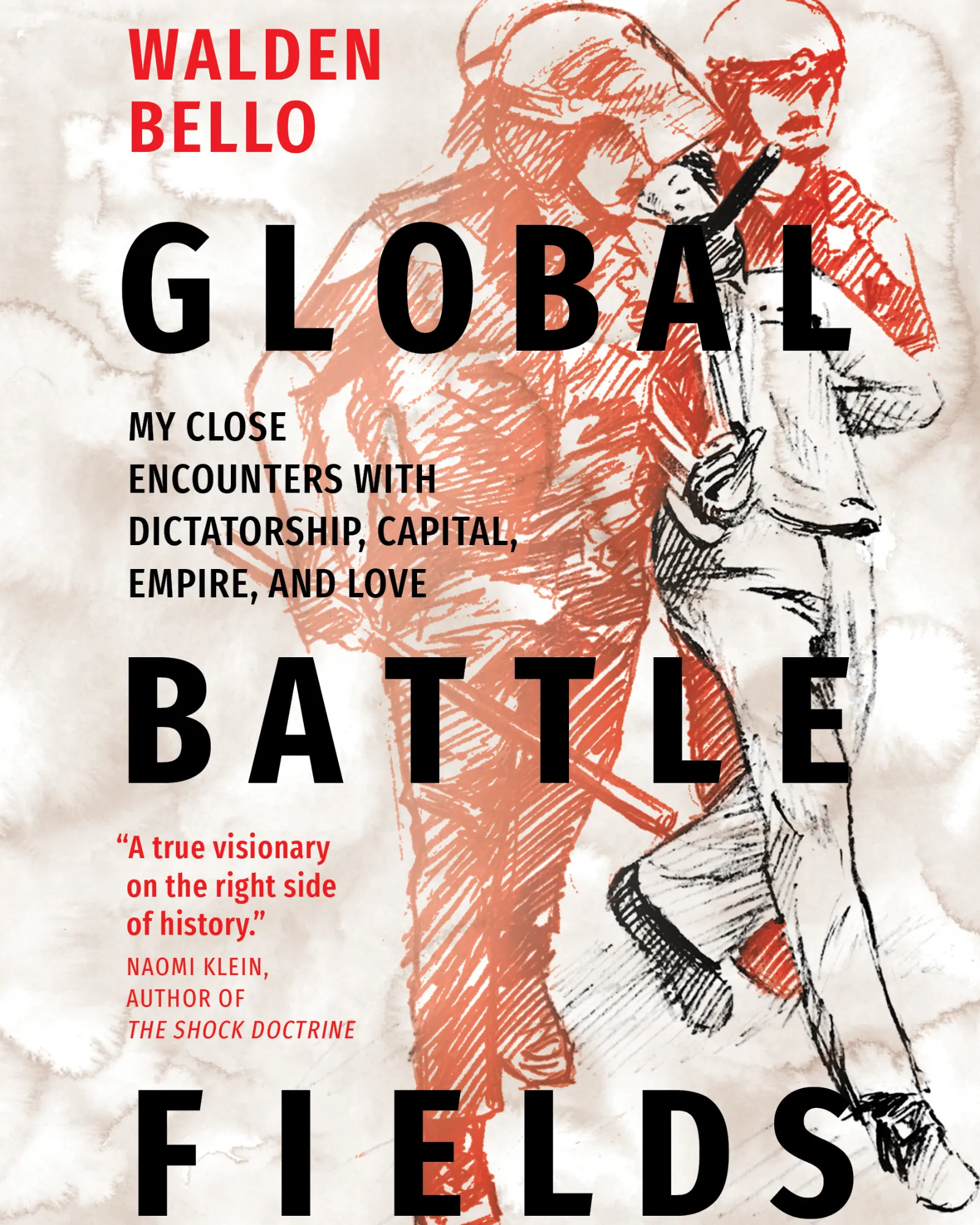

Before becoming the representative of the Akbayan party-list and serving as a congressman and vice presidential candidate in the 2022 elections, Walden Bello dedicated his life to a global quest for social justice. In the introduction to his latest book Global Battlefields, Bello details his evolution from student scholar to activist and, ultimately, his foray into Philippine politics.

Activism is the central thread that weaves his narrative together, tracing Bello’s journey from his childhood to studying in Ateneo de Manila University and Princeton, where he later transitioned from scholar to dedicated activist. Growing up in Manila, Bello recounts experiencing status dissonance, especially when his family moved to a middle-class neighborhood in Malate during the 1950s. There, he felt the gulf that separated him from his classmates who came from elite families. In the book’s introduction, he reveals that this is his first memoir, expressing his initial hesitation on whether his life story warranted such a narrative, as he believes that he failed significantly in the one area that mattered most to him: activism.

Thus, the global battlefields he recounts are diverse and many, with some ranging from documenting the counter-revolution in Chile leading up to the military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet in 1973, to his involvement in anti-globalization protests like the 1999 World Trade Organization demonstrations in Seattle, where he faced police brutality, or becoming involved in a daring heist in which he infiltrated the World Bank to steal over 6,000 confidential documents on its projects in the Philippines. This heist led to the publication of an underground book revealing the bank’s complicity in supporting former Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos, Sr. He even performed political comedy skits in Washington D.C., one in which he and his partner-in-crime dressed as Kermit the Frog and Miss Piggy in front of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) headquarters, claiming to be Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos seeking a loan for their regime.

In 1978, Bello and six fellow activists staged a bold occupation of the Philippine Consulate in San Francisco, blocking access to the entrance as police arrived to arrest them. In a show of solidarity, the group linked arms and sat on the floor of the consul general’s office, which led to a forty-five-day jail sentence after they refused to acknowledge the authority of the court. The group launched a hunger strike in protest and were eventually released two weeks later.

In our two-hour-long conversation, Bello recounted the same stories with the same laughter and mischievous glint in his eye. This is a man who has clearly lived many lives, while remaining wholly dedicated to fighting for the things he believes in.

While he is self-aware that he’s part of the “boomer generation,” he feels a more apt title would be the “revolutionary generation.” This conversation is a testament to the past and how, despite the failure of some global movements, there is victory in finding hope, in believing in a brighter future.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Can you talk about your childhood in Cardona, Rizal?

I was born [in Cardona], an island that my parents had purchased from an American back in the early 1940s. My parents and younger siblings lived there during the war. I was born right after the war and spent my first five years on that island. We were basically a middle-class family because my parents were in the entertainment business. They had been singers on the radio, and my dad was a businessman who promoted different kinds of films, especially from Hollywood. My mother was a poet and a writer, as well as a composer.

I grew up with a family that was artistically inclined. Although we had a middle-class upbringing, most of the people around Cardona, which is located in Laguna de Bay, were poor. In that community, a person’s status marker was not determined by land ownership but by the quality of their boat. I think this is typical of sea-going communities, that even if they are poor communities, they have greater freedom of action because they engage in economic activity.

So growing up, we really didn’t experience that kind of feudal relationships between landlords and tenants in other parts of the Philippines because this was a lake going community. And while we were regarded by the people as upper-class, my family had a very democratic relationship with the townspeople.

You mentioned in your memoir that you found being the child of artists to be challenging because they exist beyond the material world. Do you still view it this way, or do you now see it as a privilege that has inspired your journey as a writer?

Both. I think my parents received a very good colonial education, particularly in English, because they grew up in the 1920s and 1930s. They were both from the north, from Ilocos, so the two languages that were really spoken at home were Ilocano and English. Outside the house is where we spoke Tagalog. So, basically we grew up trilingually, but my mother really encouraged me in terms of writing. Both of them created opportunities for me, rather than forcing me into something. They loved the arts, they loved literature, and they encouraged us to read. I think artists march to a different drum than the rest of us. Unfortunately, we had relatives who sometimes stepped in, as my dad was forced into early retirement. So, they [my parents] were also living out their own adventure, a love story filled with ups and downs. I guess the point is that it was a privilege and it also came with a lot of struggles.

You studied in Ateneo where as a student you were well-aware of the class division between you and your classmates. While known for instilling values like compassion and empathy towards the poor, an Atenean education still lacks that solidity in advocating for social justice beyond peaceful means. Can you elaborate on this, and the status dissonance you experienced?

Yeah, I think that status dissonance was felt all throughout my college years. Of course, there were many of us in the same middle-class status, but most of the people that went to Ateneo came from the upper classes. My early rebellion had more to do in the realm of religion — basically I no longer, at some point, found religion and Catholicism relevant to my search for what was true. I did become an existentialist back when I was around second or third year in college.

So, my rebellion was initially anti-religious, existentialist, and individualist. In college during this time, you did not have the secular nationalist student movements that later became a very central part of the college scene beginning around the late ‘60s and ‘70s. Graduating back in the mid ‘60s, I really did not experience the student ferment that came with that period like the First Quarter Storm. The nationalism that was escalating in the University of the Philippines did not filter down Katipunan Road. So, that was my frame of mind when I graduated. I was in some sort of individual rebellion, but not as part of a collective secular movement. My rebellion was not political yet.

Your first act of activism happened while you were a PhD student at Princeton when you stumbled upon a protest in front of the Institute of Defense Analysis, where you joined a human chain of protesters. Did you ever envision yourself as an activist while you were in college, or did it happen instantaneously in that moment?

I came to the United States in 1969 to pursue graduate studies in sociology at Princeton University. When I first got into the United States, the war in Vietnam was raging. The kind of things we were reading in sociology were beginning to be progressive and Marxist-leaning sociological tracks. But I don’t think I was an activist. I was passing through that building, and I saw that there was a strike. The police came and started yanking people brutally, and before I knew it, I was among the people sitting in that human chain. I realized I had given up my sociological career because if you participated in any kind of political activity against the United States as a foreign student, at that point in time, you were automatically deported. But somehow I felt good because I had found myself.

I kept on waiting for the deportation order, but it never came. So my sociological career was saved, but I had become an activist in the process. Making that leap into that human chain was a very transformative kind of act that gave me a very strong sense that it is action that matters.

What I was trying to find was really the meaning of what we did, and that meaning was not just personal, but collective. My sense was that we may not have achieved the social transformation we wanted, but we made a difference.

I want to talk about the early ‘70s when you became an active participant in various organizations, including the Katipunan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino and the Anti-Martial Law Coalition. How was your experience within these groups?

I was in Chile for my doctoral dissertation when Marcos Sr. declared martial law in the Philippines. After that, I returned to Princeton to finish my dissertation. During that time, many individuals from the First Quarter Storm arrived in the U.S. and began forming activist groups in cities like New York, San Francisco, and Chicago. I joined and learned from them because, as far as I was concerned, I was a political neophyte in this movement, led by the Communist Party and the National Democratic Front, that was then spreading in the Philippines.

In organizing against Marcos within the Filipino community, our efforts were to get people in the U.S. Congress to cut aid to Marcos, while educating the broader U.S. public on what was happening in the Philippines. This required innovation, so we did things like protesting inside the Kennedy Center while Imelda Marcos was present and performing political comedy at the IMF headquarters.

But we had to find out what was happening with the World Bank, through which U.S. aid was being funded. So we eventually stole documents from the World Bank. This was necessary because we were in the United States, who were the main backers of Marcos, and we needed to expose the kind of relationship between their government and Marcos, who was receiving so much aid from them.

Initially, we formed a network of people within the bank that would smuggle documents out to us — people who supported our cause to bring down Marcos. But it was not enough. We needed to take more drastic action. Although it was very risky at this point, we impersonated World Bank people, pretending that we were coming from missions in Africa and Latin America.

Over the course of three years, we had about 6,000 pages of documents on all World Bank projects in the Philippines, which we eventually brought together into a book. That book was called Development Debacle, which was based purely on World Bank documents. No other country was able to be the subject of that because after we liberated all those documents and came out with the book, the security of the World Bank really tightened, and it became very difficult for anybody to come in and get confidential documents. So, ironically, it was the very success of our stealing documents that made it difficult to do a repeat of that with respect to another country.

What was going through your mind during those times?

I think we knew that if we were found out and arrested, we would definitely be charged with theft. But it was a risk that at that point in time, young as we were then, we were willing to take. If you’re young and you’re an activist, you’re willing to do anything. But we could not reveal how we obtained the documents until 1992, after the ten year statute of limitations on crimes committed, was reached.

Only then were we able to tell our story that we, in fact, robbed the bank. Was it my most memorable work? Probably. All I know is that at the time that I was writing it, I was writing it in an office near Dupont Circle in Washington D.C. where the traffic was just crazy. Every day when I crossed the streets in Dupont Circle, I prayed I would not be run over until I finished the book. That was the only time in my post-Christian life that I prayed because I just wanted to get this book out.

Are you still connected with the activists who were with you when you organized those demonstrations?

Yes, I went through several career transformations since then. I went back to the Philippines in the ‘90s to teach at the sociology department of the University of the Philippines Diliman, but I also founded an institute called Focus on the Global South in Bangkok. In many ways, I drifted away from the originally Philippine-centered movements, especially after the EDSA insurrection. But whenever I got a chance, I would try to hook back with old friends, and whenever we ran into one another, we would recount those days.

The reason for my writing was not only to find my personal meaning, but the meaning of my generation because my generation played a very key role in ending the Marcos dictatorship. At the same time, it also played a key role in the anti-globalization and anti-empire movements. So what I was trying to find was really the meaning of what we did, and that meaning was not just personal, but collective. My sense was that we may not have achieved the social transformation we wanted, but we made a difference. I just wanted to bring together in this memoir these experiences that I was part of, the experience of a whole generation, which is what I call the rebel or revolutionary generation.

I feel that writing this underlined both our victories and failures. It was only in the process of writing that I discovered, or was able to gain an insight into, the personal and collective meanings of what we did.

You were elected to the House of Representatives as the Akbayan party representative from 2009 to 2015. Could you share your experiences during this period?

While in Congress, I became one of the principal sponsors of the Reproductive Health Bill, as well as the Marcos Victims Compensation Act and the extension of the land reform law. Those are the three bills I was associated with. I also introduced the resolution to rename the South China Sea the West Philippine Sea; that resolution never got a vote in Congress because the [Benigno] Aquino administration, with whom I was allied at that time, told me I didn’t need to bring this to the plenary because they were going to change the name right now. So it became the West Philippine Sea.

I was also the head of the Congressional Committee on Overseas Workers Affairs (COWA), which required me to attend several meetings in the Middle East to investigate conditions there. It was a frustrating job because our people, especially domestic workers, were being exploited. We were trying to find protections for our Overseas Foreign Workers abroad, but it wasn’t there because the pressure to get out of the country was so great that people would do anything.

For instance, 90 percent of the OFWs in Syria during the Arab Spring in 2011 were undocumented, having entered through illegal means, and thus had no protections. Another thing I recount is our search for OFWs who might have fallen victim to the crossfire of the Syrian civil war. Unfortunately, that happened in so many cases. The problem for me was we could not simply apply Band-Aid solutions because the more fundamental problem was the neoliberal policies that crippled the economy and forced people out. That’s where we felt we had to really address the issue.

You resigned from Congress in 2015 due to conflicts with the former Aquino administration. What motivated you to remain a member of Akbayan after your resignation, despite the party leadership not backing your decision?

When I joined the liberal party coalition in 2010, we joined on the basis of as P-Noy put it, “Kung walang corrupt, walang mahirap.” That was the basis of the alliance. So, when [former] President Aquino began to exercise double standards and go after his enemies but protect his people, I argued [with him] about this, but he would not listen. At that point, I resigned because I could no longer support this administration. Since my party was still supporting him, I felt I had to resign as a representative in Congress of the party.

That was the only resignation of principle in the whole history of the Philippine Congress. But it had to be done, so we could tell people that there are serious people that take democracy and the anti-corruption campaign very seriously.

As for Akbayan, I respected my party but I gradually drifted away from it. I still see Akbayan as a major party for reform in the Philippines, although I’m no longer a formal member of it.

You also departed from the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) during the ‘90s. Could you talk about your decision of leaving?

I left the party after 15 years of being a cadre of the organization. There were two events that led [me] there. One was the decision to boycott the elections in 1986, which left the party looking on the sidelines as the insurrection or uprising against Marcos took place. I was part of that, I believed that the boycott decision was the right thing to do. But I also realized afterwards that I was part of a collective mistake.

The second thing that made me leave the party was a purge that took place. I investigated the Ahos campaign which resulted in the execution of several thousand party cadres, and I came out with a number of recommendations to the party — including the importance of people having individual rights, not just class rights. So this began a searching process on my part to come up with an alternative strategy whereby, as a left democratic party, we could become a major player in Philippine politics just like the CPP was in the ‘70s. But that was not something that was easily accepted as I was, at some point, branded as a counter-revolutionary.

That was an important break in my life. I think we still have major problems in the left, and what’s very much needed at this point is a unity of the different groups on the left that all splintered after the EDSA uprising. But we need to think out of the box, especially now where you have this big fight between two factions of the elite: the Dutertes and the Marcoses. So this is the time we need to really get our act together [and] influence the course of events again.

People said, ‘Yes, you’ve got a great program, but this is the wrong time.’ But when is the right time? When is the right time to bring an alternative, progressive program?

As somebody who’s lived through two Marcos administrations and played a pivotal role in diminishing the influence of Marcos Sr., do you believe that the experiences of those who came of age during the EDSA era significantly shaped their perspective on governance and reform?

Yes, I think there was a hope when EDSA happened and the Cory administration followed. There was an opening there for major reform legislation and minority rights, women’s rights. There was space to push perspectives and legislation that would bring our democracy away from just being dominated by elites, to becoming more rooted in the masses.

The 1987 Constitution has many good democratic aspects to it. But unfortunately, these laws were mutilated by the elites that used money in order to create, say, partylists that were really nothing else but channels for ambitious, elite politicians.

So a lot of the promises of the EDSA insurrection and the 1987 Constitution have not been fulfilled. It’s because of this frustration, of promises not being fulfilled, that many people have become jaded about reform politics and the EDSA legacy. Many of them have been taken up by a revision of history by the Marcoses, and populist appeals to eliminate crime and drugs by [Rodrigo] Duterte.

I think the inability of the forces that gained power from EDSA to deliver their promises created tremendous anxieties and resentments that were then channeled into the reelection and reconstruction of the Marcos myth. The promise of good governance, equality, an end to poverty, and real social democracy that many hoped for during the EDSA insurrection led to the disillusionment which contributed to the mystification of the Marcoses.

Considering everything you’ve said about the mystification of Marcos due to post-EDSA disillusionment, what was it like for you to run against [Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos, Jr.’s] party during the 2022 elections?

We knew that we were not going to win. I was running with Leody de Guzman. But we felt we had to run on a progressive program that’s probably the most elaborate democratic socialist program that has ever been elaborated. It touched on many concerns such as the raising of the minimum wage to contractualization, real land reform, LGBTQ+ rights, expansion of women’s rights, decriminalization of abortion, reintroduction of divorce. We felt that this was that time to push these issues into people’s consciousness.

It was important for us to promote this program, but at the same time we had no illusions we were going to win. But did we make a difference? I think so. It’s still a long haul, and part of it is progressives getting their act together and unifying to end this dynastic rule that has trapped the Philippines. Many people have supported the detention of Duterte in The Hague, but we should also realize that the Marcoses have become stronger as a result and that dynastic politics continues to reign in the Philippines. It’s a good outcome carried out by the wrong people.

Could you share your experience running for Vice President, given that it was your first time in that position? What were your most memorable campaign moments?

It was a campaign that brought us to the grassroots in Mindanao and Luzon. But I think people basically felt that they should vote for Leni [Robredo] because they felt that it was important to support them against the Duterte-Marcos faction.

I think people appreciated our [campaign], but nevertheless would not vote for us because of their worry that Marcos and Duterte would win. The votes for BBM and Sara were so high that they won by such a large margin over Leni that I felt those who believed they couldn’t support us should have done so — just to show that the democratic socialist program was worth supporting. People said, ‘Yes, you’ve got a great program, but this is the wrong time.’ But when is the right time? When is the right time to bring an alternative, progressive program? Because we might always be caught up in this situation of thinking that we must make sure to avoid the greater evil.

Another thing was I got a very good sense of how local elites are so powerful and ruined with impunity, especially against indigenous peoples. In fact, land grabbing was so rampant, because we went to areas where indigenous people asked us to go because they thought we could help [prevent] the juggernaut of land grabbing happening. My running mate, Leody de Guzman, accompanied the indigenous people, in the Manobos, in Quezon, Mindanao.

They were fired upon by the private security forces of the mayor of this area that also controlled the plantation there, which had deprived the Manobos of their land. We got a sense of how impunity rules within the local areas, and how local elites are very powerful.

Do you have any takeaways from that period that inspires you, even now in the current work that you do?

Yes, the connection with the people and their willingness to resist and fight in the face of tremendous coercive force. That’s sort of something that really has inspired me, that at some point, there needs to be a much more coordinated national effort by progressive forces to take up the causes of people. These are causes that the left in the ‘70s was able to bring together into a powerful force, and then lost it after the EDSA revolution. So, that’s really the challenge. Hopefully, people will abandon old ways of thinking and realize they have to get together to formulate a strategy to unite and to offer the people a vision that really inspires them. That’s the big challenge for the left.

In your memoir, you discussed the challenge of articulating your experiences to both older and younger generations, since the former grew up with a pro-American mindset while the latter lacks the context of your EDSA experiences. What advice do you have for the current generation, who may be unaware of these historical events but still want to make a difference?

The experience we had as a rebel in the revolutionary generation in the ‘70s and early ‘80s — that period of the progressive movement or the left was the driving force of change against the Marcos dictatorship. That was a movement that captured the imagination and the support of so many people in that generation.

On the one hand, the older generation of activists have, in fact, played their role. In many ways, it’s also time for them to open up the space for the younger generation to really take up the leadership. It’s important for both generations to engage in dialogue to make sure these experiences are communicated to the younger ones. So, we should try our best to communicate what it meant to be an activist during our period and present them with these experiences so they can critically reflect on it.

But again, what we really need at this point is action. I think inspiration is not enough and people who want to seriously change things must take the step of action. Whatever action that may take, whether it’s political action or determined engagement with people. Many others like me really dedicated their lives to what we felt was a quest for social justice. Things didn’t turn out exactly as we wanted, but nevertheless, I think that commitment of that generation was very central, and something that can be emulated by the younger generation.

Where do you see the future of Philippine activism?

I am quite hopeful that the younger generation will realize that things cannot go on as they’re going. We have an economy that’s devastated by elite control of land and neoliberalism, and we have dynastic politics that has become ever more brazen. I think that people will increasingly realize that they have to intervene, and that going out of the country is not the solution. In order for [the Philippines] to have a better future, you have to make a commitment to stay in the [country] and participate in the process of change. Youth has traditionally been rebellious [and] has been the ferment of change. So, my sense is that the Filipino youth will eventually come to the realization that they have to take it upon themselves to get the country out of its current rut.

Now, it won’t be an easy process. A lot of it will be trial and error, just like how it was for my generation. But nevertheless, we must not be afraid to make mistakes. The important thing is to learn not to make the same mistake twice. My generation’s challenge is to share our experiences — our failures and victories — so the younger generation can incorporate these lessons into their own journeys in order to chart out a path for the future.