In every State of the Nation Address (SONA) speech given by President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr., he has emphasized the importance of infrastructure through his “Build Better More” program, which covers projects in water resources, agriculture, health, energy, and physical connectivity. “Physical connectivity infrastructure—such as roads, bridges, seaports, airports, and mass transport—accounts for 83 percent of this program,” he said during his second SONA in 2023. “Our infrastructure spending will stay at 5 to 6 percent of our GDP.”

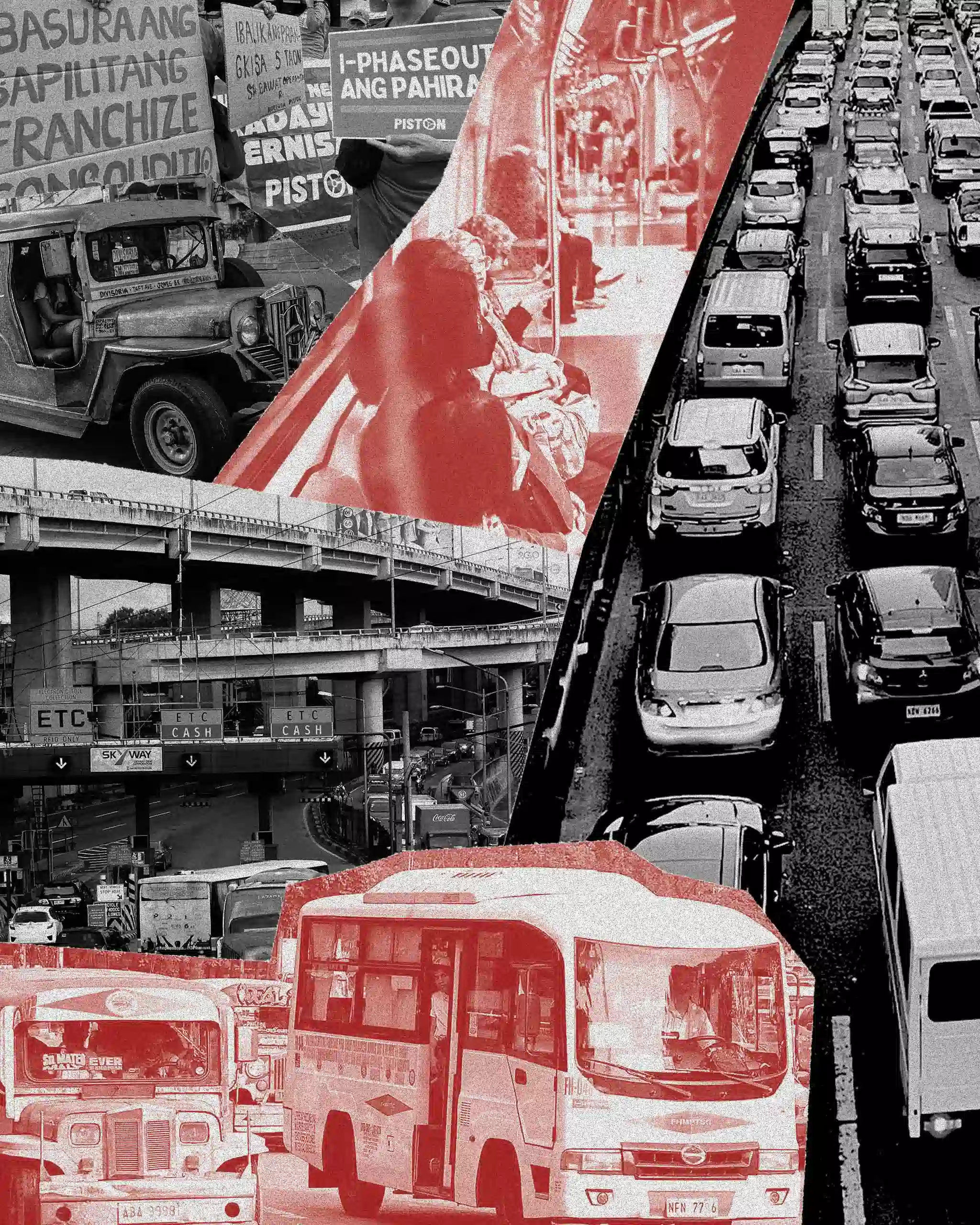

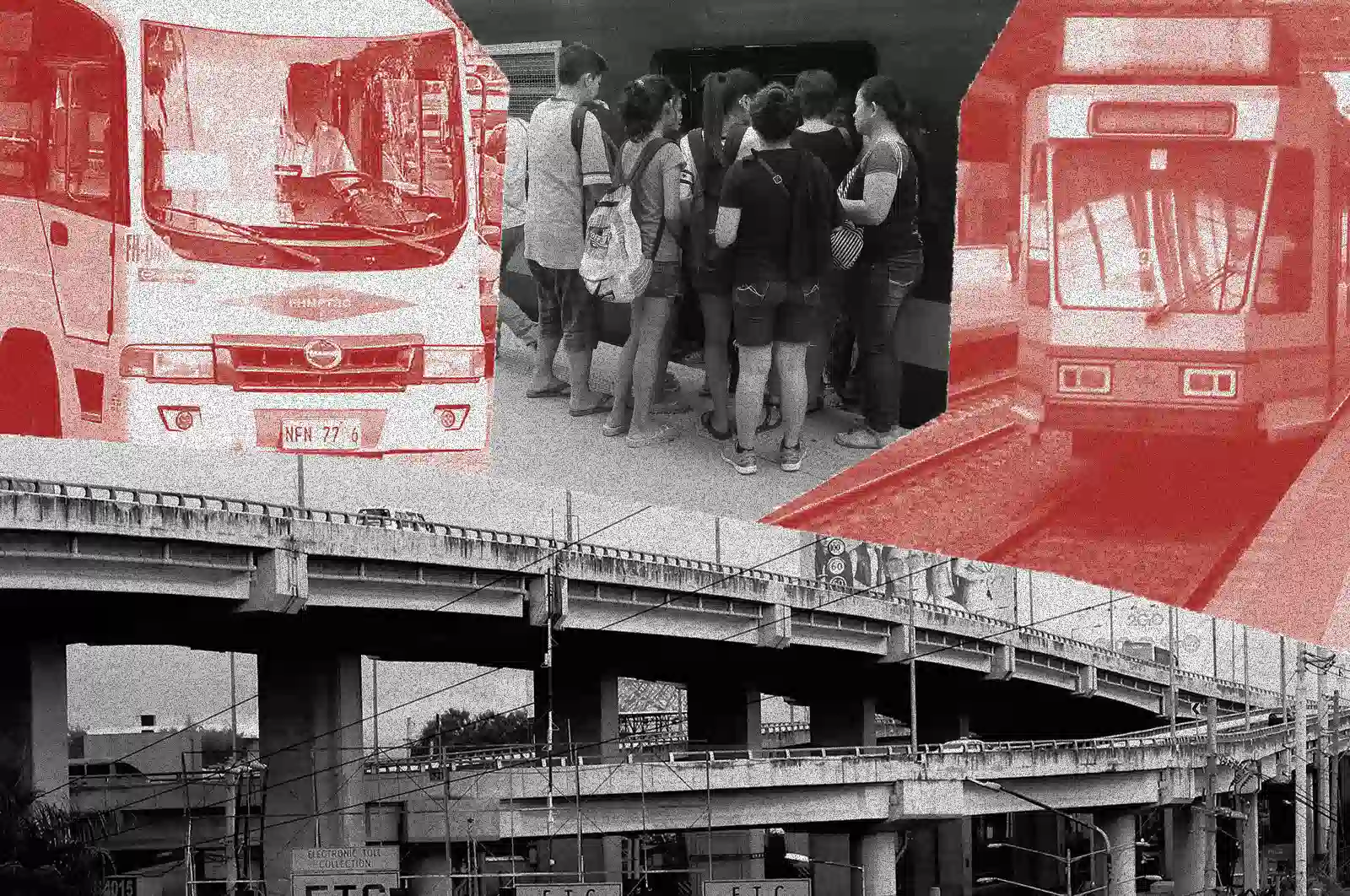

Across the Philippines, transport and mobility has become a daily calculation of time, money, and sheer endurance. In cities such as Bacolod, Cebu, and Metro Manila, commuters are adapting to systems that often feel stacked against them; transportation infrastructure lags behind urban growth, and the burden falls on those who can least afford it.

In Mindanao, the national government has yet to act on a major infrastructure project proposal, the Mindanao Railway. The proposed 10-phase project seeks to connect different parts of the island group, from Zamboanga del Sur in the west to Surigao del Norte in the east. With the project barely underway, heavy traffic remains a problem in Mindanao’s largest city, Davao City, which was ranked the third most congested in the world in 2024.

Meanwhile, in December 2024, Northern Mindanao was recognized as the top region in the country for its compliance with the Public Utility Vehicle Modernization Program, with its regional Land Transportation Office having processed 574,120 vehicle registrations, 265,973 license and permit issuances, and 29,989 traffic apprehensions, according to LTO-10 Director Nelson Manaloto.

Infrastructural Woes

In Bacolod City, 32-year-old artist Geli Arceño juggles multiple modes of transport just to get to work. She takes a Maxim motorcycle most days, but says the app isn’t intuitive for riders who need to indicate they’re taking it “angkas-style.” When she has more time, she opts for the jeepney or walks the 2.6 kilometers to her job at the Negros Museum. But the once-manageable traffic has worsened. “It takes me an hour to get home if I’m riding the jeep,” she says. “Sometimes you have to choose between spending your money or spending your time.”

For Arceño, the bigger issue is the dominance of private cars choking the city’s narrow streets. “Grabe na ang private cars sa Bacolod… It’s honestly what’s clogging the streets,” she says, adding that better public transport and flood mitigation should be priorities.

In Metro Manila, 22-year-old student AJ Raymundo takes a bit of everything: jeepneys, tricycles, UV Express vans, bikes, and increasingly, ride-hailing motorcycles. Since returning to Taguig City after graduation, his commute has become more unpredictable. “Now that I’m based in Taguig without train lines nearby… I’ve been using jeepneys a lot more,” he says. “Okay naman, convenient, kaso unpredictable lang.”

Raymundo describes public transport as a source of mental load, which is why, as he understands, some resort to using ride-hailing services. “The fate of our lives is so uncertain nowadays and the last thing you want to think of is how you’ll get to and from work.” He says he once dreamed of never needing to own a car, imagining a future where “the Philippines would have efficient public transportation.” Years later, that vision feels increasingly distant.

For working mom Corinna Pettyjohn, 43, cycling through Makati with her children has become the most practical solution. “It’s actually faster than either driving or taking public transportation,” she says, especially during school drop-off hours. But safety remains a key concern. “There aren’t a lot of protected bike lanes in the city,” she says. “Our cities are not ready for [kids] to bike to school.”

Inclusive Development

Beyond infrastructure, she also emphasizes the need for end-of-trip facilities. “We talk a lot about the bike lanes… but we tend to forget that parking, and even things like showers when you get to work, are just as important.”

In Cebu City, educator Riva Valles, 49, credits the Jeepney Route Code System for making commuting relatively easy to navigate. “This route code system also makes giving travel directions easier,” she says. But comfort and efficiency remain elusive. “Travel time is still longer as the roads are narrow and congested with the increasing number of private vehicles,” she notes.

Even the introduction of modern jeepneys hasn’t solved deeper structural problems. “They still load and unload passengers anywhere and tend to overload the vehicle,” Valles says. And without a train system in Cebu, mobility remains constrained by road traffic.

Across the archipelago, the stories differ in detail but echo the same structural problems: a public transit system that remains fragmented, reactive, and underfunded — and a mobility culture still centered around private vehicles. For now, commuters continue to adapt, but the calls for change are growing harder to ignore.