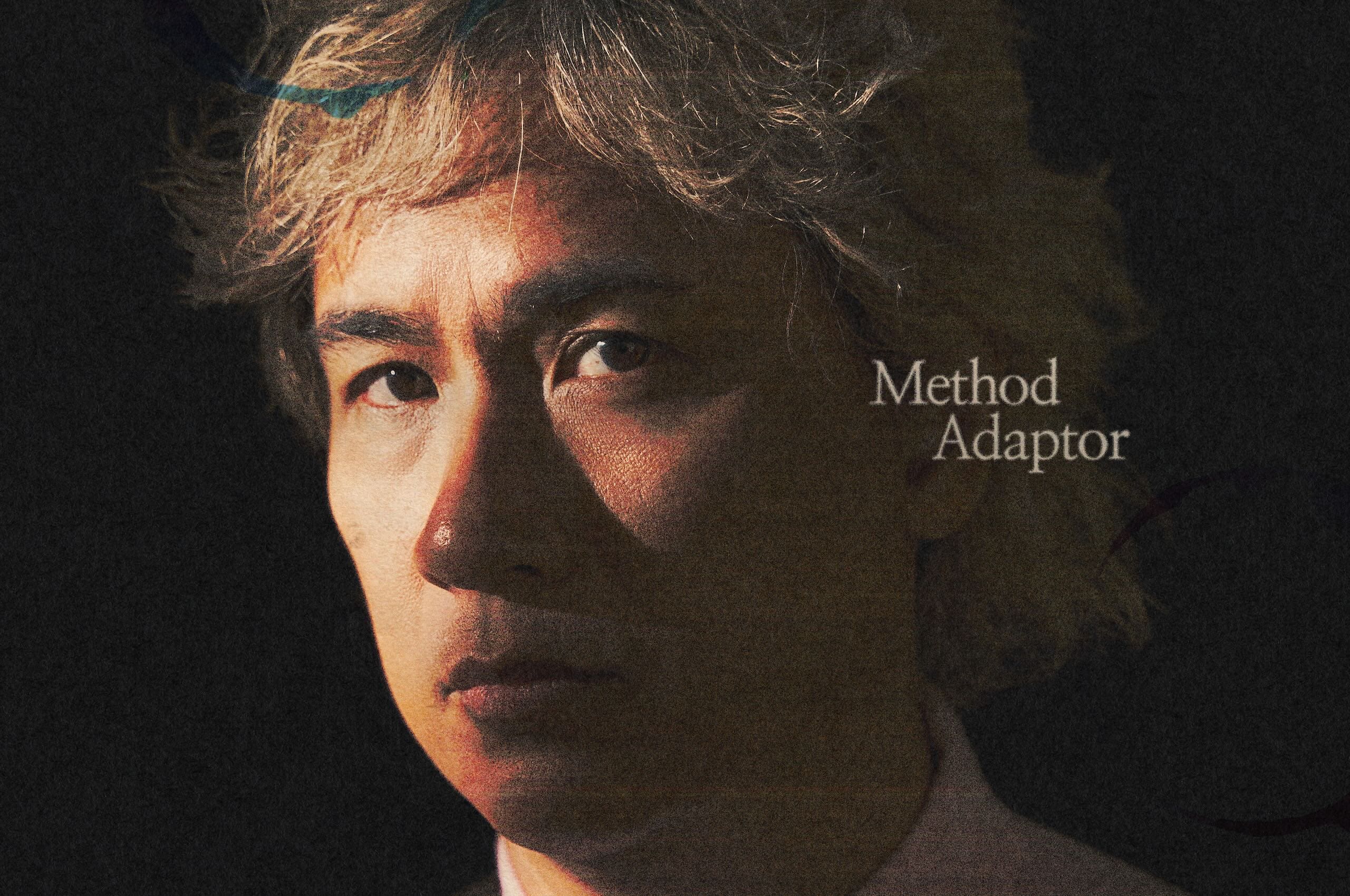

“Please don’t judge me if I wanted to take some credit for myself this time,” Ely Buendia said at the listening party for his newest outing, Method Adaptor, which he curiously identified as his “official” first solo album. Wanted Bedspacer, released at the turn of the century, would only count as his “unofficial” solo debut, as far as he’s concerned. He reasoned that it was just the product of “toying around,” downplaying it as a deliberate career move on his part.

Yet the perennial frontman and Pinoy rock kingpin bristled at the possibility that after all is said and done, even if he had built such an extensive catalog or an unassailable legacy, he won’t even have his own name on the marquee. All-time favorites like “Magasin” and “Ang Huling El Bimbo” might be simply marked as pages from the Eraserheads songbook, even though that was the very band that had turned him into a household name. Years of duties, too, for Apartel, Pupil, The Oktaves, and The Mongols — count being a label boss for Offshore Music as well — had made him “all banded out,” he quipped.

However, Method Adaptor doesn’t read anything like an all-consuming preoccupation just to blow up his name from the tiny liner notes to 96-point type on the cover. Far from that, truly, and that would just be an unfair accusation. Think of it as him facing the not-so-final boss in the game that has been running for more than three decades and counting.

“I haven’t established myself as a songwriter or a solo artist,” he plainly pointed out, with just a bit of urgency. “The stakes for me have never been this high since the recording of Ultraelectromagneticpop! It’s like a make-or-break thing for me.”

Inspiration though, is a fickle thing. And sometimes, even if it does come in like jolts or in waves, it’s not the right or timely kind. So, for his latest act, Buendia turns to Marlon Brando, that debonair icon of classic Hollywood.

Well, sort of.

Buendia said he named the album as wordplay on “method actor”, referring to the performance philosophy and technique where actors would embody even the inner lives of their characters — sometimes, to great extremes. In other words, the actor completely becomes the character. Many Hollywood actors had delved into that approach: Cate Blanchett, Christian Bale, Meryl Streep, Joaquin Phoenix — the list goes on.

All great actors have always grappled with a key conundrum: “Did an actor need to feel a character’s emotions in order to represent them, or should emotions be represented without being felt,” a New Yorker piece put it. For method actors who champion the former, their psychic arsenals run deep. This was the approach that roughly resonated with Buendia. “I’ve always been fascinated by the processes of those actors,” he said. “The foremost example of which is Brando… These guys actually go through something. They have their ritual to create a performance.”

“I think that also reflected on how I started writing and coming up with the whole album. It’s to dig deep — deeper than I’ve ever dug in a while to make something meaningful,” he added. “I just asked myself, who am I right now? What are the things and ideas that I like? What are the issues and emotions that I feel I can speak meaningfully about?”

As the prelude to the 10-track opus, “Faithful Song” is a striking and disarming incantation. Here, Buendia takes on a wispy, harrowing lilt in a sort of elegy for his late mother (I somehow recall Mount Eerie here), but as if a caveat, that’s the only specific he’s willing to spell out.

The kinetic centerpiece “Kandarapa” (one of two tracks recorded at the storied Abbey Road Studios) is economical with its words, but bends and turns with a melodic force that’s unmistakably Buendia (personally speaking: a little like Broken Social Scene). But as he sings, “Bumibilis ang panahon / Anong araw na ba ngayon,” (Time is running fast / What day is it today, anyway?) there seems to be a certain gravity bringing him to his own knees. After all, this is not — in his own words — “a young man’s album” anymore, but much about that sense of urgency is left to everyone’s speculation.

Who’s this and that song about, you might ask. “Bulaklak sa Buwan” speaks like an indictment of demagogues, but also any other peddler of untruths and broken promises. At the midpoint with “Deadbeat Creeper,” Buendia draws on his own scorn for the titular anonymous character with lurid detail yet remains cleverly obtuse about it: “There’s a special place in hell for scourge like you.”

Buendia (in)tends to be opaque with the finer details. Allegories, if there are any to begin with, are never meant to be fully interpreted. You can try, but where’s the fun in that if he would need to explain or decipher everything for you. “I don’t really put the microscope on me and analyze myself. I just don’t do that,” he says, so just let it all percolate.

Method Adaptor simply isn’t — and doesn’t read — like an exercise in autobiography. Neither is it a chronicle of vivid (sometimes spicy) anecdotes nor a narration of musings. Buendia won’t engage in the trade of blind items, anyway. He’s not out to make us privy to his own secrets or expose his vulnerabilities, if any of us were looking out for those. This is not the time and place — at least for now, maybe.

We might never know the specifics of the material Buendia is working with in Method Adaptor, but the ambiguity might as well be the point. When he says he wants to convey thoughts about “dealing with life overall,” he likely has never intended the songs to be a tell-all of his life so far or any single episode, even. Buendia offers his perspective, however: “You can surrender to it or you can fight. You know, ‘Rage, rage against the dying of the light,’ basically.”

There are no hints of the prolific Buendia just showing off his formidable musical range either, even with the record’s most whimsical-sounding fare (“Kontrabando” with its neon-tinged synths and “Tagpi-Tagping Piraso”) side-by-side with his anthem-loving proclivities on full display (“Tamang Hinala,” “Sige,” and the defiant epilogue, “Esprit de Corpse”). He favors a taut edit than eclectic patchworking — or maybe once again, like in Wanted: Bedspacer, experimentation.

This is no proverbial reinvention. He isn’t breaking character, so to speak. Throughout it all, Buendia isn’t after developing a new sonic vernacular for himself. There are flickers of “Disconnection Notice,” modern rockers Pupil’s eminent hit (and my personal favorite), through the electric surges of “Sige,” “Bulaklak sa Buwan,” and “Tagpi-Tagping Piraso” (Try imagining Glaiza de Castro’s frenzied dystopian Tinikling, as in the music video, set to these pieces). “Deadbeat Creeper” and “Chance Passenger” are bluesy pitstops with traces of an Oktaves jam. And of course, E-Heads is E-Heads. Each melodic hook, Buendia’s strong suit, echoes far beyond Kalayaan. The quartet’s legacy infuses the ink by which each line is scribbled.

The perennial frontman writes in the language of his own mythos. But even in a familiar terrain, he scrupulously forages for emotional truths deeper than ever before — “digging around his garden of decay,” to borrow from “Esprit de Corpse” — until he’s satisfied. With barely any commentary, this oeuvre is a sprawl of metaphors that thrive in paradoxes: plainspoken but shrewd, impenetrable but expressive, well-timed but far from novel — yet all lucid, befitting a 54-year-old sage.

This is the narrative we just have to live with and respect: he’s not doing this to please anyone but himself. And that’s perfectly fine, but if it all resonates with anyone, then that’s great. He knows himself best, and this is just what it means for him to be honest with himself. He’s unflinchingly guarded with good reason, without sabotaging his own efforts.If anything, Method Adaptor broadens the horizon for Ely Buendia, artist and songwriter. There are a myriad possibilities here, just like the penultimate track “Chance Passenger” puts it: “Give me a chance / I wanna show you / That I could be the kind of man / That you could want.”