Once upon a time, Quezon was going to be funded by Amazon’s Prime Video. It was to be a beneficiary of the streaming boom, a film funded by the general largesse provided by a multinational company trying to gain a foothold in the region.

This did not pan out. Prime Video decided that investing in the region wasn’t a great business decision after all. They shut down the whole division that was developing projects in Southeast Asia, leaving Quezon in limbo.

Producer Daphne Chiu waited three months to hear from Prime Video, which had told her that there was still a possibility that they might fund the film. She heard nothing from them, and set out to find funding on her own. And this was no easy feat. Filmmaking is just a tough business proposition these days. It is rare to hear about a local movie making any money. If they score a profit, it’s likely because their budget was low to begin with. Or they were made under the auspices of an existing streaming deal made back before that bubble burst. Or it might have benefited from being part of the Metro Manila Film Festival and managed to be the one film that year that people actually decided to see.

Quezon is none of those. It’s a movie that will have to make its money back in theaters, and that’s pretty dicey. Cinema attendance in general is down. Even big Hollywood movies are struggling to fill up theaters. The price of tickets is nearly twice what it was back when Heneral Luna became a word-of-mouth hit a decade ago, and it seems like audiences have decided that it makes more economic sense to stay at home and watch something on their phones instead.

Which then brings up the question: why make the film at all? “Because it’s the last,” Chiu says. “We started something. Sayang naman kung hindi namin tatapusin.”

Three movies were always the plan, though Tarog never assumed that he could get any of them made. Even Heneral Luna, which started this whole deal, was never a sure thing. “Originally sina Ed Rocha ‘yong nagsulat. And I just got permission to rewrite it. And I didn’t think na makakahanap ako ng pera for that. So, I just forgot about it.”

And then it just happened. “After I did Sana Dati, bigla na lang may pera, out of Fernando Ortigas’ whim. Never ko siyang ti-nake for granted, even after Luna, even with the scale of Goyo, [I never thought] ‘Yeah, we’re going to finish the whole thing.’ Before the pandemic when they asked me to write Quezon, at least the script, sinulat ko lang. Pero I was never really like, ‘Yeah magagawa ‘to.’ And then the pandemic happened.”

“With large-scale stuff, I’m never expecting to get it done. It’s not just with getting the funding. It’s… kung paano mo siya babawiin.”

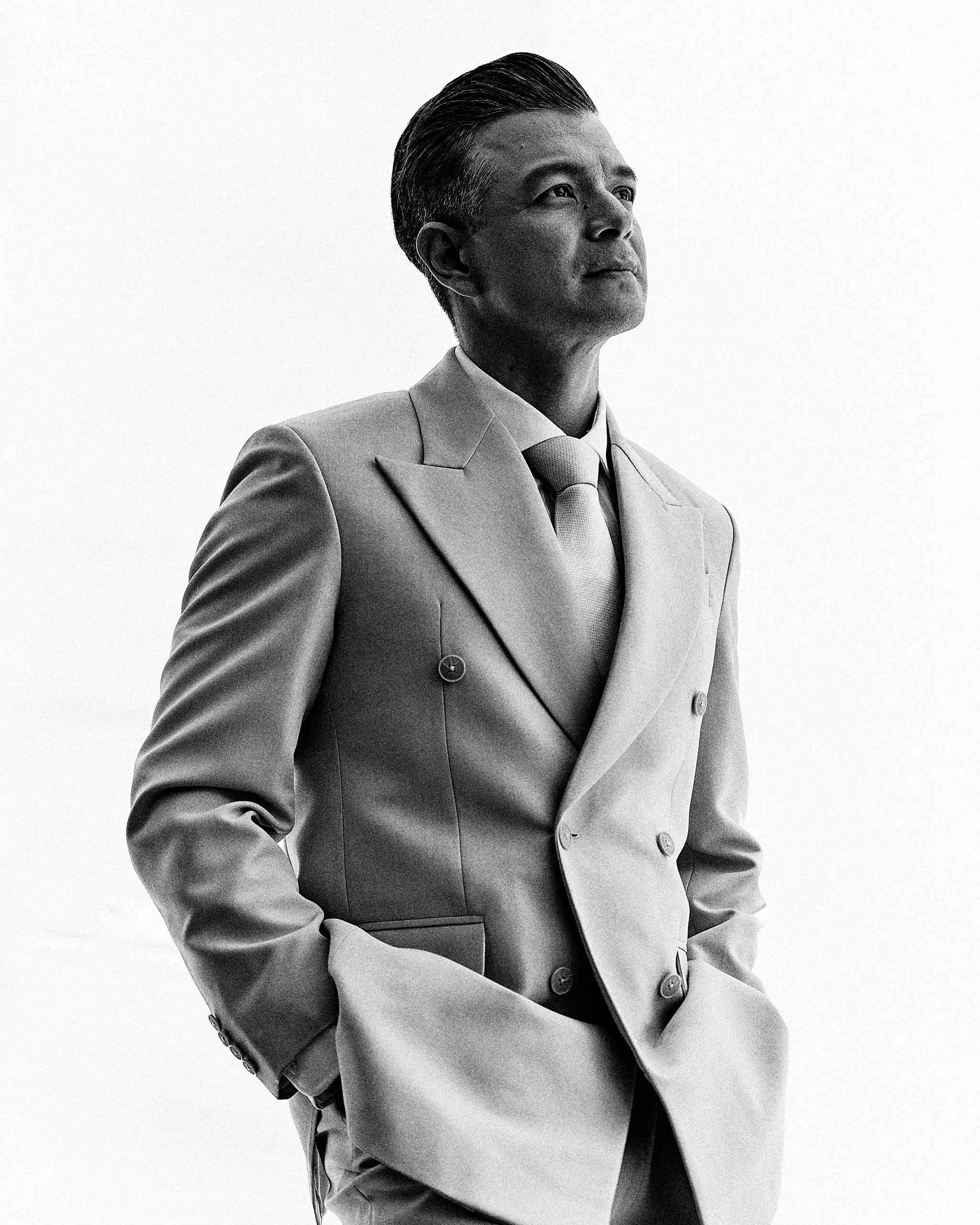

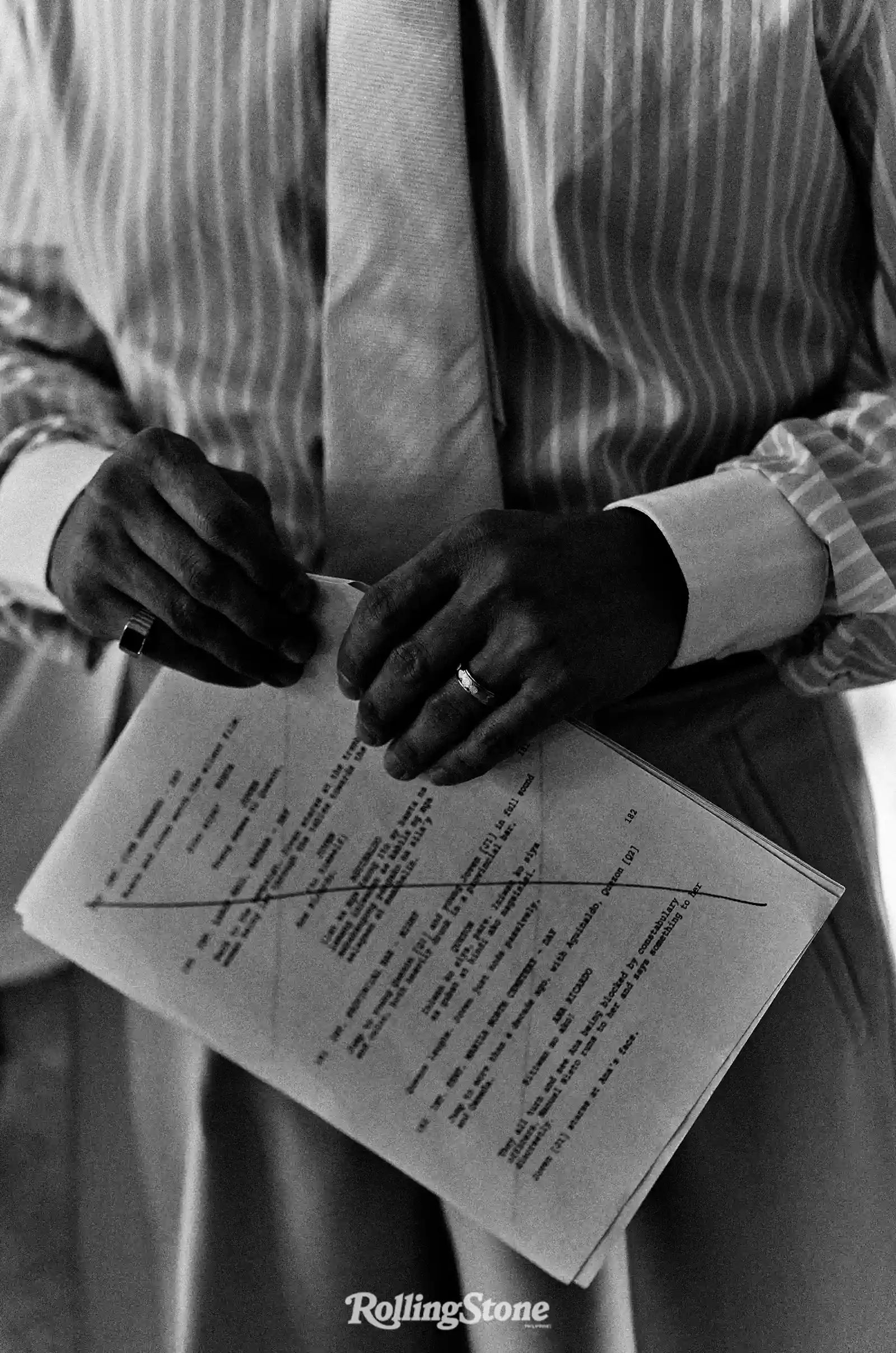

“The first version of the script was even more complicated,” Tarog says, owing to its complex subject. “With Quezon, pili ka ng decade. Ang daming pwedeng gawing pelikula tungkol kay Quezon.” He reportedly went through around 80 books, trying to get some sort of handle on this man who would negotiate our independence from the U.S., establish a national language, and build the country’s largest city and name it after himself. It was a lot of work, and even Tarog, who has experience getting large projects off the ground, didn’t quite believe that any of it would happen.

“With large-scale stuff, I’m never expecting to get it done. It’s not just with getting the funding. It’s… kung paano mo siya babawiin.”

When Chiu finally called him to say that she had found the money for him, he was already deep in developing another project. He had written a siokoy project for Lovi Poe, and was set to direct it. However, the money Chiu had raised came with a deadline. He had to do Quezon now, or it probably wouldn’t happen at all.

And so, he begged off the Poe project, and once again set off on producing something that would be infinitely more complex and difficult and time consuming. When asked if he ever considered telling Chiu that he couldn’t do it, he just shrugs.

“Kasi nandoon na ‘yong material. And to be honest, masaya ako doon sa script. Nandyan ‘yong pera. Why would I say no? It becomes a matter of ‘yon na ‘yong ipa- prioritize ko.”

He echoes Chiu’s sentiment. “Sinimulan namin e. Kailangan tapusin.”

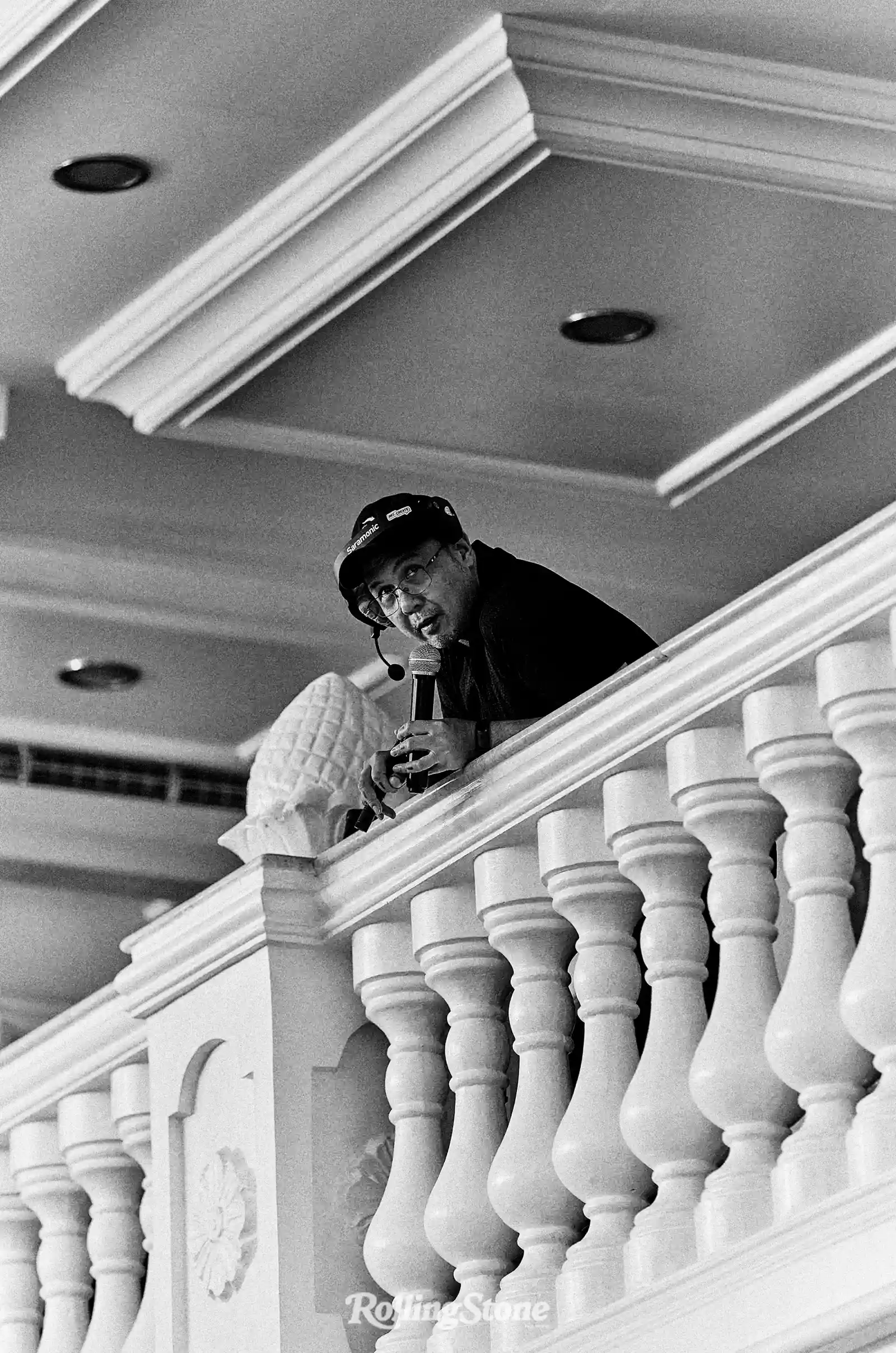

A little bit of personal history: the only other time I’ve been on a Jerrold Tarog set is Senior Year. This was in 2010, and the film was about a group of graduating students faced with all the dramas that come with the idea of having to leave the comfort of high school. He had a cast of non-professionals, all of them students at the school, which also happened to be the setting for the movie.

It was the kind of scrappy production that was kind of common back then. It was shot on one camera, at times operated by Tarog himself. This was part of the value proposition of Tarog as a filmmaker: he could take on many roles in the production. He wrote. He edited. He composed music.

He would soon be working with Regal Films, directing a couple of segments of the venerable horror anthology series Shake Rattle and Roll, as well as the remake of Peque Gallaga’s 1992 film Aswang. This was the landscape like back then, with the grant-giving festivals becoming a sort of developmental league for the more commercially minded studios. Although the industry wasn’t exactly super profitable at the time, there was a sense of optimism that created opportunities for younger, hungrier filmmakers.

“[Quezon] is the last [in the Bayaniverse series]. We started something. Sayang naman kung hindi namin tatapusin.”

And then Heneral Luna happened. The film’s success remains an aberration. Historical films don’t make money: they cost too much, and the public never seemed particularly inclined to learn about the past through cinema. However, word of mouth would turn it into a phenomenon, despite theater owners trying to boot it out of their cinemas within the first week. Its success would fuel, for at least a little bit, the upstart production company TBA Studios, which would go on to make various other bids at mainstream success. Nothing, though, would come even close to replicating the impact of Luna, not even its sequel, Goyo.

But Tarog’s cachet in the industry would remain, and he would be selected to head up the new Darna project over at ABS-CBN. And this would go beyond the one project: he would be spearheading a crossover universe of komiks properties that would be our version of the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

And then, ABS-CBN went away, a casualty of a government run by a strongman bearing a grudge.

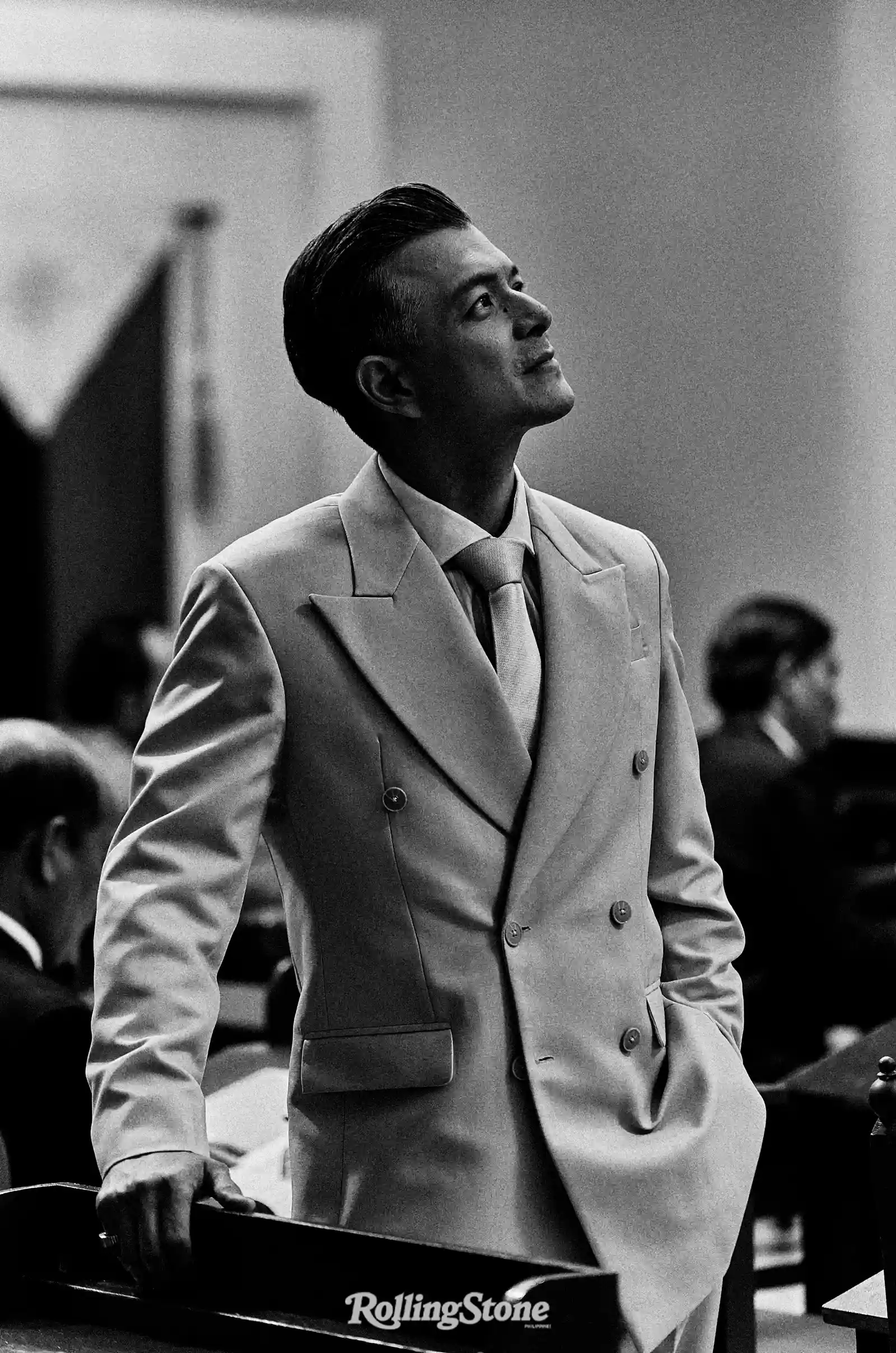

Read the rest of the story in The State of Affairs issue of Rolling Stone Philippines. Order a copy on Sari-Sari Shopping, or read the e-magazine now here.