As we approach 2025, a year out of science fiction, it might do us well to find our bearings. I find literature to be, at its mildest, an entertaining distraction from everyday pain and boredom; and at its best, a necessity that nourishes the parts of us that make us human. The best books do both.

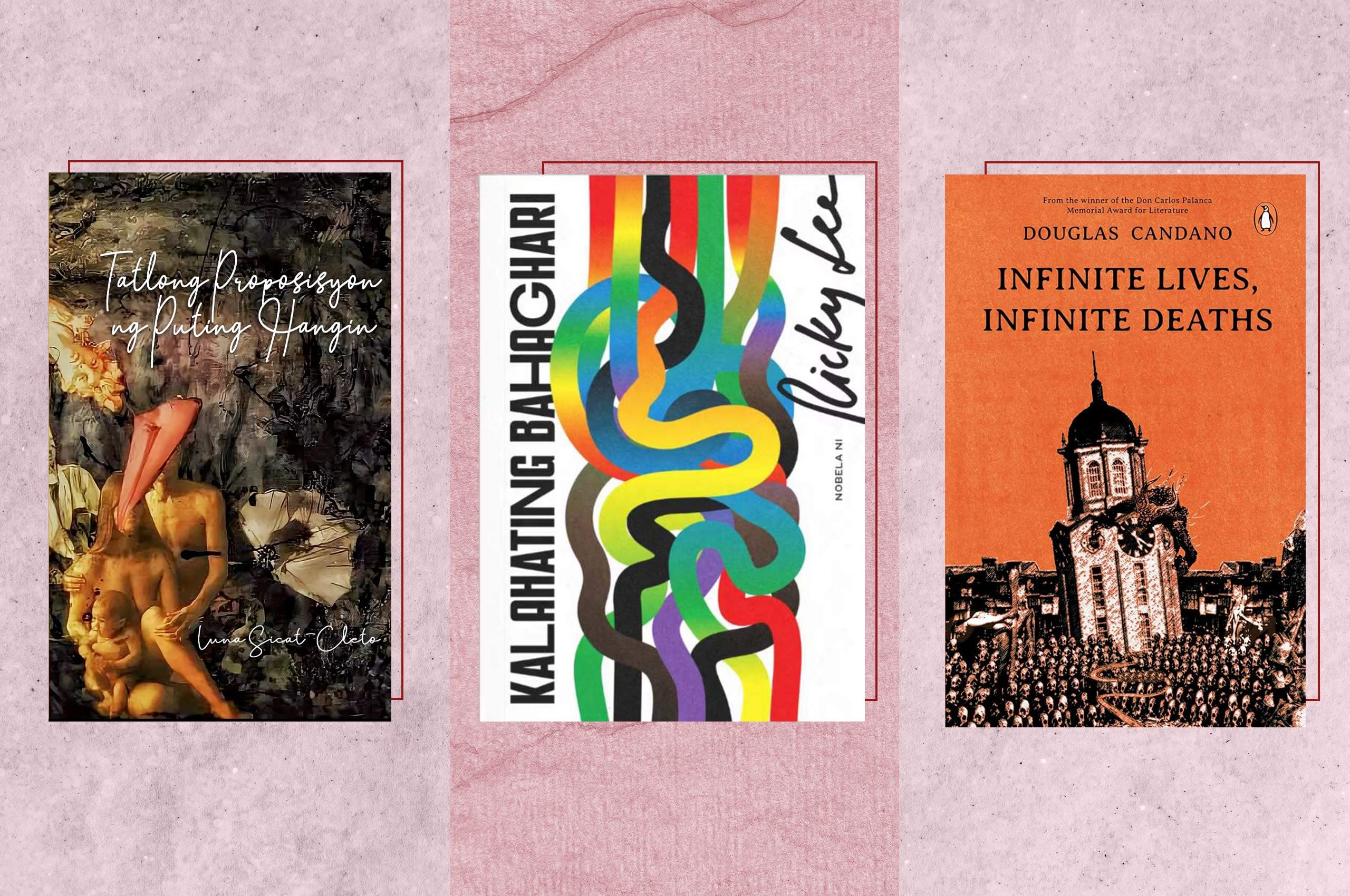

Here are my favorite books from Filipino authors in 2024, which scared, thrilled, and made me believe that better futures are merely slumbering in our collective literary and social consciousness.

‘Ang pinakaligtas na lugar sa buong mundo, ang mga bisig ng iyong minamahal’

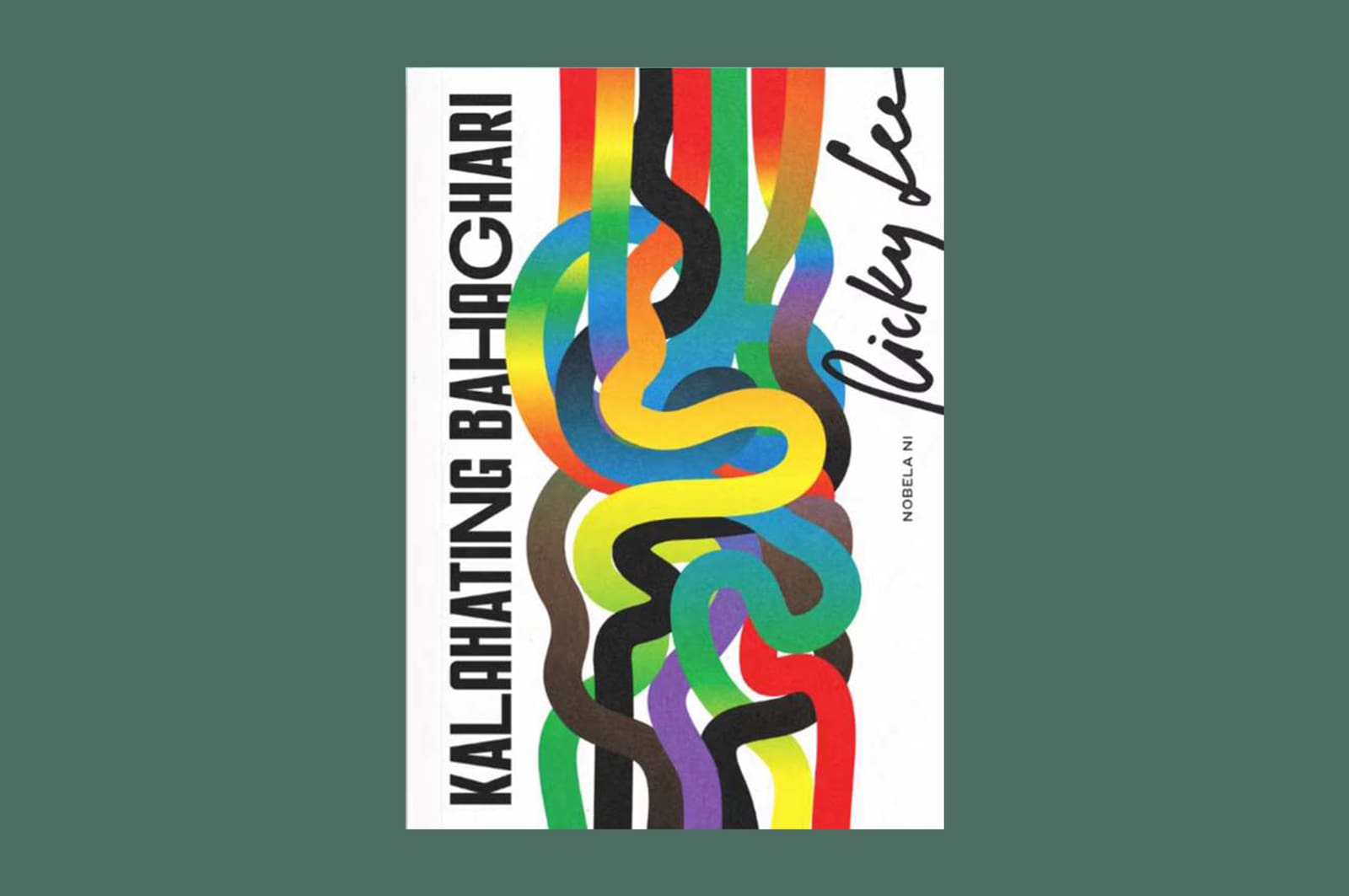

‘Kalahating Bahaghari,’ Ricky Lee

National Artist Ricky Lee gifted us this year with a barnstormer of a novel, Kalahating Bahaghari. The novel spans decades, chronicling the lives of a queer family. It opens in 1970 when Jim, a young gay man, comes out just before a devastating car crash. The accident claims his parents and his hearing, so Jim is left alone with his brother Luis, his bitter and homophobic sister-in-law Marina, and her brutal brother Oscar.

Marina enlists Oscar to “make Jim a man,” and Lee writes, with harrowing detail, the many indignities Jim is made to suffer through. Oscar mocks Jim at the slightest soft movement, narrates with fascistic glee the sexual abuse he inflicts upon captured activists, and almost makes him drink a glass of his piss before Luis finally grows a backbone and defends his brother. Lee renders clearly how the violence of martial law is the same kind of violence wreaked upon queer people: the disdain for anything loud or different, the insistence on a single, acceptable way of life, the violent molding of people’s minds and bodies to fit a narrow worldview.

Unlike other books, Kalahating Bahaghari allows its queer characters to revel in joy. Jim experiences two love affairs that are equally exuberant and heartbreaking. When his grand-nephew, Joshua, comes out to his mother, she humorously lists the several gay, trans, and queer people in his family. She also notes that it’s harder to accept him as a writer than as a gay man, considering the many toxic writers she’s met in her life.

In the latter half of the novel, set in the present day, Joshua deals with much more bearable struggles than the ones thrust upon his forebears. His barkada moans about their love lives at Pop Up in Katipunan. He navigates the complexities of dating apps and crushes on straight men. The violence that threatens queer people still looms over the characters, but the decades-long struggle of the queer movement has allowed Joshua and his friends more space to make mistakes and explore their desires. Lee’s deeply humanistic novel is required reading for everyone to help us embrace our own colorful humanity.

‘What is prophecy but the imagination changing reality?’

‘Ascension,’ Eliza Victoria

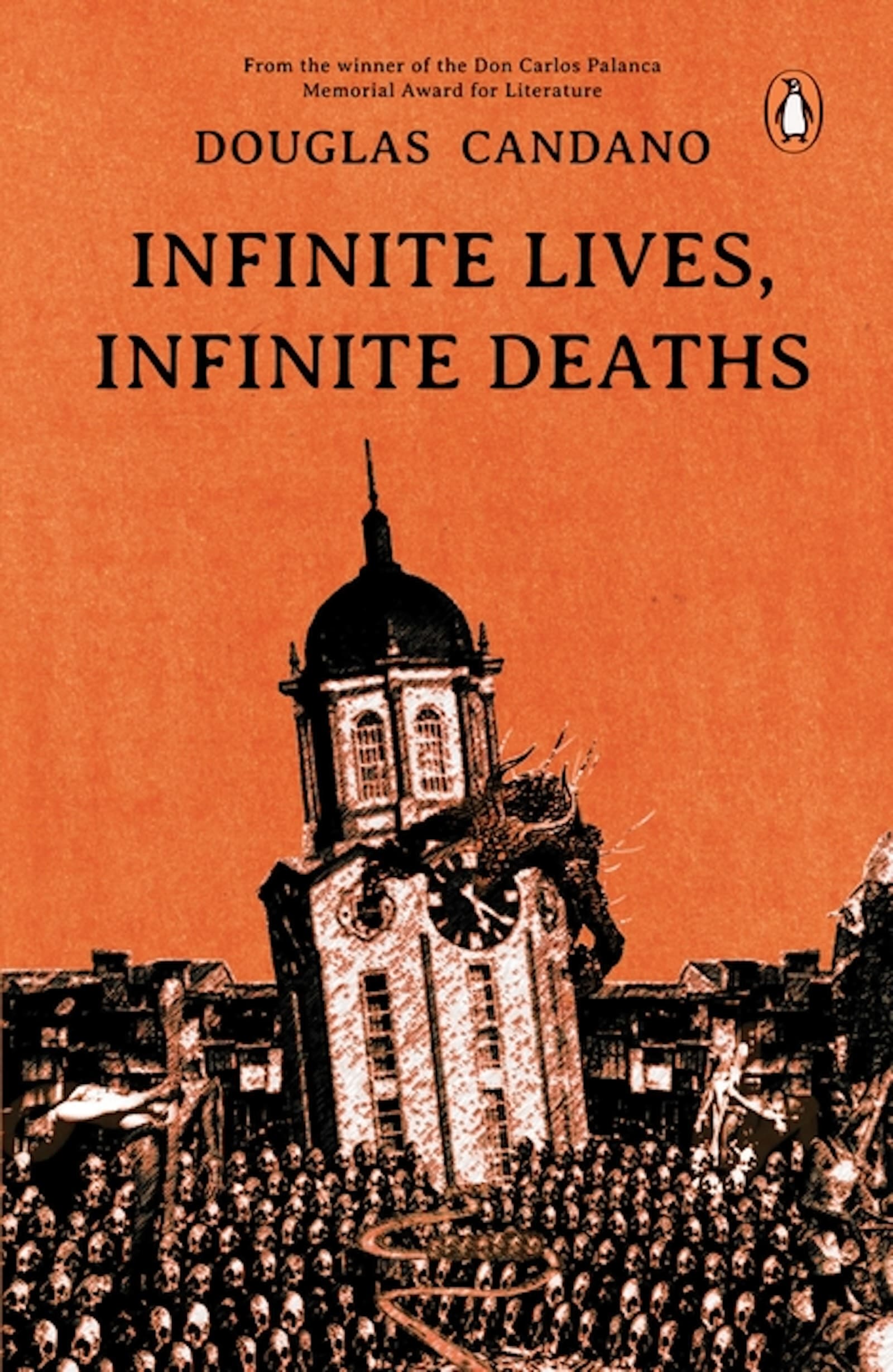

‘Infinite Lives, Infinite Deaths,’ Douglas Candano

Eliza Victoria’s Ascension and Douglas Candano’s Infinite Lives, Infinite Death are two remarkable works of imagination. Ascension brings to mind the Losers Club from Stephen King’s It: a group of friends in a small town come face-to-face with an unspeakable force that could bring them boundless wealth or a hell-on-earth.

A chance encounter with a childhood friend at a hospital reminds the protagonist, Emilia, of a promise she made in an old, decrepit house years before, and the ancient being that lived within it. When her friend collapses and dies in front of her, Emilia returns to her hometown and to the life and people she had left behind. Victoria evokes rotting houses, water-clogged corpses floating in rivers, sacred and profane time, and obscene rituals that bring the characters nearer and nearer to a great cosmic evil. Whereas the beings of Victoria’s previous novel Wounded Little Gods could be cruel, capricious, and benevolent, the god at the center of Ascension is a singular, malevolent entity that destroys the observer once she dares look at it, though Victoria’s breakneck prose compels you to read until the final, haunting image.

Meanwhile, Candano’s writing doesn’t signal anything awful until it’s too late. He adopts the language of an academic paper, grant proposal, or a report from a non-government organization to conjure a sense of comfort or familiarity before unleashing the most absurd grotesqueries. Lusty barmaids transmute into rotting corpses, a grand bazaar offers its customers glimpses into alien worlds, a girl is swept away by an otherworldly suitor and returns days later as an old crone. Of the many highlights of this collection, “The Way of Those Who Stayed Behind” best exemplifies Candano’s commendable talents. A Chinese-Filipino man comes home from Canada for his grandmother’s funeral. At her home, he finds a mysterious book about a menacing cult and realizes his own family’s involvement with its deranged prophet, and Candano times perfectly each bloody revelation to maximize the horror.

‘Gawin mo akong alagad ng iyong katahimikan’

‘This Is How To Mean No Harm,’ Martin Villanueva

‘Tatlong Proposisyon ng Puting Hangin,’ Luna Sicat-Cleto

Books from Luna Sicat-Cleto and Martin Villanueva push the boundaries of what genre and language are capable of.

In Villanueva’s collection, This Is How To Mean No Harm, the poet enthralls the reader with the kind of mordant, matter-of-fact humor that could only come from weathering the daily hardships of living in Metro Manila. A series of poems is entitled, “Because it’s year five of the shitshow and year two of the pandemic.” One of the poems launches a blistering tirade against former President Rodrigo Duterte and his war on drugs, while another lists the domestic and urban foibles that might lead one to contemplate suicide. Villanueva uses a cogent, conversational tone to make his personas confront the limits of their own mundanity and memory. He tells it as it is, eschewing banal observations and navel-gazing, and does not try to diminish or render simplistic everyday truths and failures. “The wee hours when I’m assured / of nothing else but wakefulness and a past,” he writes.

Finally, Sicat-Cleto’s Tatlong Proposisyon ng Puting Hangin veers into the bewildering and the weird. In her stories, a scorpion reaches enlightenment. A woman takes a temporal concept as a lover. The setting of “Ang Bayan ng Kosmopolit” resembles that of Samuel Delany’s mythical city Dhalgren. It would be inaccurate to call Kosmopolit a dystopia because Sicat-Cleto constructs a world even more alien than that: in Kosmopolit, caterpillar-shaped trains suck passengers into them, people take the Ultima Pill to better enjoy stimuli and stifle consciousness, and masks made out of “slow glass” function as the best disguises for Kosmopolit’s citizens.

The collection’s central stories all take place in a prestigious arts high school in the mountains of Los Baños and plumb the depths of hazing, elitism, loneliness, and the madness of the artistic process. Even in the more realist stories, the strangeness still glides beneath the surface. A kidney-shaped swimming pool’s surface reflects the school’s more pampered days of luxury. A mysterious woman makes the sign of the cross using her saliva on a girl who recently disappeared. Sicat-Cleto writes with a strength that would astound any reader.

Of course, anyone interested in reading more Philippine literature can sift through the rich catalogs of local publishers and university presses. But these five books are a good start for anyone looking for a good story, or a good time.