Cinemalaya was founded in 2004 through the efforts of the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP), the Film Development Council of the Philippines (FDCP), the University of the Philippines Film Institute (UPFI), and the Philippine Multi-Media Systems Inc., chaired by business tycoon Antonio “Tonyboy” Cojuangco, who served as the festival’s principal benefactor.

On the one hand, Cinemalaya chiefly intended to be a space for the discovery and development of “cinematic works of Filipino independent filmmakers that boldly articulate and freely interpret the Filipino experience with fresh insight and artistic integrity.” On the other hand, it served as a content-feeder for Cojuangco’s Dream Satellite TV, which ceased operations in 2017. It’s a conflict of interest that Cinemalaya would inevitably have to contend with, a stubborn asterisk that could jeopardize its notion of “free cinema,” hence the festival’s name.

Cinemalaya’s primary draw is that its process leans on raw scripts and concepts instead of finished films, a template later adopted by Cinema One Originals and the FDCP. It starts with an open call for submissions; then a selection of 25 semi-finalists for its New Breed section, featuring young and debuting directors, and 10 semi-finalists for its Directors’ Showcase section, featuring established filmmakers; followed by an incubation program and a selection of 10 finalists and five finalists for New Breed and Directors’ Showcase, respectively. (The bifurcation of the feature-length categories began in 2010, only for the festival to scrap it and revert to the regular Main Competition program in 2016, with its competitive short counterpart still intact.) The year- long process will then proceed to casting auditions, workshops, monitored production and post- production work, leading to the festival run and awarding of prizes.

The digital film competition and festival saw its first iteration in July 2005, with nine full-length entries and six shorts screening for five days in four CCP venues, competing for the Balanghai Award. It was rounded out by its Film Congress, a series of panel discussions steered by film scholar Nicanor Tiongson.

Cinemalaya has broadened its horizon since. The festival now runs for 10 days. Its programming, at least since 2007, expanded to over 100 films screened per edition, including in-competition full features and shorts, exhibition titles, retrospectives, and premieres, alongside film forums, talkbacks, and book launches. In 2024, the festival exhibited a total of 200 titles. Its initial half-a-million-peso seed grant to selected full-length entries also improved to P1 million per title in recent years, peaking in 2023, where each film received P2 million. Similarly, Cinemalaya’s spectatorship grew, from a modest 8,440 total audience count in 2005 to over 100,000 in 2014, per CCP’s data. By indie metrics, it is already a huge leap.

In a span of two decades, Cinemalaya has indeed shaped and, to some extent, sharpened the trajectory of independent moviemaking, of Philippine cinema that, from time to time, is believed to be near its terminus. Keen to its purpose, it has ushered in “a new breed of Filipino filmmakers” — the likes of Adolfo Alix Jr., Sigrid Andrea Bernardo, Jade Castro, Arden Rod Condez, Sheron Dayoc, Pepe Diokno, Zig Dulay, Hannah Espia, Teng Mangansakan, Chris Martinez, Anna Isabel Matutina, Pam Miras, Thop Nazareno, Mikhail Red, Auraeus Solito (now Kanakan-Balintagos), Jerrold Tarog, Dan Villegas, and Alvin Yapan — whose visions, like many great pictures of the past, gesture toward the development of what Lino Brocka has termed “The Great Filipino Audience.” Their ideas run the gamut, from granular to gargantuan: romance, religion, poverty, crime, labor and displacement, gender, homoeroticism, healthcare, politics, human rights, state violence, environmental plunder, war, film culture, and new media, and all their knotty intersections.

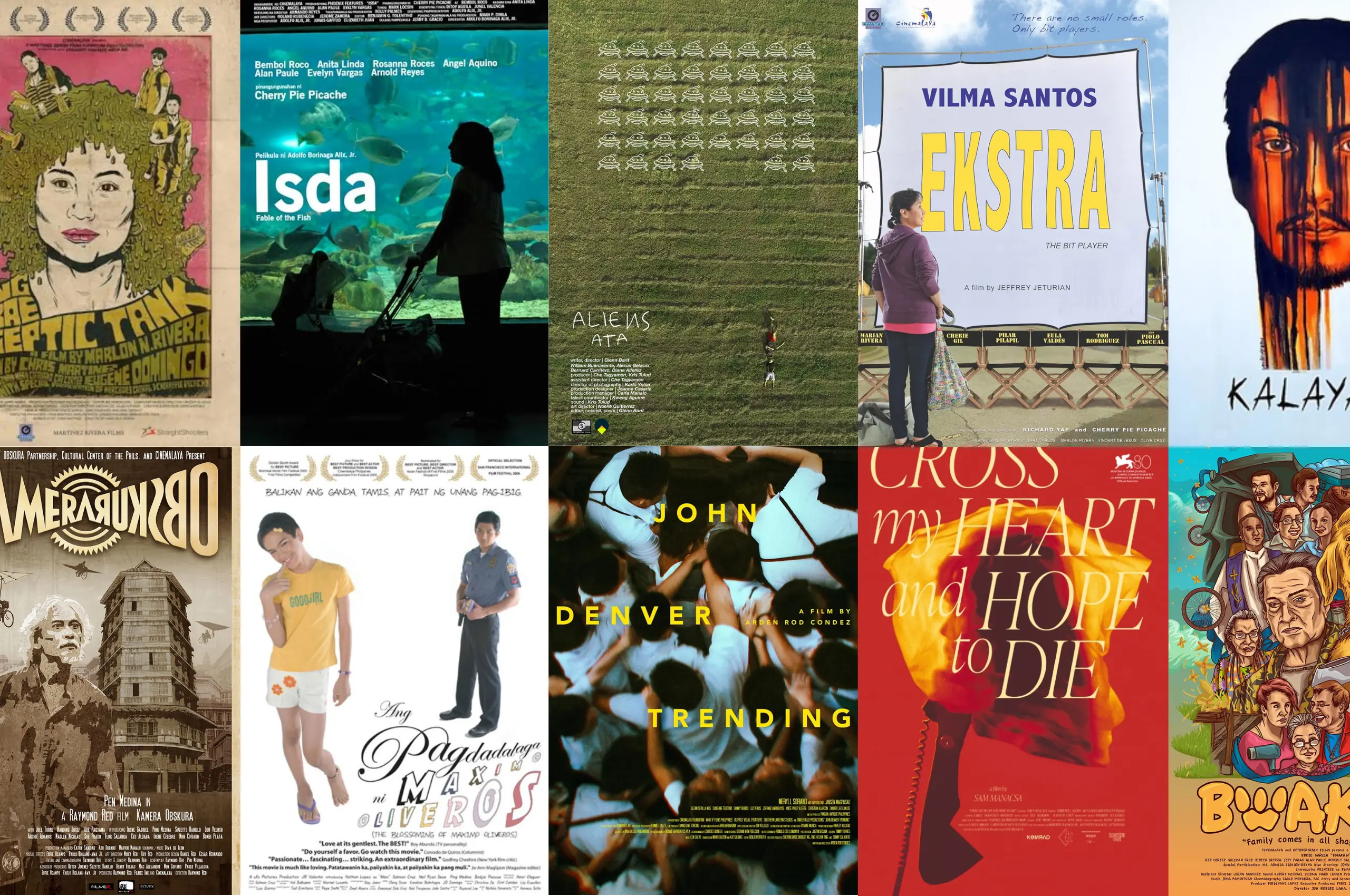

Cinemalaya offered us instant classics, such as Ang Pagdadalaga ni Maximo Oliveros (2005), Endo (2007), Engkwentro (2009), Mayohan (2010), Ang Babae sa Septic Tank (2011), Ang Sayaw ng Dalawang Kaliwang Paa (2011), Isda (2011), Bwakaw (2012), Sana Dati (2013), Ekstra (2013), Dagitab (2014), John Denver Trending (2019), Edward (2019), and Alipato at Muog (2024). Some of which went on to become local box-office hits and earn wide acclaim at the world’s top film festivals, including Maximo Oliveros’ three awards at the 2006 Berlin International Film Festival, and Engkwentro’s double wins at the 2009 Venice International Film Festival.

Cinemalaya has given us an effective formula: Its idea of independent filmmaking is one that is beholden to the modes and models of both alternative and commercial cinema.

The festival motored the careers of fresh and seasoned actors alike, from Jansen Magpusao (Best Actor for John Denver Trending), to LJ Reyes (Best Supporting Actress for The Leaving), to Lovi Poe (Best Actress for Mayohan), to Eugene Domingo (Best Supporting Actress for 100, then Best Actress for Ang Babae sa Septic Tank). Moreover, six Cinemalaya in-competition titles represented the Philippines for a shot at Oscar gold: Maximo Oliveros, Donsol, Septic Tank, Bwakaw, Transit, and Iti Mapukpukaw.

Above anything, Cinemalaya has given us an effective formula: Its idea of independent filmmaking is one that is beholden to the modes and models of both alternative and commercial cinema — alternative in the sense that it embraces alternative cinema’s guerrilla aesthetics and the revolutionary promise of the digital format, and commercial in the sense that its films’ shooting days, to some degree, still mirror the cost-saving “pito-pito” system notoriously done by Regal Films, and even Viva Films, in the ‘90s (only this time, Cinemalaya banks on “the Eddie Romero way,” a method that churns out supposedly more serious pito-pito movies, whose substance is on par with its craftsmanship despite the shoestring budget).

Read the rest of the story in the Arts and Culture issue of Rolling Stone Philippines. Pre-order a copy on Sari-Sari Shopping, or read the e-magazine now here.