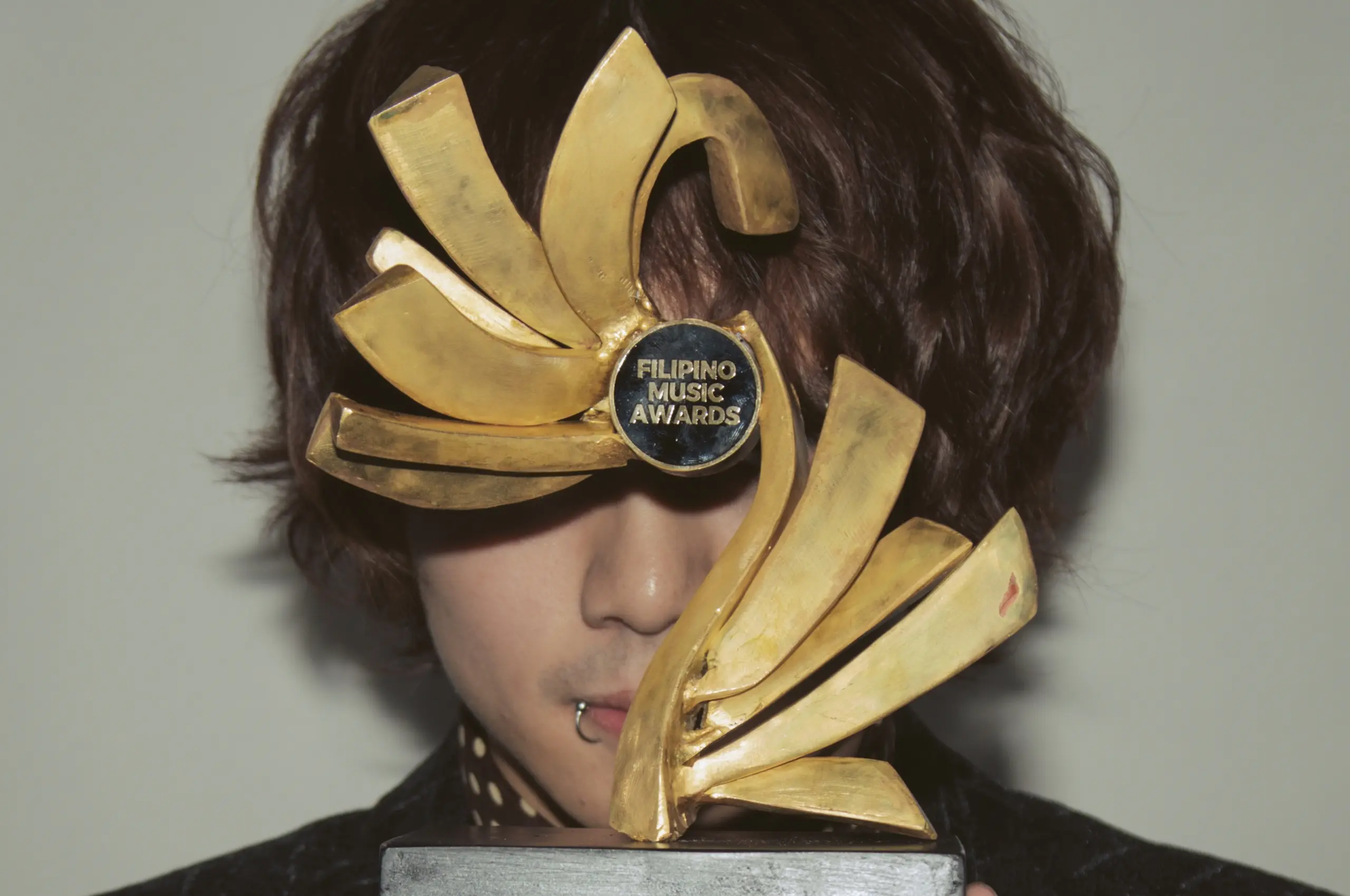

On October 21, the inaugural Filipino Music Awards (FMAs) honored some of the country’s biggest musicians for their impact on the country’s music industry.

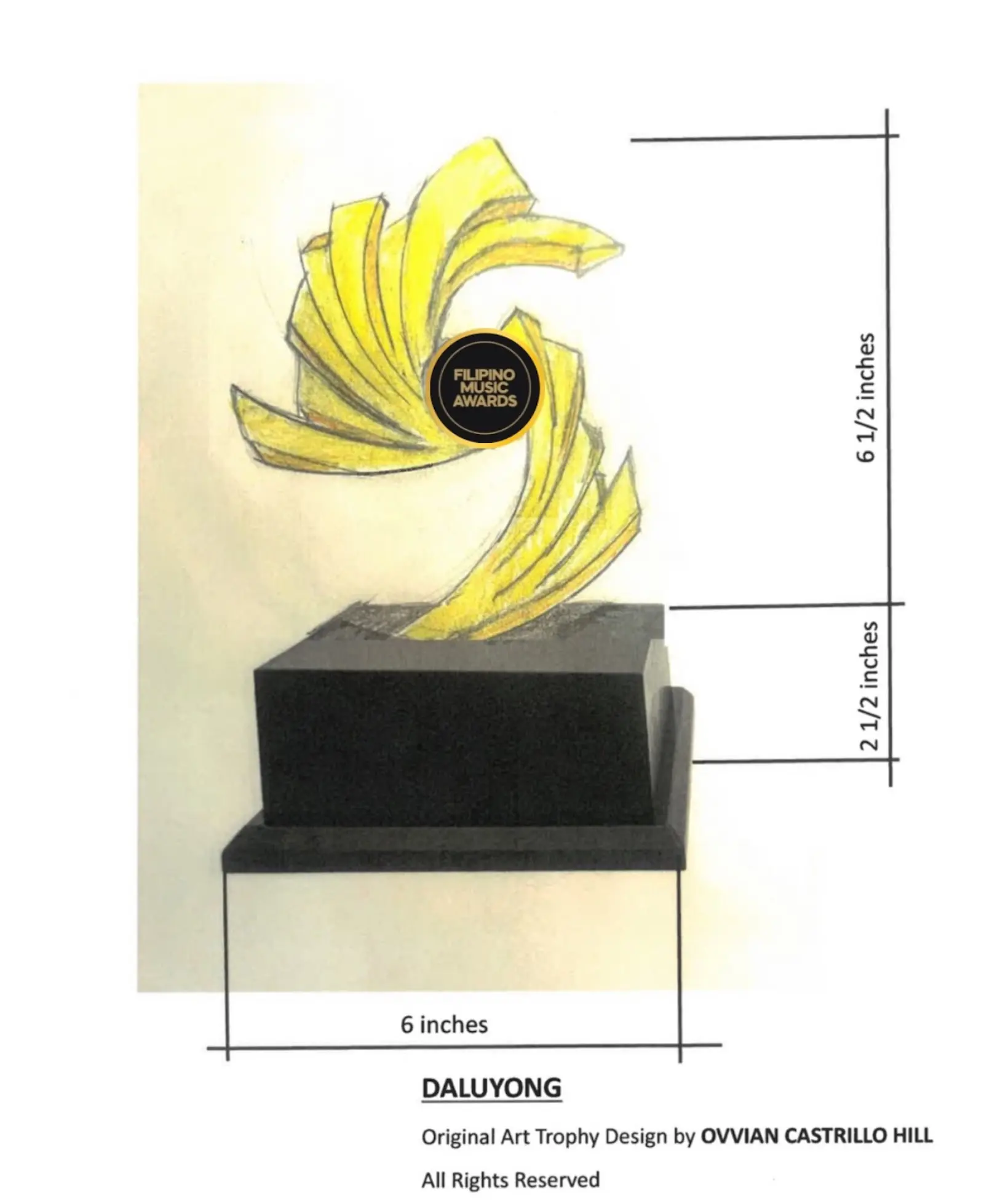

High-profile acts like SB19, Cup of Joe, and Morobeats walked the mainstage to receive their accolades, which came in the form of a uniquely designed trophy created by artist Ovvian Castrillo-Hill. From one angle, the brass sculpture takes on the shape of a brightly polished whirlwind. From another, it resembles a pair of fan-like leaves caught in the act of unfolding from one another. These shifts in perspective were, according to the artist, intentional.

“The word ‘daluyong’ was given to me during the designing stage,” Castrillo-Hill told Rolling Stone Philippines. “The daluyong is intended to depict how the awardees have disrupted the local music scene: they have so much power that they left an impact. At the same time, the anahaw leaves are meant to show the Filipino aspect of the awards.”

Castrillo-Hill specifically credited her background in design as a major influence driving this project. “Because I have a degree in design, I’m also trained to address a need,” she said. “I guess that differentiates design versus art, right? In this case, I needed to [find] the vision attached to the trophy, especially since the Filipino Music Awards are the first of their kind.”

A Family in the Arts

Since 2003, when she began sculpting under the mentorship of her father, the late and renowned sculptor Eduardo Castrillo, Castrillo-Hill has tirelessly honed her craft as a designer and artist. Beyond her skill in creating refined trophies, Castrillo-Hill has also created large-scale sculptural projects such as Shangri-La Makati’s 2003 Christmas tree installation, the Philippine Stock Exchange’s “Path to Prosperity” abstract sculpture, and the Land Form Obelisk in Fort St. John, British Columbia. She, along with her siblings, grew up under the tutelage of their father, who passed on his love for the arts to them.

“We grew up in the studio, literally,” said Castrillo-Hill. “In fact, in the later years, we lived in the studio like it was our home.”

However, she recalled how her father resisted pushing her towards a career in the arts. “I think it was more of how he kind of feared us having to work in his shadow,” she said. “So it was the protective nature of a parent. But my first opportunity to become a sculptor was because of my dad, and later on, [when] I told my dad that I was thinking of putting up my own studio… well, he said, ‘Why pa? Why not just do it in my studio?’ I took that as him wanting me to work alongside him in his personal studio, to use his tools and his equipment. For me, that was enough testament to his support.”

More than two decades after finding her way as a sculptor, Castrillo-Hill noted how it is projects like creating the FMAs trophy that fill her with a sense of familial pride. Although she is now based in Canada, the artist felt that it was important that her family studio in Cavite, led by her brother Mierro, make the trophies.

“To be perfectly honest, I was so excited,” said Castrillo-Hill. “Even the potential of making it was exciting to me. I knew it would be the first and it would be held by some of the biggest acts… and I’m such an SB19 fan. In my head, I was already thinking, ‘Oh my God, if they win, they’re going to be holding this trophy.’”

“The thing is, everything and anything that I do, I do for my family,” continued Castrillo-Hill. “I do things kind of thinking in the back of my head, ‘Someday, I want my grandchildren to see this.’ With this trophy, I’m hoping that generations down the line, my family can look at photos of it and say, ‘Oh, my lola made that.’”