From grief and corruption to politics and faith, horror works best when it feels a little too real. The most effective scares don’t just make us jump; they hold up a mirror to our collective fears.

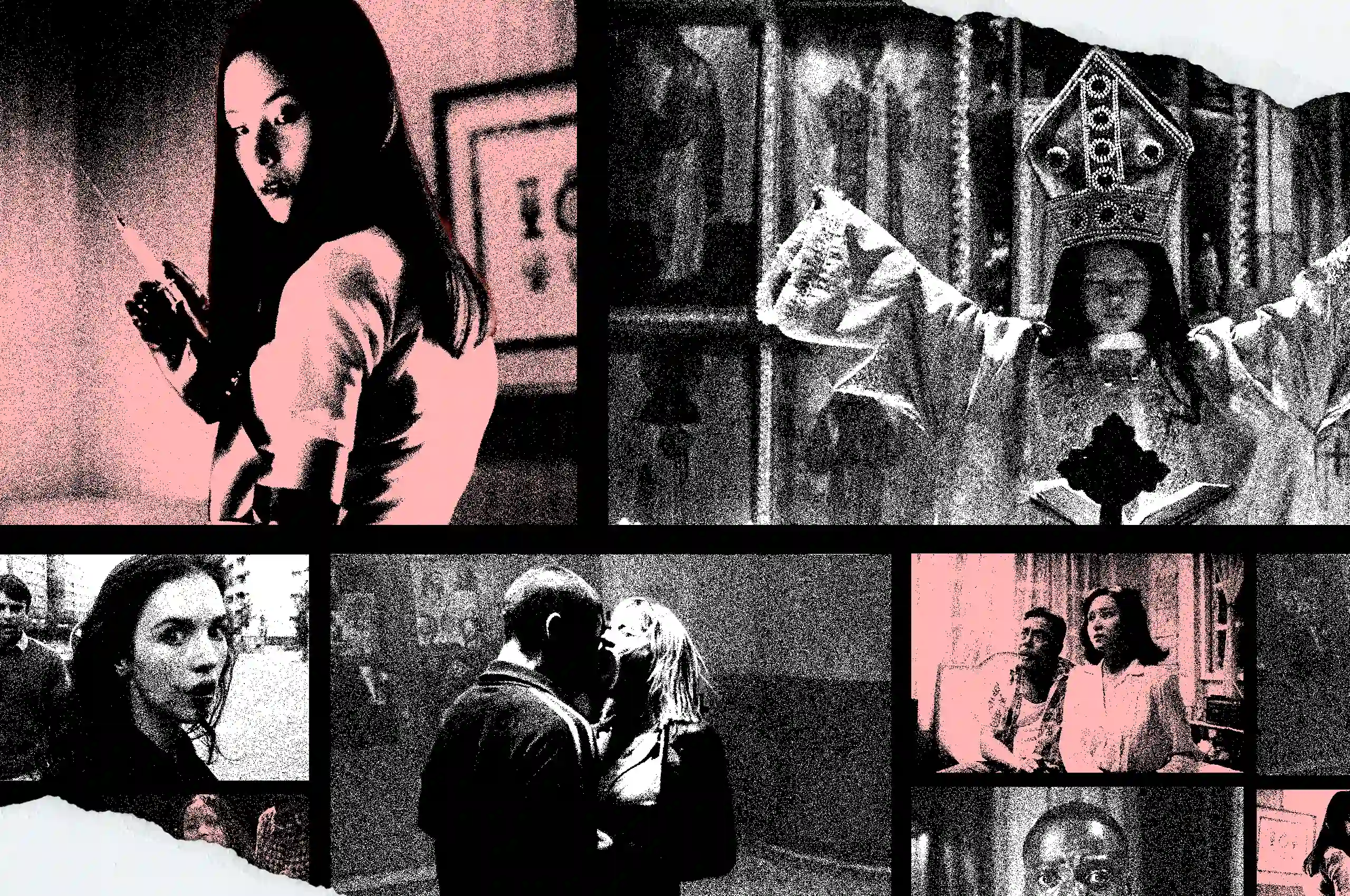

From Itim’s slow unraveling of family secrets to Audition’s brutal revenge fantasy against misogyny, Martyrs’ unsettling reflection on blind faith and The Thing’s paranoia in isolation, many horror films illustrate how truth is what scares us most. In this list, Rolling Stone Philippines gathers some of those films that linger long after you’ve left the theater and follow you home — and everywhere else in life.

You can follow Rolling Stone Philippines on Letterboxd.

‘Itim’

Mike de Leon’s take on Gothic horror, sprinkled with family trauma

Although Mike de Leon once wrote off his directorial debut as a mere “ghost story by a first-time and untested director from a wealthy family,” Itim is far from your typical horror feature. It opens with Teresa (an innocent-faced Charo Santos in her debut role), her mother Aling Pining (Mona Lisa), and a medium holding a séance, only to discover that Teresa’s missing older sister, Rosa (Susan Valdez), is dead.

From there, the movie pivots to the perspective of Jun (Tommy Abuel), an ambitious photographer from Manila, back home in Bualacan to visit his mute, paralyzed father, Dr. Torres (Mario Montenegro), and take photos of Holy Week rituals for his magazine. Jun and Teresa cross paths, but he soon realizes that something is deeply wrong with Teresa. De Leon excels in evoking dread, uneasiness, and atmospheric horror as he slowly reveals the true story behind Teresa’s downfall. —Mel Wang

‘Haze’

A claustrophobic hell-hole

Shinya Tsukamoto, who created the cyberpunk fetish horror Tetsuo: Iron Man, directs and stars in the mysterious 49-minute Haze. His character wakes up in a small concrete space, bleeding from his abdomen, with no recollection of how he got there. He aimlessly navigates the maze in an attempt to escape and meets a woman who helps him piece this puzzle together.

This film is hell embodied: scenes are shot in tight, dark spaces and spliced together in a way that is ambiguous and leaves the imagination running wild. The sound design — like when Tsukamoto’s jaw is locked tight on a rusty pipe with no space behind him to move — is also incredibly unnerving. If you’re claustrophobic, then maybe you should pass on this. But at its core, Haze is about being stuck in your own thoughts, and what happens when you’re blind to what is around you. —Sai Versailles

‘Sukob’

An excellent case against cheating

Chito S. Roño’s 2006 film Sukob weaves Filipino superstition with real-life anxieties about family, fidelity, and fate. When brides Sandy (Kris Aquino) and Diana (Claudine Baretto) fall victim to a deadly wedding curse, the film unravels a web of secrets linking their families. Roño grounds the supernatural in a domestic tragedy, using the sukob superstition as a metaphor for the inherited curses that haunt many Filipino households. For all its jumpscares and ghostly apparitions, Sukob endures because it exposes the horror of love, duty, and family expectations that bind just as tightly as a curse. —Pie Gonzaga

‘The Thing’

The horror of extreme isolation, plus some paranoia on the side

It’s never an ideal situation to be in Antarctica, trapped in a research facility, with an increasingly paranoid team of researchers and a grotesque, dangerous mutant that absorbs the biological make-up of any man or animal it crosses paths with. But alas, such is the case for our seemingly doomed group of intrepid heroes in John Carpenter’s creature feature, The Thing.

Shock and horror unfold in very quick succession. The body horror of The Thing is so freakishly real that the movie stands as one of the defining examples of what you can do with a little plaster, fake blood, and practical effects. But once you get past the mutated bodies and melted corpses (please don’t barf), we have this brutally realistic story of what happens when a bunch of people are left isolated and forced to try and survive. —Mel Wang

‘Noroi: The Curse’

Highly documented horror right before your eyes

If The Blair Witch Project invented the language of found footage, Japan’s Noroi: The Curse perfected it. Directed by Kōji Shiraishi in 2005, the film unfolds as a mockumentary following a journalist (Jin Muraki) investigating a series of supernatural events tied to a demon called Kagutaba. Rather than relying on quick scares, Noroi builds tension through realism: long takes, grainy VHS aesthetics, and slow, methodical pacing that mimic actual documentary work. Beneath the supernatural horror lies a social undercurrent about forgotten traditions, media exploitation, and collective denial. Shiraishi’s film feels like watching a tragedy unravel in real time, its realism making it almost unbearable to watch. —Elijah Pareño

‘Martyrs’

The cost of dying for what other people believe in

Notorious for polarizing audiences for its transgressive violence, Martyrs was the result of director Pascal Laugier’s period of clinical depression, being inspired to “make a movie about pain.”

Martyrs follows Lucie Jurin (Mylène Jampanoï), who, with the help of her friend Anna Assoui (Morjana Alaoui), seeks those who abducted and tortured her as a child. Their bloody journey sees them go through great lengths to seek revenge, and it is a depraved story about blind faith, and at what cost we are willing to die for a perceived collective good.

With that, the film invites strong references to the systematic abuse of children within the Catholic Church, and how this abuse can be hidden under the cloak of spiritual consequence. —Sai Versailles

‘Possession’

How obsession leaves us possessed

Possession is not your typical possession film. Directed by Polish filmmaker Andrzej Żuławski, the 1981 psychological horror drama is set in West Berlin and sees the breakdown of a marriage between Anna (Isabelle Adjani) and her husband Mark (Sam Neill), who is an international spy. After asking for a divorce, Anna begins to exhibit strange behavior, like disappearing from their house in the middle of the night for days, leaving their child alone and unkempt.

But it gets stranger. Anna has a secret lover, Heinrich (Heinz Bennent), who is clearly more charismatic than her husband. In a heated argument back in their apartment, Anna cuts her throat with an electric knife. She hides out in a dank ass apartment and makes love in a pool of blood and pus with a tentacled creature, which transfigures into a doppelgänger of Mark with green eyes.

The many incidents that unfold in Possession leave more questions than answers, but arguably, the “possession” explored here is the one we have for each other, and how it can manifest the worst parts in ourselves. In his 2009 book The Pleasure of Pain of Cult Films, Polish critic Bartłomiej Paszylk also explains how the film’s metaphor of divorce is a vehicle for exploring a disintegrating country. “[Żuławski’s] additional intention might have been for the Berlin wall to symbolize the Iron Curtain, and for Germany to symbolize Poland, a country he had to leave in order to keep making movies,” Paszylk says. —Sai Versailles

‘Audition’

A cautionary tale on why you shouldn’t objectify women (I mean, duh)

At a time in our history colored by the remnants of the #MeToo Movement and the rise of right-wing, alpha male rhetoric, there’s a lot to resonate with in director Takashi Miike’s torture porn, date-night-gone-wrong horror show, Audition. Released at the turn of the century, the movie centers on the newly widowed Aoyama (Ryo Ishibashi), whose teenage son Shigehiko (Tetsu Sawaki) urges him to find a new wife to be happy again. The most obvious solution, at least according to Aoyama, is to hold a fake audition to find his ideal woman: young, hot, and submissive.

Aoyama meets Asami (Eihi Shiina), who initially seems to tick off all of the widower’s boxes. Unfortunately, Asami proves to be vengeful, vindictive, and way too handy with a wire saw. What ensues is a torturous, but perhaps important, lesson for Aoyama on objectification and gender equality. —Mel Wang

‘The Babadook’

Five stages of grief right at your doorstep

Jennifer Kent’s 2014 psychological horror film The Babadook became a sleeper hit for good reason. The film follows widow Amelia (Essie Davis) and her son Sam (Noah Wiseman), who are haunted by a shadowy figure from a mysterious children’s book. The monster, The Babadook, becomes a symbol of Amelia’s buried grief and mental collapse. What makes the film terrifying is not the creature itself but what it represents: a parent’s slow surrender to depression and loss. Kent’s direction keeps the focus on the emotional toll of grief rather than capitalizing on jumpscares, turning personal despair into something almost supernatural. The film’s horror lies in recognizing that the pain it depicts could belong to anyone. —Elijah Pareño

‘Nanny’

A visual treat that blends psychological drama, colonial terrors, and folklore

This astonishing directorial debut by Nikyatu Jusu blends psychological drama, colonial terrors, and West African folklore, harkening back to the real-world horrors depicted in Ousmane Sembène’s 1966 film Black Girl, in which a young Senegalese woman flees to France in the hopes of a better life, only to be indentured to her colonizers. In Nanny, Senegalese immigrant Aisha (Anna Diop in a powerful performance) works for a white family taking care of their daughter while longing to be with her son, whom she left in her homeland.

This 2022 Sundance Film Festival Jury Prize winner distills visual imagery to illustrate how danger creeps up so suddenly around Aisha — and not just with the spectral forces that besiege her psyche in a foreign land, but also the actual manifestations of danger that surround her day-to-day life. —Don Jaucian

‘Get Out’

Meeting the family is never easy, but Jordan Peele takes that anxiety to the extreme

Your paranoia of white people will increase a thousandfold after watching Jordan Peele’s insane, hilarious, and deeply disturbing directorial debut, Get Out. Although the movie opens with a Black man getting kidnapped in a WASP-ish neighborhood (poor LaKeith Stanfield!), the main storyline follows Chris (Daniel Kaluuya), a Black man traveling to upstate New York with his white girlfriend Rose (Allison Williams) to meet her family.

Before things get batshit crazy, a lot of the movie’s horror comes from Peele’s ability to play with the awkwardness, discomfort, and terror of having your interracial relationship be scrutinized. Rose’s dad, Dean (Bradley Whitford), makes a point of telling Chris he voted for Obama. Her mother, Missy (Catherine Keener), turns her teaspoon menacingly in her teacup, fixing her gaze on Chris. And, despite trying to be friendly with the family’s Black groundskeeper and housemaid, Chris can’t seem to shake the feeling that something’s off with them. By the time the family’s all-white party guests come to visit, we’re just as on edge as Chris, because things are about to go very, very wrong. —Mel Wang

‘Kisapmata’

Domestic dictatorship has never been more terrifying

Kisapmata is one of Philippine cinema’s most chilling depictions of domestic tyranny. Based on Quijano de Manila’s “The House on Zapote Street,” itself inspired by a real familicide case, the 1981 film follows Mila Carandang (Charo Santos) and her parents, dominated by her ex-police father, Dadong (Vic Silayan). Inside their cramped, oppressive home, De Leon crafts a slow, claustrophobic descent into madness, not through ghosts or monsters, but through patriarchy, paranoia, and control. What makes Kisapmata especially unnerving is how it mirrors the national mood under the dictatorship from which the story is written: a home ruled by fear, secrecy, and unchecked power. —Pie Gonzaga

‘Seklusyon’

A Filipino horror story on the questioning of blind faith

As Filipinos, we do love a miracle. But in Erik Matti’s 2016 horror Seklusyon, it feels as if we shouldn’t be trusting the stoic, brooding, miracle-performing child Anghela (Rhed Bustamante) so quickly. The film, which bagged Matti Best Director at the 2016 Metro Manila Film Festival, centers on Miguel (Ronnie Alonte), a seminarian just on the precipice of entering the priesthood. When he and three other seminarians are tasked with secluding themselves for a week in a convent, chaos quickly unfolds when Anghela and her menacing caretaker, Sister Cecilia (Phoebe Walker) join them in their seclusion. Matti navigates the darker roots of Catholicism and questions the strength of our faith in the face of evil. —Mel Wang

‘Shutter’

Some photos should never be developed

The 2004 Thai horror classic Shutter, directed by Banjong Pisanthanakun and Parkpoom Wongpoom, helped cement Southeast Asia’s reputation for psychological horror steeped in guilt and karma. The movie follows a young photographer, Tun (Ananda Everingham), and his girlfriend Jane (Natthaweeranuch Thongmee) after a hit-and-run accident leaves them haunted by an apparition that appears in photographs. What begins as a simple ghost story turns into a moral reckoning. Each apparition and blurry image forces Tun to confront what he has done in the past and what he has chosen to ignore, leading to the movie’s shocking climax (Beware of back pains!). Shutter uses the spectacle of spirit photography not as a one-off gimmick but rather as a reflection on how the dreadful guilt clings to those who refuse to face it. —Elijah Pareño

‘The Blair Witch Project’

The found footage pioneer

Few films have changed the shape of horror as profoundly as The Blair Witch Project. Released in 1999, the movie defined the ‘found footage’ genre. Presented as recovered tapes from three student filmmakers who went missing in the woods while investigating a local legend, the movie blurred the line between fiction and fact. Its minimalist production and handheld camerawork created a realism that audiences weren’t prepared for. The terror stemmed from absence — never seeing the ‘witch,’ never knowing what truly happened. The film’s viral marketing and word-of-mouth mystique made it a cultural phenomenon, turning its low-budget format into a new kind of horror storytelling that thrived on imagination and paranoia. —Elijah Pareño

‘The Exorcist’

A perfect exercise in show, don’t tell

The Exorcist endures as the template for nearly every Catholic possession horror film since its release in 1973. Regan MacNeil (Linda Blair), after developing odd symptoms like levitating and speaking in tongues, is examined by two Catholic priests who conclude that she’s possessed by the devil. An exorcism ensues, forcing a poor film audience to witness an innocent 12-year-old girl endure one unsettling scene after another, like her head twisting to the back of her neck, or masturbating with a crucifix.

Beyond the religious references that director William Friedkin sought to exploit — and the disgust he aimed to provoke among Catholic viewers (a trick I admit I’m not very privy to) — what makes The Exorcist truly terrifying is the disorienting primal fear it taps into, one that comes from the unexpected, and that I was only able to confront through a kind of self-inflicted exposure therapy of repeatedly watching the film itself. —Sai Versailles

‘Paranormal Activity’

Novel for its time, scarily prophetic today

Oren Peli’s Paranormal Activity takes the found-footage format popularized by The Blair Witch Project and turns the cookie-cutter modern home into a site of surveillance and dread. Shot on a shoestring budget and presented through an assembly of static CCTV footage, the 2007 film follows a young couple, Katie (Katie Featherston) and Micah (Micah Sloat), as they document strange events in their suburban home. Here, the real horror lies not only in what you see, but also in what you anticipate, tapping into our tendency for dread in tension. There’s also Micah getting an Ouija Board despite having been warned about the evil presence haunting Katie. Believe women, Micah!

Beyond its supernatural premise, Paranormal Activity also captures the unease of a world increasingly mediated by cameras. In the age of oversharing and self-surveillance, the film’s haunting feels almost prophetic. —Pie Gonzaga

‘The Substance’

When you’re never enough

Coralie Fargeat’s body horror The Substance sees Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore) fade from the limelight as she grapples with the weight of age and irrelevance. She resorts to a black market drug to create a “younger, more beautiful, more perfect” version of herself (played by Margaret Qualley), with side effects that, with each dose, peel back the skin (quite literally) of her actual self.

Cinema is inundated with films that depict women’s bodies through the gaze of men, and we’ve come a long way to fix that. Yet, the way Fargeat depicts this twisted side of the female gaze feels equally needed, because it’s a sick reality that many of us grapple with and are conditioned into enduring. In this cruel world, it is, at times, an unfortunately necessary precursor to figuring out who you truly are. The Substance is highly cynical, yet incredibly real about the absurdity of self-judgment, and the death drive that separates us from what we really desire. —Sai Versailles

‘Creep’

When awkward silence becomes deadly

Patrick Brice Creep strips horror down to its most personal and claustrophobic form. Shot like a home movie, it follows Aaron (Patrick Brice), a videographer hired by an eccentric man named Josef (Mark Duplass), who slowly reveals himself to be unhinged and dangerous. What starts as awkward comedy spirals into psychological terror, carried entirely by Duplass’ disarming charm and eventual menace. The fear comes not from gore but from proximity. The horror of realizing the danger you’ve welcomed into your home. Creep turns social unease into a weapon, showing how easily trust can become fatal. —Elijah Pareño

‘Hereditary’

Toni Colette delights and scares as a mother

Hereditary begins as a story about grief and inheritance but spirals into something far darker. When the Graham family loses their secretive matriarch and a child, miniaturist Annie (Toni Colette) begins to uncover a legacy of trauma that is psychological and supernatural, affecting her teenage son Peter (Alex Wolff). Beneath its occult trappings, the 2018 film captures the horror of being unable to escape one’s family, genetics, and fate. Here, writer and director Ari Aster renders generational trauma as literal, inescapable possession. —Pie Gonzaga

‘Climax’

Why you should never leave your drink unattended

Climax is a trip, and I’m not sure if it’s the good kind. Directed by France’s film provocateur Gaspar Noé, the psychological horror follows a dance troupe as they celebrate the last day of rehearsals with an after-party. Held in an abandoned school gym in the dead of winter, the night starts off great; the music’s popping, and everyone’s getting loose.

Then suddenly, the vibes stop vibing. People start bugging out, and they realize someone’s spiked the sangria. Climax is a whodunnit on acid — literally — as its characters navigate a good time turned drug-induced psychosis. It’s a night gone wrong, and the thought of irreparably losing your mind overnight, or being roofied against your will, is a fear that, for anyone who has gone to a nightclub, doesn’t feel too far from reality. —Sai Versailles