The Philippines — together with the rest of the world — has been fighting the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) for an excruciatingly long time. It has made significant progress, yet the public health emergency deepens.

Surge in HIV cases among youth first sounded the alarm. Then, shortly after, the United States paused its international funding, casting a shadow of uncertainty earlier this year. Coinciding with this is the show of power and influence of conservatives to hinder comprehensive sex education (CSE) in the country. These consecutive blows reveal one thing: the Philippines must confront these elephants in the room and take a decisive turn at this critical crossroads.

Anthony Louie David has been living with HIV for eleven years. His journey is a testament that HIV is no longer a death sentence and that individuals like him can lead full, ordinary lives. While his life is an inspiration to many, he knew very well how the global epidemic can be cruel. His familiarity with the effects of the virus stems from a deeply personal story after losing his beloved partner a decade ago to Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), the advanced stage of HIV.

“Mayroon po talagang progreso based on my experience, simula noong nagka-HIV ako. Mas napapalawak din ang tamang kaalaman. Pero nandiyan pa rin ‘yong takot,” David said in an interview with Rolling Stone Philippines. He even remembered a time before pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), a pill taken orally to prevent HIV sexual transmission, was made available in the country in 2017. “It’s just that habang tumatagal, mas dumadami at pabata nang pabata ang nagkakaroon ng HIV.”

In June, the Department of Health (DOH) released the first quarter data for the year 2025. By the health bureau’s estimate, at the end of 2025, there will be 252,800 people living with HIV (PLHIV) in the country.

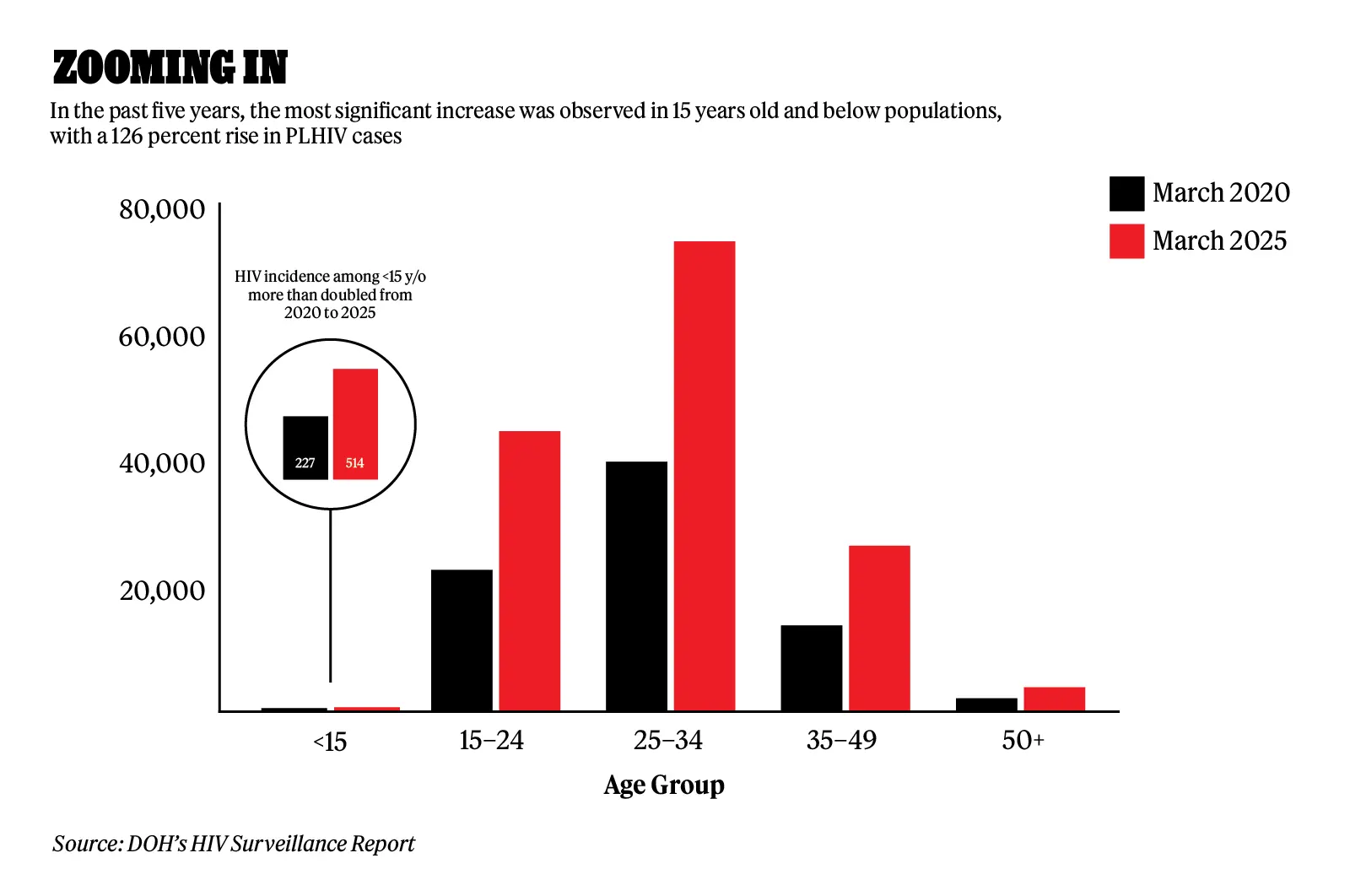

Of the 139,610 PLHIV, who have been diagnosed or laboratory-confirmed, and are currently living or not reported to have died, the highest proportion is among individuals aged 25 to 34 years old at 47 percent.

However, when compared to the data from the past five years, the most significant increase was observed in those below 15 years old, with a 126 percent rise, followed by the 15 to 24 age group, which saw a 98 percent increase.

“In 2013, we had at least an average of 13 cases per day… Nakita natin na sobrang dumadami ‘yong kaso at pabata nang pabata. It is really a public health concern that needs urgent intervention,” Joselito Feliciano, Executive Director of the Philippine National AIDS Council (PNAC), told Rolling Stone Philippines.

Pushed by the urgency of the situation, David has dedicated himself to HIV advocacy. Since 2014, he has maintained an undetectable viral load, meaning the virus is no longer transmissible. Despite this, he continues working in the frontline as a case manager at the San Juan Social Hygiene Clinic. After his working hours, he even volunteers at MyHubCares in Ortigas. Both facilities offer services for HIV treatment and care.

“Kaya pinapalawak namin as advocates ‘yong pagbibigay ng impormasyon sa community na nasasakupan kung saan kami nag-wo-work,” said David. “At the same time, talagang dinagdagan namin ‘yong pagbibigay ng testimonial para alam nilang mayroong PLHIV na nabubuhay sa mundo. Hindi kami parang sabi-sabi lang.” (According to DOH’s latest data, 66 percent of the diagnosed PLHIVs are currently on life-saving antiretroviral therapy (ART), a combination of drugs, or regimen that reduce the viral load to an undetectable level.)

Government and Civil Society Efforts

“Currently, we have a better and more harmonized response. We have a move in the PNAC to push for [a] whole of government approach. Ibig-sabihin, lahat-lahat tayo will have a role in the HIV response, especially in intensifying knowledge about basic HIV, prevention, and access,” said Feliciano.

The increasing cases of PLHIV among the youth are attributed not only to risky sexual behaviors but also to the recent changes brought by the Philippine HIV and AIDS Policy Act of 2019. This law allows minors aged 15 to 17 years old to be tested for HIV even without parental or guardian consent, repealing the Philippine AIDS Prevention and Control Act of 1998, which previously mandated parental or guardian consent as a requirement for individuals aged 18 and below. Minors have always been affected by the virus, but they have only recently gained easier access to screening, previously constrained by the need for guardians’ consent. Hence, the new law becomes an enabling environment for these minors to finally know their status more openly.

PNAC comprises 14 national government agencies and eight civil society organizations as members of its council, with the DOH at the helm. Feliciano noted that the ongoing fight against HIV has engaged more government agencies. Given the alarming rise in cases among the youth, PNAC has been coordinating with the Sangguniang Kabataan to intensify information dissemination in the youth sector at the barangay level, with the support of their member-agency Department of Interior and Local Government.

“Ang HIV po is not just a problem of the health sector,” Feliciano added. “Problema ito ng buong bayan. Lahat po tayo, we have to give our contribution to the HIV and AIDS response.”

Many of the Philippines’ leading civil society organizations receive support from the Global Fund, an international financing organization that mobilizes and invests resources to fight HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. Its principal recipient for the grant cycle 2024–2026 is the Pilipinas Shell Foundation, Inc. The grant is distributed among three key sub-recipients, each focusing on a critical aspect: LoveYourself for key populations, IDEALS for human rights, and Sustainable Health Initiatives of the Philippines (SHIP) for field operations and service delivery.

Mark Angelo de Castro, SHIP’s strategy manager, explained that their primary role is to collaborate with local government units to strengthen their social hygiene clinics, dedicated healthcare facilities that primarily focus on preventing and treating sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In addition, they conduct community outreach programs in partnership with local leaders, school administrators, workplaces, malls, and even events such as festivals and pageants.

“We call it providing ‘differentiated care’ to our clients. Back in the day, ‘yong mga naunang program ay limited ‘yong types of services being offered. Right now, our field staff and units go out to the community to look for their needs and challenges. It is tailor-fit sa kanila. We design activities relevant to their interest, while also looking at what is mandated by our job description,” said de Castro.

“Ang HIV po is not just a problem of the health sector. Problema ito ng buong bayan. Lahat po tayo, we have to give our contribution to the HIV and AIDS response.”

There are more than 70 hospitals and medical centers that provide outpatient and inpatient HIV treatment care, and 47 primary HIV care facilities nationwide. The list from LoveYourself provides both the government and civil society with facilities.

The harmonization between government and civil society is essential. Feliciano emphasized that the national government cannot operate in isolation, as civil society brings both expertise and deep community engagement. However, despite their collaboration, a significant challenge looms over both sectors: the reliance on international development funding, and the pressing need to achieve self-sufficiency.

Building Self-sufficiency Amid Consecutive Blows

The U.S. government under President Donald Trump has dealt successive blows to the global fight against HIV. Just this May, the administration moved to terminate $258 million in funding for HIV vaccine research. It also withdrew financial support for the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), which accounted for 40 percent of the program’s total revenue.

The blows started at the onset of this year when Trump issued an executive order on January 20, halting the distribution of funds for foreign development assistance programs. This directive affects initiatives such as the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), a $7.5 billion program managed by the State Department.

More than 20 million PLHIV around the world are directly receiving support from PEPFAR and will be affected by Trump’s decision. However, the US Secretary of State approved an “emergency humanitarian waiver” allowing continuous access to HIV treatment funded by the U.S. across 55 countries worldwide. However, the waiver has not been fully implemented in most countries. The PEPFAR funding freeze extended beyond 30 days, with no significant announcement from the Trump administration on whether the funding will resume or not.

DOH reassured the Filipino public that health services would remain unaffected despite reports of a temporary suspension from the U.S. Similarly, LoveYourself initially assured the public that essential services — including testing, treatment, PrEP, and self-testing kits — would remain available and fully operational for free.

However, this issue is just the tip of the iceberg. Even before the U.S. freeze order came into play, discussions between the government and the development sector had long been underway. Moreover, while a waiver has been issued, the U.S. withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO) — another Trump move — could further threaten funding for HIV programs.

“Ito ‘yong pinag-uusapan dati pa: ‘yong transition plan. Dapat malinaw sa atin ‘yong mga pangangailangan natin, magkano at saan natin kukunin ‘yong mga kapalit. Ginagawan natin ng paraan how can we sustain the human resource and initiatives of our HIV and AIDS response,” said Feliciano.

UNAIDS Philippines pushes the Philippine government to step in to shoulder the funding for HIV mitigation efforts. Its country director, Louie Ocampo, said that DOH developed an HIV co-financing plan for 2024 to 2026 with a required budget of P45.6 billion for health-related plans. However, UNAIDS identified a funding gap of P22.4 billion. Their agency also has to suspend six ongoing projects with the government and other partners due to Trump’s executive order, as the scope of the waiver only includes HIV treatment programs, which are classified as “life-saving humanitarian assistance programs.” The suspended projects of UNAIDS aim to craft a national strategic plan and other initiatives on HIV.

Global Fund has allocated $25 million for the HIV program of the Philippines for 2023 to 2025. In the first year, $11 million was disbursed, while $7 million was utilized in 2024. The remaining $7 million is to be used for the current year.

The 7th AIDS Medium Term Plan, the main blueprint of the Philippine government to fight HIV, states that 94 percent of the HIV financing is expected to come from domestic sources and only a mere six percent from external sources. However, based on their assessment, a 60 percent funding gap remains at the national level.

“We do not talk about sex in our homes and schools. It is a taboo topic. Ang laking issue ng comprehensive sexual education. If you cannot talk about sex, how can you talk about HIV? That is why it is a big number. We do not arm the Filipino people with the knowledge, we do not give the people the opportunity to protect themselves.”

While the consecutive Trump moves did not affect the Global Fund and other external funding, it puts HIV frontliners like David in a constant state of fear and dilemma. “Hindi namin alam kung hanggang kailan kami… Pakiramdam namin at risk kami. May worry kung ma-re-renew ba kami.”

De Castro said that the Philippines is not yet ready in the event that the majority of the external funding is revoked. He added that it could paralyze the operations of some organizations funded by international development partners. “In our case alone, we have four facilities located in Calamba, Cavite, Makati, and Caloocan that are operational through the funding of the U.S.”

The push to be self-sufficient in the fight against HIV is possible if it becomes a priority for the public, Feliciano said. Most of these foreign aids were initially granted on the condition that they would only act as transitional assistance to support beneficiaries on their way to self-sufficiency. Feliciano cited as an example the introduction of ART, which the 2018 law specifically sought to provide. “Before, this was being donated by the development funders, Global Fund, but ngayon, tayo na. It is the Philippine government that buys and distributes these free antiretrovirals. Ganoon ‘yong mga plano na mayroon tayo.”

PNAC has a budget of P50 million for 2025, according to the General Appropriations Act (GAA). It is six million higher than the 2024 budget, but P2 million short of the proposed budget of the Department of Budget Management.

“[Building self-sufficiency] is not a matter of whether we can do it or not. We have no other choice,” Deano Reyes, a sexual health and HIV primary care doctor, told Rolling Stone Philippines. “We have to reallocate funds to the HIV program. We have to be more proactive in HIV prevention rather than reactive.”

Barriers and Contradictions

Aside from the institutional challenges from the service providers, Reyes said that the major barrier in the collective approach to HIV is the sex-averse and conservative culture in the country. This notion is also indicated in the medium-term plan, citing cultural and religious taboos as the first historical, cultural, and institutional barrier in the country’s HIV and AIDS response.

“We do not talk about sex in our homes and schools. It is a taboo topic. Ang laking issue ng comprehensive sexual education. If you cannot talk about sex, how can you talk about HIV? That is why it is a big number,” said Reyes. “We do not arm the Filipino people with the knowledge, we do not give the people the opportunity to protect themselves.”

He emphasized that while the government is doing a good job in making sure that services are accessible through the facilities and treatment packages, there still needs to be stronger intervention, political will, and implementation of sex education.

“It starts in education. It is teaching kids that HIV is only a disease, some people get it, at hindi siya dapat pandirian. There are people who are just sick. Unfortunately, hindi ganito ang sitwasyon. The stigma pervades,” Deano added.

“It starts in education. It is teaching kids that HIV is only a disease, some people get it, at hindi siya dapat pandirian. There are people who are just sick. Unfortunately, hindi ganito ang sitwasyon. The stigma pervades.”

Sex education has been the center of the ire of conservative and religious groups recently, as it is a component of the proposed Anti-Teenage Pregnancy Bill. Conservative groups under Project Dalisay, an initiative by the National Coalition for the Family and Constitution, expressed their concerns over “international guidelines” and what they believed to be teaching of “early masturbation.”

This backslash caused senators to withdraw their support for the bill. In response, Senate Deputy Minority Leader Risa Hontiveros, the principal author of the bill, filed a substitute bill to remove the provision stating “guided by international standards.” Sex education will also be limited to children aged 10 years old and above in the updated bill.

“Ang totoong pangbubudol ay ‘yong ginawa ng mga nag-fake news laban sa bill… nagkalat ng disinformation at nanakot sa ating sambayanan sa pamamagitan ng kanilang social media operations,” said Hontiveros in a press conference last January.

Hontiveros argued that the Supreme Court already ruled in favor of the constitutionality of CSE under the Reproductive Parenthood and Reproductive Health Law. Since 2018, DepEd has also been offering CSE through the schools of their jurisdiction. The CSE in the proposed bill seeks to extend the coverage to out-of-school youth, parents, and teachers.

HIV, AIDS, and other sexually-transmitted infections (STIs) are among the key topics included in the CSE, together with human sexuality, informed consent, effective contraceptive use, sexual abuse and exploitation, gender equality and equity, and gender-based violence, among others.

“Sexual education is not a live demo of sex. What sexual education is about is consent, knowing your body changes, feelings, and teaching them how to properly process these things and respond in a healthy way,” said Reyes. “You would be surprised by how many professionals I get in my clinic — lawyers, engineers, politicians, and fellow doctors — who do not have any idea about HIV, or STIs.”

The Philippines faces both internal and external challenges in its HIV response, from funding constraints to cultural resistance. The community stakeholders and frontliners, both as subject matter experts, have also enumerated problems in manpower, access to services for people in geographically isolated and disadvantaged areas, and the prioritization of local governments, among others. But in the end, they emphasize the need for a multi-sectoral approach, stronger political commitment, and public awareness to address this public health crisis effectively.