The Philippines has a toxic relationship with the Duterte dynasty. The drug war was popular — but also not quite, since most Filipinos disagree with the killings and feared for their lives. Support for former president Rodrigo Duterte’s case at the International Criminal Court has been growing, and almost half of Filipinos favored the impeachment of Vice President Sara Duterte earlier this year. After Duterte’s arrest in March, Pulse Asia found Sara Duterte’s trust rating rose to 61 percent. These fluctuations are a symptom of deep polarization and the complete opposite of “unity,” the only platform the Marcos-Duterte alliance promised when they were elected two years ago.

Between former president Rodrigo Duterte’s high-profile International Criminal Court arrest and the most recent Pulse Asia survey, the Duterte disinformation machine — a many-headed behemoth made of hyper-partisan influencers, anonymous trolls, and true believers — has cast the Dutertes as victims. Around 83 percent of online narratives were “deceptive” and “favorable” to Duterte, according to fact-checking initiative Tsek.ph. Philstar.com uncovered 200 accounts copy-pasting scripts that framed the arrest as a kidnapping. Online threat detection company Cyabara found a third of accounts on X discussing the arrest are fake. Rappler calculated that almost half of Facebook ads after the arrest supported Duterte — and Reuters points out most ads did not run with the required disclaimers for political advertising, a violation of Meta’s own policies.

It is reasonable to conclude, with Sara Duterte’s continued foothold, that these propaganda efforts are working. This exposes an inconvenient truth: Advocates of democracy and justice — and to an extent, the present Marcos administration — do not yet have a comfortable enough lead over the Dutertes.

Deeply Polarized

Pro-Duterte hardliners may be a minority, but their propaganda is designed to court a sizable fraction of undecided Filipinos with flexible opinions, swayable by emotion and first impressions on social media. Their narrative tactics include sowing doubt in extrajudicial killings and camouflaging as a solid majority through fake and manipulated photos. They also weaponize “false nostalgia,” as veteran journalist John Nery points out in an op-ed on Rappler.

Elections and public opinion are won on marginal differences. Behavioral scientist Sander Van Der Linden details in Foolproof: Why We Fall for Misinformation and How to Build Immunity that “not everyone needs to be fooled in order for misinformation to be highly influential and dangerous.” In Lie Machines, professor Philip Howard of the Oxford Internet Institute — the same group that discovered Duterte spent PhP 10 million on troll operations with up to 500 staff in 2016 — says the ideal result for such propagandists “is not a massive swing in the popular vote but small changes in sensitive neighborhoods, diminished trust in democracy and elections, voter suppression, and long-term political polarization.”

Depolarizing every small community — from church groups to schools — matters. But standing in the way are hyper-partisan influencers who shape online discourse and push otherwise soft supporters to the extreme. In today’s information pandemic, these characters are disinformation superspreaders. They muddy the waters with lies, vitriol, and the pseudo-intellectual mental gymnastics that comprise the “justification machine” where Duterte’s supporters source the rationale for their biases. Their talking points are amplified by foreign accounts and troll farms. Some of these personalities now face scrutiny at the House of Representatives, but most still retain their online platforms.

In a previous column for Rolling Stone Philippines, I argued that liberals and progressives must treat every day like a never-ending campaign. Now, I argue that they must take legal and technical action to “neutralize” black propagandists — not in the Dutertian sense of the word as killing, but rather to kill their reach. Serial disinformers may have a right to their (wrong) opinions, but they do not have a right to an audience.

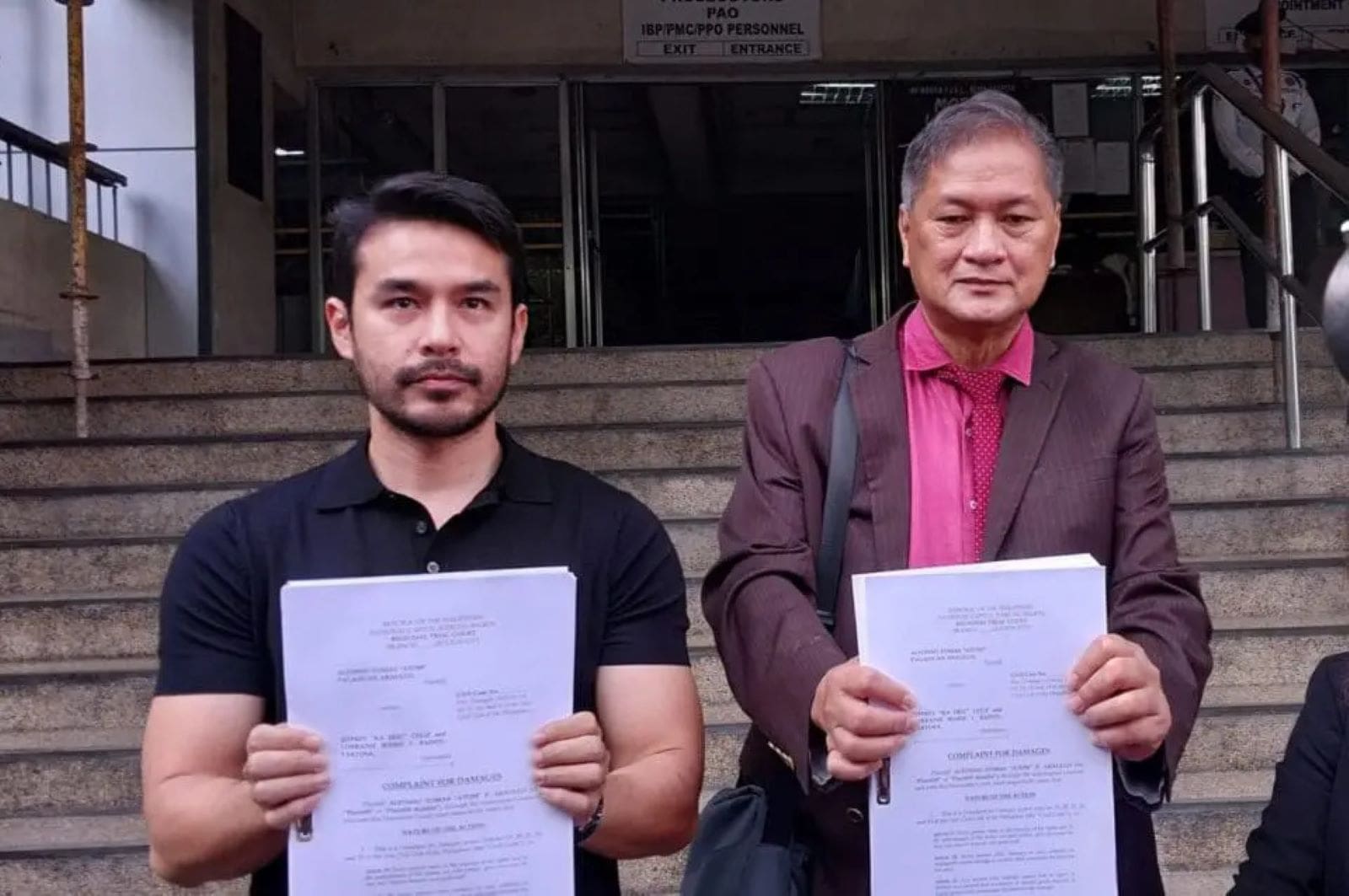

Some wins have been made in the last three years: Charges against Duterte critics Leila de Lima and Maria Ressa have been dropped, suggesting that at the least, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. will not intervene at the courts. Journalist Atom Araullo has won a landmark case for red-tagging, and hyper-partisan propaganda channel SMNI has been suspended from Facebook and YouTube. The Armed Forces of the Philippines, which once ran its own malign influence network under Duterte, has publicly committed to information integrity after being attacked by pro-Duterte trolls.

Democracy advocates should continue critically engaging Marcos in areas of potential alignments like big tech regulation, West Philippine Sea, foreign interference, and the drug war. But they should also take advantage of the current climate against Duterte, and shift from defense to offense. Opposition leaders and civil society should take disinformation superspreaders to two places: the court, and the Meta Oversight Board.

Legal Options

Freedom of speech does not mean freedom from accountability. The continued social media presence of disinformation superspreaders lets them go on empowering the worst of their supporters, all while reaping profit. Accountability-seeking should not be left to civilians alone. Prominent public figures should exhaust every possible legal means to disrobe these false prophets of their clout Former senators Sonny Trillanes and Kiko Pangilinan have filed such complaints, although these have not yet been enough to knock malicious operators off social media platforms for good.

In 2022, opposition leader Leni Robredo admitted that she regretted not acting early enough to dispel disinformation about her. In the same year, Darryl Yap, a director notorious for emotion-baiting incendiary content, ran a smear campaign featuring a puppet thinly veiled as Robredo, starring Imee Marcos to boot, which should have broken Commission and Election rules of conduct. The videos are still up online, both on Yap and Imee Marcos’ channels. As long as they stay there, they will continue to generate profit. Analytical tool Social Blade estimates Yap can earn anywhere between PhP 100,000 to PhP 1.7 million a year just from his YouTube account, where he has almost two million subscribers. Marcos, in the absence of any formal complaint for campaign violations at the Comelec, has aligned with the Dutertes and still vies for the coveted twelfth Senate seat this midterm.

Among opposition figures, Robredo — and possibly De Lima — have the most meat for winnable defamation cases. Evidence for black propaganda against Robredo is plenty: a rumored pregnancy and affairs, her likeness strapped to a bed and exorcised, and so on. At this point, a lawsuit is a social obligation — not only to her political allies, but all supporters of information integrity and good governance. While partisan influencers get away with the worst of their vitriol, they will continue to clutter the Internet, radicalize otherwise soft Duterte supporters, and train their target on others.

Civil Action

The second course of action is for civil society actors, possibly in league with opposition figures and families of extrajudicial killings victims, to test Meta moderation at the Oversight Board. The Board is an independent mechanism that calls the final shots on content moderation decisions.

Activists or coalitions like the Movement Against Disinformation can convene with disinformation researchers for a thorough accounting of failures in content moderation. Meta and other platforms have not only failed to curb the spread of harmful content, but — as pointed out in recent Rappler and Reuters investigations on pro-Duterte Facebook ads — they have been breaking their own rules, and turning a profit by doing so. Platforms’ shift toward community notes further complicates the fact-checking process.

Civil society should craft a strategic complaint to raise to Meta’s Oversight Board that could concretely result in the permanent ban of serial disinformers or certain content. Among the threads it could follow are the harassment of extrajudicial killings victims’ families and a rising conspiracy theory that the killings were a hoax.

However, the Board is not without flaws. Not all its decisions are binding, and their interventions can backfire. The case of Cambodia is informative: In 2023, the Oversight Board ordered the removal of a violent speech by its former prime minister Hun Sen, and he was recommended to be suspended from the platform (by that standard alone, many of Duterte’s own speeches could arguably be subject to removal). Preempting the ban, Hun Sen deactivated his page. Facebook complied with a takedown of the post, but not the page. Hun Sen has since returned to social media. As such, the strategic archiving of these pages — which can contain legal evidence — is necessary ahead of raising a complaint.

Nonetheless, an Oversight Board case can set a precedent internally within Meta’s own systems. If it fails, it still drives global public attention to the Philippine case. Data gathered and ensuing developments may even inform proceedings at the ICC, where witnesses have become targets of an intimidation campaign by the Duterte machinery.

With the Marcos and Duterte rift, there are windows of opportunity to secure precedent-setting, long-term wins that were not doable under Duterte. Of course, disinformation superspreaders retain their right to prove in court and tech platform mechanisms that their fallacies and cruelties are within the bounds of protected free speech. However, their online suspensions and bans after repeated community guideline violations and harmful content would free up poisoned algorithms. We owe our future selves the favor of carving out the breathing space for supporters of democracy to compete more fairly on propaganda-saturated platforms.

Regine Cabato was previously the Manila Reporter for The Washington Post, and a fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. She is pursuing a master’s degree in politics and international relations at SOAS University of London under a Chevening scholarship.