Noni Abao’s Bloom Where You Are Planted has just become Cinemalaya’s first documentary to win the Best Film prize of the festival. The documentary distinguishes itself as the first feature-length docu among other winners that mix dramatic narrative and non-fiction, such as Richard Jeroui Salvadico and Arlie Sweet Sumagaysay’s Tumandok (2024). Bloom Where You Are Planted joins the ranks of this year’s Gawad Urian Winner, the Cinemalaya alum Alipato at Muog, as one of the most acclaimed documentaries to come from the independent film festival. Alipato at Muog won the Special Jury Prize at the festival last year.

Though social realist narrative films have always dominated Cinemalaya, it has recently included non-fiction films in its competition lineup, starting with She Andes’ drug war docu Maria in 2023. The aforementioned Alipato at Muog competed in 2024, chronicling the search for Jonas Brugos, who was forcibly disappeared in 2007. The film was made by his brother, JL. This year, Abao’s Bloom Where You Are Planted is the sole documentary in the competition lineup, where films by both established auteurs and emerging filmmakers vied for the festival’s top awards. Aside from Best Film, Bloom Where You Are Planted also took home the Best Editing award.

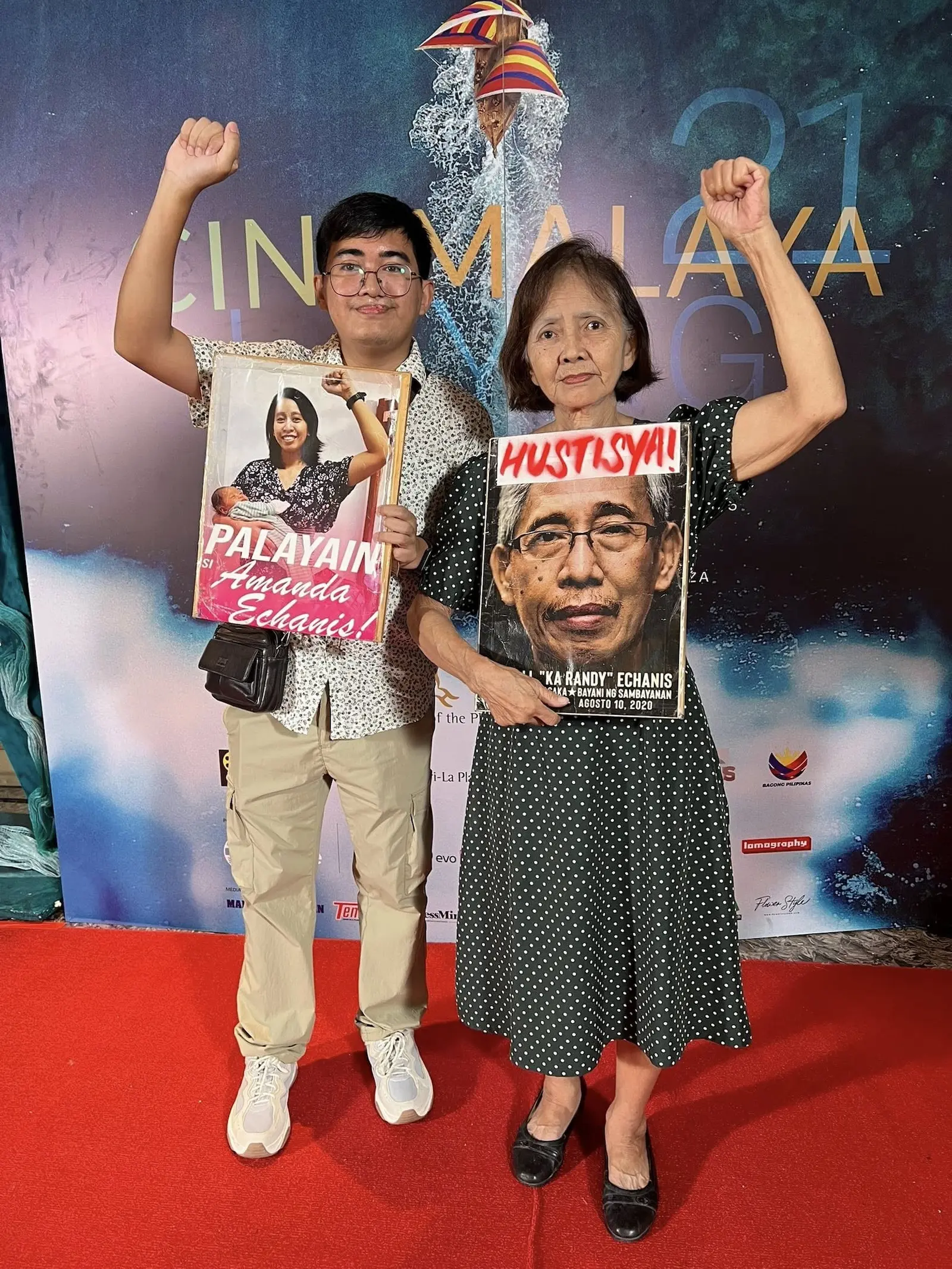

Bloom Where You Are Planted tells the stories of activists working in the Cagayan Valley and how the state has silenced their voices of dissent: development worker Agnes Mesina, jailed cultural worker and activist Amanda Echanis, and peace advocate Randy Malayao, who was gunned down in a bus in 2019. It was the death of Malayao, with whom Abao was close, that provided the spark for the film.

“Noong 2019, sa Active Vista Film Lab ng DAKILA, [ang] original title [ng pelikula] was Transients,” Abao told Rolling Stone Philippines. “Naka focus lang talaga dapat siya sa buhay ni Kuya Randy. Kasama ko si Joanne Cesario noong kino-cnonceptualize ‘yong film 2019 pa lang. Kakauwi ko lang from Cagayan, pareho kami ni Joanne na nagiisip kung itutuloy pa ba ‘yung pagkilos or magtatrabaho na lang. Doon namin siya nabuo. Pero noong pandemic, may napasukan ulit kami na isa pang film lab na nag-suggest na mag-add ng characters.”

This became an opportunity to tell more about the lives of activists working in the region.

“[Noong] 2022, nasa isang medical and relief mission kami sa Aparri, Cagayan with Ate Agnes, nang bigla siyang hinuli,” said Abao. “After noon ko mas na-decide na magandang hiwalay pa na story ‘yung kay Ate Agnes. Mas nag-make sense siya kasi sila ni Kuya Randy ay madalas din talagang magkasama noon sa mga campaign ng Cagayan Valley.”

“Si Amanda naman, importante for me ‘yung kuwento niya kasi siya ‘yung isa sa mga cultural worker at artista ng bayan na talagang lumubog sa masang magsasaka. Kaya noong submission ng Cinemalaya, silang tatlo ‘yong characters na nilagay ko sa concept.”

Bloom Where You Are Planted divides its stories into chapters, spending time with each of the subjects to expand their stories outside of their advocacies. In building the story of the film, Abao also credits editors Che Tagyamon and Arnex Nicolas. “As editors kasi kahit may script silang sinundan; sila pa rin ‘yung mga nag-suggest ng other parts na ilalagay. Kaya dapat sa documentary, ma-credit din as writers ang editors.”

This is Abao’s first feature-length film. His first film, Dagami Daytoy, which discusses the Didipio community’s struggle against large-scale foreign mining in Nueva Vizcaya, won Best Documentary at the 32nd Gawad CCP para sa Alternatibong Pelikula at Video.

In this interview, Abao discusses how the film was made over the years, the security measures taken to protect his subjects, his own experience with being red-tagged, and why land rights remain a crucial issue in the Cagayan Valley region.

I find it interesting that a collective, Taripnong Cagayan Valley, is credited as the producer of the film. Could you tell us more about the group’s efforts in producing the film and raising awareness about their advocacies in the region?

Taripnong Cagayan Valley is a Metro Manila-based organization ng mga Cagayan Valley advocates. ‘Yung meaning ng “taripnong” in Ilocano is assembly/gathering. Taripnong ‘yong nag-e-echo ng issues ng Region 2, mas lalo pa ng mga human rights violations na nangyayari doon pati na rin ‘yong campaign ng farmers doon. Malaking part ‘yong Taripnong kasi marami kaming members na iba’t-iba ‘yung profession, ‘yong maliliit na bagay na kailanganin namin sa shoot or sa prod, nandyan ‘yung members para sumalo. Taripnong rin ‘yung tumulong para magawa ko ‘yung short ko dati na Dagami Daytoy (This Is Our Land) about a mining affected community in Nueva Vizcaya.

“Isa sa mga hindi napaguusapan na issue na magandang mapakita sa film ‘yong mismong pagkakabaon sa utang ng mga magsasaka. Mahal na farm inputs, walang sariling lupa, kailangan umutang para makapagtanim.”

It’s also somewhat poetic that the injustices depicted in the film were particularly pronounced during the Duterte administration. Yet, he’s the one now charged with crimes against humanity at the International Criminal Court. But in the film, Randy’s friend said it was just one step towards justice. What did you feel about Duterte’s criminal case while you were making the film?

Long overdue na. Ang daming naging victims ng human rights violations lalo na noong Duterte regime sa Cagayan Valley. Isa ‘yung pagpatay kay Randy Malayao. Pero marami pang naging victims ng extra judicial killings: Ariel Diaz, Rogelio and Rolito Mendoza, Fr. Mark Ventura, Victorino Tesorio, Lolito Rasa, at napakarami pa. Kailangan niyang magdusa sa pagiging mastermind ng napakaraming killings noong panahon niya as a president.

Masuwerte pa nga siya kasi hinaharap pa siya sa korte. E paano sina Kuya Randy na binaril na lang basta sa bus habang natutulog? Pati na rin ‘yung iba pa na kahit alam nilang mga walang ginawang masama ay papatayin na lang basta. Malaking parte rin ng mga kaso niya ay ‘yung pagkaka-establish ng NTF-ELCAC [National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict] na naging source rin ng patung-patong na human rights violations sa buong bansa.

Noong 2018-2020, naging biktima rin ako ng “red-tagging.” Nagpakalat sila ng mga flyers na may mga mukha namin na may caption na mga terorista raw kami, pati na mga tarpaulin na may mga pangalan at mukha namin sinabit nila sa mga highway at interior barrios sa buong region.

One of the things I noticed about the film is that it remains cinematic, eschewing the TV documentary type of filmmaking. What were the choices in terms of filmmaking for Bloom?

Maganda lang din siguro ‘yung landscape ng Cagayan Valley. Bilang isang agrikultural na region, isa sa mga naging guide namin nina Steven [Evangelio] at Mike [Olea], [mga cinematographers ng pelikula] sa pag-frame ay gawing madalas wide ‘yung shots. Mas maliliit ‘yung mga tao or elements. Gusto sana naming mabigyan ng emphasis na sobrang lawak ng kanayunan, pero ‘yung mga magsasakang nandoon, konti o kaya mas madalas ay wala silang mga pag-aari na mga lupa.

Also, marami ring shoot days na ako lang talaga nag-shu-shoot. Kaya baka mas personal at dikit ‘yung framing sa ibang shots.

I’m guessing that accessing your subjects was difficult, especially Amanda, since she’s in prison. What were the ethical choices made to ensure their safety?

Kailangan kong dumaan sa napakaraming bagay. Pero mas doon ko rin na-establish sa mga subjects na ginagawa natin ‘to nang sama-sama. Hindi ko lang to pelikula, hindi lang ito pelikula ng prod team; pelikula natin itong lahat. Kinailangan naming magconsult nang napakaraming beses sa mga lawyers na tumulong sa amin from Sentro Para sa Tunay Na Repormang Agraryo (SENTRA), National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers, at Public Interest Law Center, para ma-ensure ang safety ng lahat. May mga inalis lang at nabago na treatment pero nagawan naman ng paraan, nagwork pa rin. Kasi siyempre bago ‘yung pelikula, kaligtasan muna.

In your director’s statement, it’s very clear that you were deeply embedded within the community where you chose to work. What were your safeguards in terms of bringing their story to the screen, making sure that they’re authentic, and that you were being responsible in handling the stories of their people?

Until now naman hindi pa rin naman talaga matatag ‘yung loob ko ‘pag naiisip ko kung dapat ba ako talaga ang gumawa ng pelikulang ‘to, or kung dapat ba ginawa ko pa ‘to in the first place. Pero kasi mas naiisip ko sila Kuya Randy, Ate Agnes, Amanda, at lahat ng mga pinagdaanan nila. Also noong nakapasok na rin sa Cinemalaya, during the film lab, isa sa mga pinagkakatiwalaan kong tao (si Joanne Cesario) na nakasama ko rin sa pagbubuo ng concept nong 2019, ‘yong hinihingian ko lagi ng advise. Kinakatok niya ako lagi kapag feeling ko ‘di na dapat ‘to gawin.

Pinabasa ko rin pala kina Ate Agnes at Amanda noon ‘yung parts sa script na gusto ko sana i-include sa story nila through their lawyers. Nagpapaabot sila ng feedback sa mga parts na ‘di sila comfortable. Ganun din kay Kuya Raymund Villanueva, pinabasa ko sa kanya before ‘yung part [niya] at hiningian siya ng feedback. Kaya mas napagtibay din ‘yong film.

One thing that the film highlights is that the Cagayan Valley actually produces a large volume of our essential agricultural products — and that land rights are deeply tied to this. Would you consider making another documentary expanding on this issue?

Sana! Isa sa mga hindi napaguusapan na issue na magandang mapakita sa film ‘yong mismong pagkakabaon sa utang ng mga magsasaka. Mahal na farm inputs, walang sariling lupa, kailangan umutang para makapagtanim. Gusto kong makagawa ng documentary na mas makakapag-explain kung bakit systemic ‘yung cycle na ito na nagreresulta sa napakaraming bilang ng agricultural workers sa isang region na may malawak na land area pero nahahati sa mga hacienda.

What are the plans for screening the documentary outside the festival?

Harapin muna natin yung MTRCB [Movie and Television Review and Classification Board]! Pero may mga naka-set na kaming screenings sa mga schools. Gusto namin siyang dalhin sa Cagayan Valley, sa mga sakahan at mga lugar na natulungan ng mga subjects. Pero dahil nga sa subject matter at security issues, baka medyo matagal pa.

The documentary is deeply emotional. How do you tread the line between evoking the proper emotive response and making sure you’re not sensationalizing the emotions of the story?

Babalik tayo sa katotohanan na tao naman tayong lahat. Puwedeng nanay ka, may anak, may bestfriend. Mahirap i-tread ‘yung line pero mas sa amin, ‘yung pagiging tao pa rin muna. ‘Yung bigat kasi ng pelikula, kung kilala mo silang tatlo, magiging emotional ka talaga. Pero para sa mga hindi sila kilala, kaya nagiging mabigat at tumatawid ‘yung pelikula dahil pare-pareho lang din naman tayong gustong mabuhay nang payapa at may dignidad; nangangarap na sana magkaroon ng isang lipunan na wala nang nanay na hindi makauwi sa anak dahil sa threats sa buhay niya, nanay na walang rehas na balakid para maalagaan ‘yung anak niya, saka isang kaibigan na kasama mo pa ring umuwi sa probinsya niyo kapag fiesta. ‘Yun ‘yung naging sandigan ng film namin.