Felice Prudente Sta. Maria first got the idea to write What Recipes Don’t Tell: Philippine Food History in Fifty Words in 2007, while making small talk with Nick Joaquin in the lobby of the Cultural Center of the Philippines.

After exchanging pleasantries, Sta. Maria, a heritage advocate, culinary historian, and established writer herself, found the courage to ask the National Artist for Literature why he’d once credited guisado as one of the most important Spanish contributions to Philippine culture. Joaquin was caught off guard and noted that he’d made the claim based on gut feeling alone. “Well, let me try to prove you right,” Sta. Maria promised Joaquin.

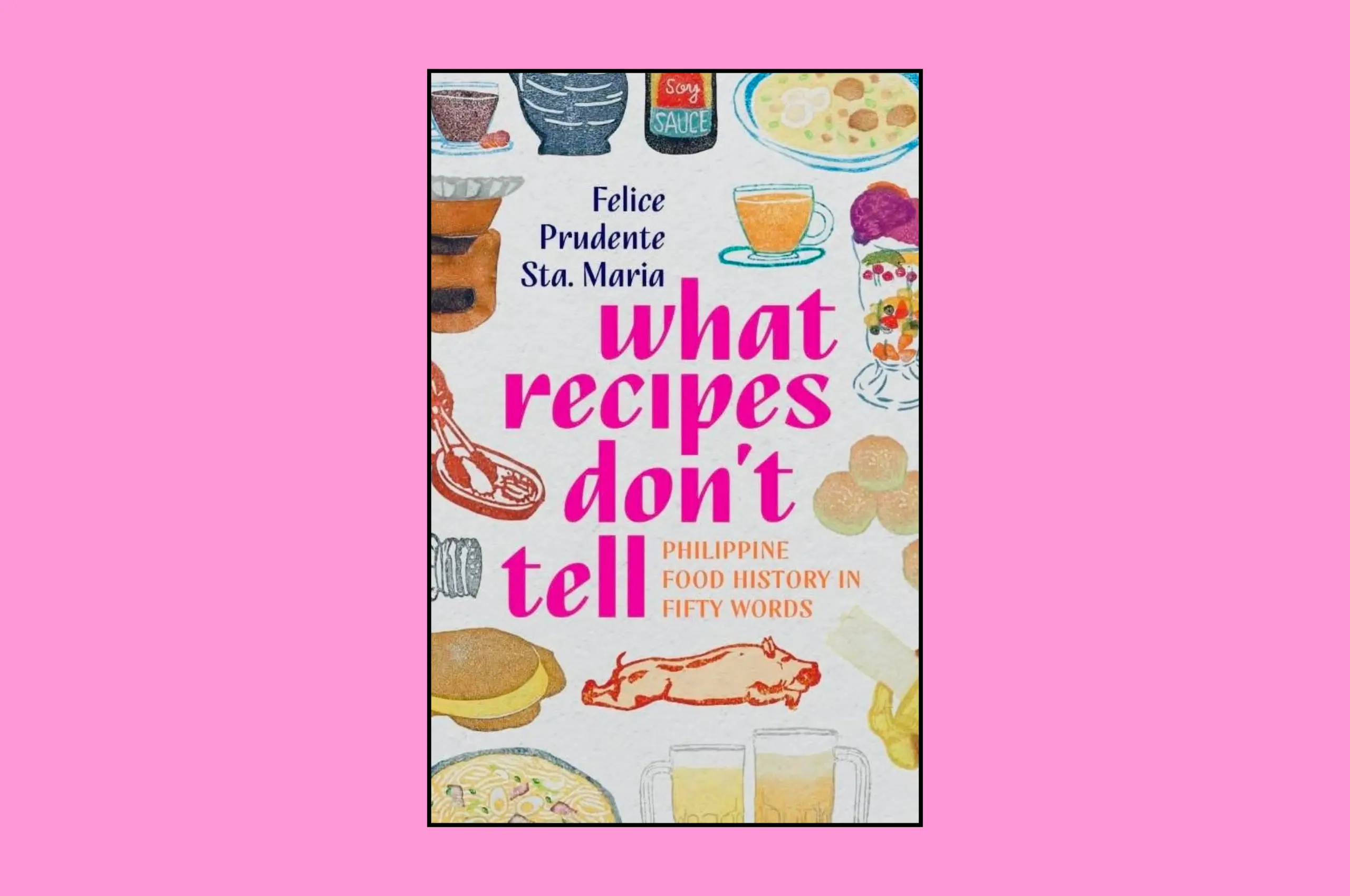

Nearly 20 years later, Sta. Maria has done just that with her latest collection of nonfiction essays that trace the history of our cuisine through the language we use to describe it. Published by Ateneo de Manila University Press, What Recipes Don’t Tell takes 50 Filipino culinary words — from guisado, to kilaw, to linamnam, to suka — and picks apart their origin stories.

For instance, on the topic of guisado, Sta. Maria details how the cooking method first stemmed from the country’s Spanish colonizers. Pedro de San Buenaventura, one of the Spanish friars who documented life in the young colony, noted that early Filipinos had never tried to “guisa” prior. “Guisado” came to encompass the act of cooking rice, frying, and sautéeing.

“Many Filipino dishes with pedigrees from Spain begin by making guisa,” wrote Sta. Maria. “In other words, lightly frying in a small amount of lard or cooking oil some garlic (a precolonial ingredient), tomato (introduced to Europe and Asia from Mexico during colonial times), and onion (either the precolonial scallion used all over Southeast Asian islands or the white onions brought during Spanish and American colonial times).”

Sta. Maria’s precision when it comes to describing the meals, cooking styles, and ways of eating in the Philippines extends to the rest of her essays in the collection. Whether she’s detailing the Los Baños process of preparing longganisa (which involves injecting pork thighs with a brining solution), or the 73 pancit makers of Parian in 1700, or the rise of the San Miguel Brewery as the only surviving beer-maker of the colonial period, Sta. Maria is meticulous when it comes to writing the history of our country’s food.

“If recipes could only talk,” she wrote in the book’s introduction, “they would tell us about the artisanal smartness needed to cook them, the saga to make their ingredients readily available, and the joy they elicit when appearing prepared at a meal. Recipes are clues to how individuals and a society have eaten at a point in time.”

What Recipes Don’t Tell is currently available for purchase via Ateneo de Manila University Press’ Shopee and Lazada.