TikTok has become the internet’s most powerful time machine. The platform’s algorithm has made it easier for songs from decades past to resurface, especially those from the fringes of the alternative scene.

Take the English rock band Bôa from London, whose song “Duvet” has been edited into video snippets of the anime series Serial Experiments Lain alongside clips of emo kids posing in front of the mirror, showing off their latest fits. Bôa vocalist Jasmine Rodgers discusses TikTok’s reviving effect in a Reddit Q&A in the r/indieheads subreddit. “Really grateful that TikTok has become a platform for music – one wholesome aspect,” she says. “We’re seeing the digital turn into the physical when people actually come to the shows, sometimes their very first shows.”

Recently, the track “QKTHr” by Irish electronic music legend Aphex Twin, from his 2001 album Drukqs, has been used in “corecore” videos of juxtaposed imagery set to emotionally somber music, conveying the overwhelming condition of modern digital life in the 2020s. From a music history perspective, tracks like “Duvet” and “QKTHr” are not even remotely close to one another, yet TikTok makes them feel like they’re neighbors living on the same street.

In recent months, users have rediscovered under-the-radar Filipino acts like Eggboy, the lo-fi slacker rock project of Pedicab vocalist Diego Mapa; there’s also the early aughts power pop act Juana and alternative rock trio Fatal Posporo, looping over nostalgic or meme-fied life moments. What were once cult favorites passed around in burned CDs during small gigs, or uploaded on long-forgotten Web 1.0 blogs, are now soundtracking fifteen-second videos to millions of users on TikTok, or what some call “snack content.”

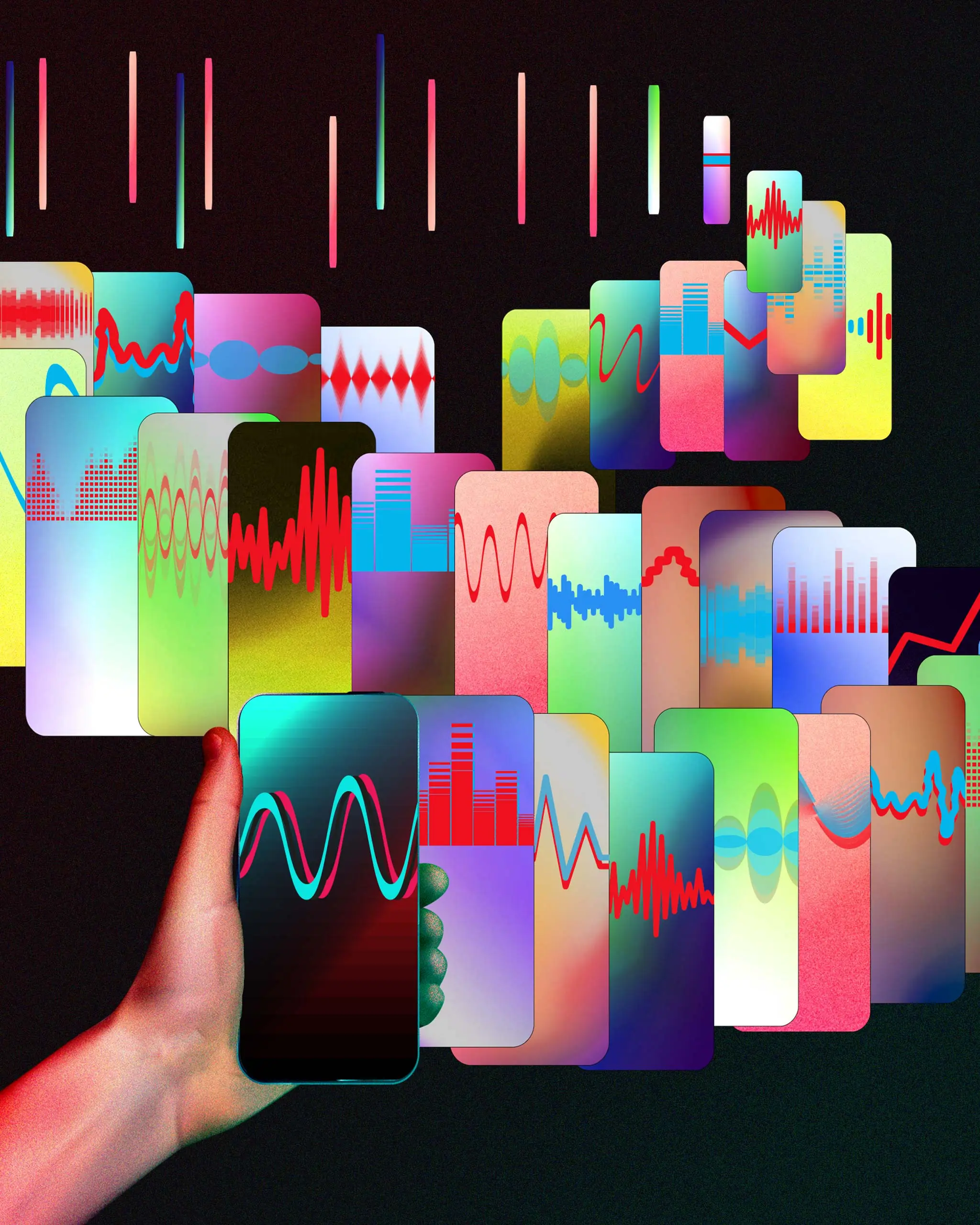

This renewed attention has little to do with the artists themselves promoting their work. Instead, it comes from how TikTok’s algorithm rewards rediscovery. A song’s life cycle on the app no longer depends on radio play or playlist placement, but on how well it fits into an endlessly remixable stream of content to snack on or consume. Users pluck fragments of old songs — a chorus here, a bassline there — and incorporate them into their own aesthetic language. The algorithm picks up on repetition, pushing these sounds further into feeds until they become trends in their own right.

Unlike Instagram Reels, which favors polished content from established communities you’re connected to, TikTok’s recommendation system thrives on virality and unpredictability, exposing users to content from creators they’ve never seen before. That openness has made it easier for forgotten, niche music to find entirely new audiences on TikTok, turning obscurities into overnight sensations.

‘FYP’ Rabbit Hole

In this new environment, alternative music has found an unlikely second home. The once rigid lines between indie and mainstream blur when Eggboy’s 1998 track “Nagsasawa Ka Na Ba?” is paired with vintage footage tied to indie film studio Furball and its throwback projects like Tales of the Friendzone and Strangebrew. The hooks and melodies that never fit the commercial mold now find relevance among a generation raised on snippets and samples. In doing so, TikTok has redefined what “discovery” means. Instead of digging through vinyl crates or scrolling through obscure music forums, young listeners encounter Filipino alternative songs through the randomness of TikTok’s For You page, where a track’s virality depends not on its label backing but on how well it captures a mood.

Similarly, Juana’s song “Reyna ng Quezon City” about making ends meet in Metro Manila’s biggest city has become the soundtrack of ukay-ukay hauls and slice-of-life montages. Juana was a short-lived band that released only one album, Misbehavior, in 2006. They don’t have dedicated pages on online music databases like Discogs or RateYourMusic; the only remaining detail of their existence outside of TikTok is their copy-pasted bio from their now-defunct band website, which is accessible via the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine.

@missmariestella reyna ng quezon city #fyp ♬ original sound – mariesteller

The song’s resurgence shows how TikTok users have reimagined “Reyna ng Quezon City” as an anthem for self-expression — an aesthetic marker for people navigating city life and embracing independence through fashion, humor, and irony. Still, this strange recycling has given Filipino alternative music a longevity it never had before. More recently, on October 4, actress Maris Racal even went on to cover the song with an acoustic guitar on a bathtub.

Fatal Posporos’ 1999 song “Sili Song” has also found new life on TikTok; its rough charm and homemade sound stand out in a feed crowded with hyper-produced pop snippets. Lately, users have been looping it in ironic anti-day job edits — a strange but fitting recontextualization of a song that was originally about boredom and infatuation. Its resurgence captures how nostalgia is used to reframe older material into users’ own language. What once existed as Manila’s indie quirk now plays out as part of a moodboard culture that prizes imperfection, sincerity, and the thrill of rediscovery.

With artists like PinkPantheress and Addison Rae finding their fame on TikTok, the platform’s chokehold on global music discovery is hardly new. Yet, its power to rewrite history feels different when applied to music that exists outside commercial systems. The rediscovery of bands like Eggboy, Juana, and Fatal Posporos reflects a larger shift in how Filipino music history circulates online with listeners reclaiming them from obscurity. What resurfaces isn’t random, but guided by the algorithm’s knack for pattern recognition.

For artists who once operated in small, fragmented scenes, TikTok is proving that it isn’t just a virality machine; it is also an archive — a gatekeeper of memory.