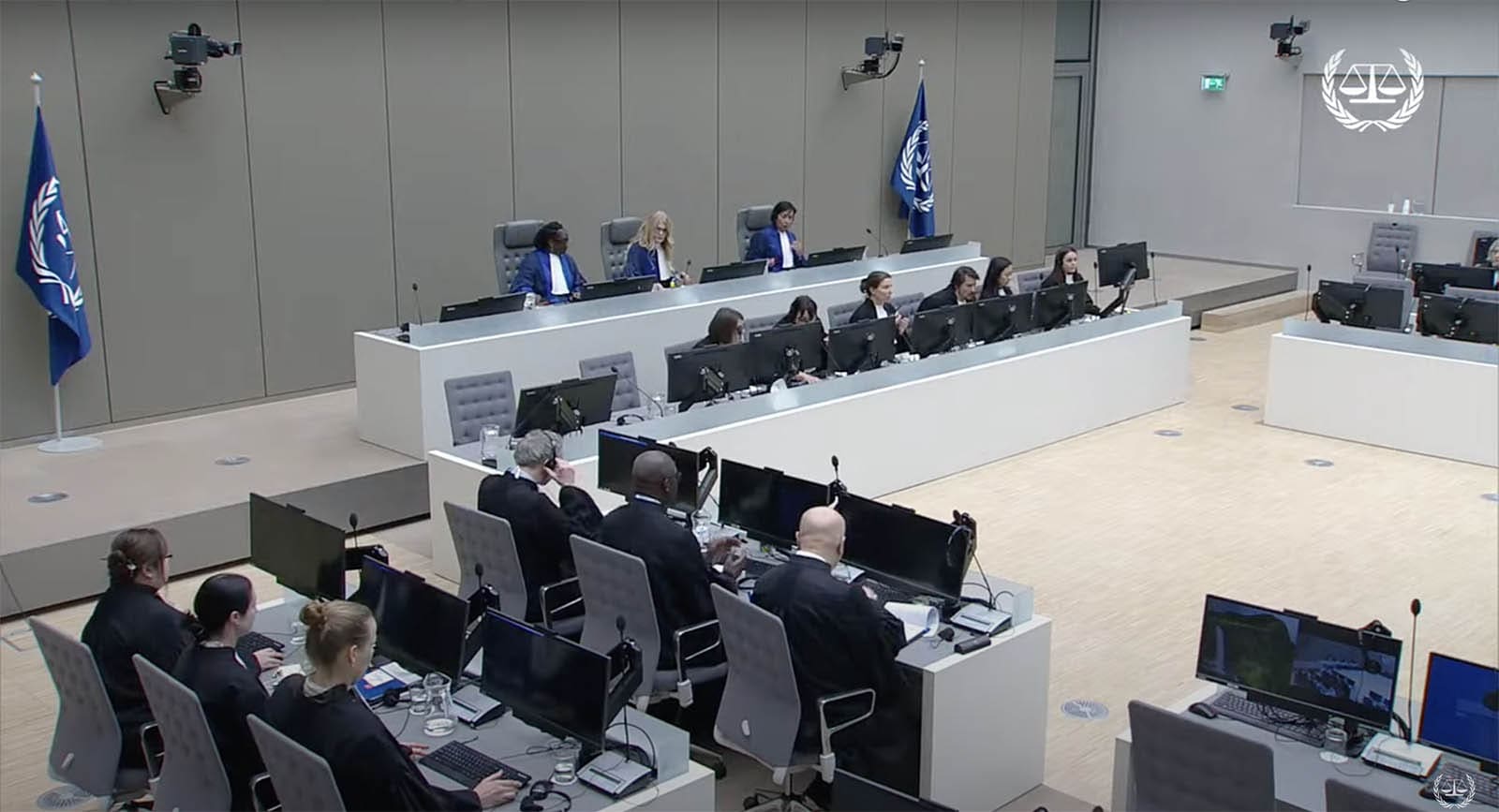

The standby screen transitioned to the clinical walls of the ICC courtroom; its accents of muted gray and soft, cool-toned blue forming a stark contrast to the warm, wooden fixtures of our Senate halls in Pasay City. After some preliminary questions where Duterte stated his name and date of birth, Iulia Motoc, one of three presiding judges who ordered his arrest, addressed Duterte in French with the utmost detachment. The purpose of the Pre-Trial Chamber, she said, is not to collect or present evidence, but to merely “answer three questions”: to ensure Duterte was aware of his accused crimes, to inform him of his rights as per the Rome Statute, the founding treaty of the ICC, and to set a date for the confirmation of charges hearing, which is September 23, 2025.

Political Theatre

Hearings in the Philippines are often tinged with hyperbole. For example, in September 2024, during the highly publicized Senate hearings on Philippine offshore gaming operators or POGOs, dismissed Bamban mayor Alice Guo denied to Senator Jinggoy Estrada of maintaining a romantic relationship with former Sual mayor Liseldo “Dong” Calugay, to which Estrada replied, “Artista ka, no? Mas magaling ka pa umarte saamin ni [Senator] Bong Revilla, ah!”

Meanwhile, the language in this European court is precise, technical, and dense. Motoc detailed word per word articles in the Rome Statute, as well as Duterte’s arrest warrant which accuses him of extrajudicially killing at least 19 alleged drug pushers through the Davao Death Squad, and at least 24 murders under the watchful eye of the Philippine law. (The ICC prosecutor’s office estimates as many as 30,000 drug war victims were under the hands of police or through vigilante killings.) Similarly, Motoc laid out Duterte’s entitlements, including his right to an interpreter, an attorney, and to remain silent.

Motoc’s tone was impersonal and devoid of emotion or force. While Medialdea’s retorts were similarly functional, he wielded a rhetoric that drew clear lines in the sand. Medialdea described the “political quar-settling” and “degrading fashion” in which Duterte “was bundled into a private aircraft and summarily transported to The Hague,” which, in legal terms, he called an “extrajudicial rendition.” “To the less legally inclined, it was pure and simple kidnapping,” he said.

Medialdea addressed the Chamber, stating how “two troubled entities” — the ICC and incumbent Philippine president, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. — “struck an unlikely alliance” in a “desperate” attempt “for a price cut,” seeking to “choke and neutralize” his client and his daughter, Vice President Sara Duterte. For an “elderly man” with “debilitating medical issues” to spend “more than five hours” on a layover in Dubai without legal counsel was, to Medialdea, “a gross abuse of process.”

It is, nevertheless, a process — one that 30,000 people were never due. Duterte’s private detention cell, housed in what once was a Nazi prison complex, is equipped with a library, computers, a kitchen, and medical staff, who, as per Motoc’s account, deemed Duterte “fully mentally aware and fit” to attend the hearing. Detainees also have a “daily program” that includes fresh air and recreational activities. Meanwhile, prisons in the Philippines are one of the most overcrowded in the world, many disguised as rehabs where “treatments” are designed to shame patients and invade their privacy — including random drug testing, facing a wall for 12 hours straight, or being withheld food for days on end. You’ll be damned if you progress there without being called a hopeless “adik” as if there’s no recourse for anyone suffering a debilitating disease like addiction.

The irony is not only the very humane treatment that Duterte receives as an alleged perpetrator of crimes against humanity — from an institution he once called “bullshit”; his legal team is prospected to include Harry Roque who, during his stint as Duterte’s presidential spokesperson, was complicit in state-sponsored brutality. Roque is also facing qualified human trafficking charges in relation to a POGO scam hub, and has gone AWOL since being cited in contempt and ordered into detention by Congress last September. The irony is in this bittersweet moment as Duterte gets his first taste of justice, one that many thought would never come or should never have happened at the cost of innocent lives. It is a new chapter for Filipinos who either enabled or endured his bloody campaign since his Davao City mayorship, which began in 1988 and saw the rise of death squad killings by the late 1990s.

Duterte is the first Asian former leader arrested on an ICC warrant. As other countries face their own mass atrocities, this initial hearing will mark the moment when the world first witnessed how international law exacts accountability at this scale. For Filipinos, it will test our ambivalence towards a legal system that, for generations, has felt like one big gaslight — even from the cold glow of our screens.

Sai Versailles is Digital Editor of Rolling Stone Philippines. She oversees the daily news report, in addition to covering music, politics, and counterculture.