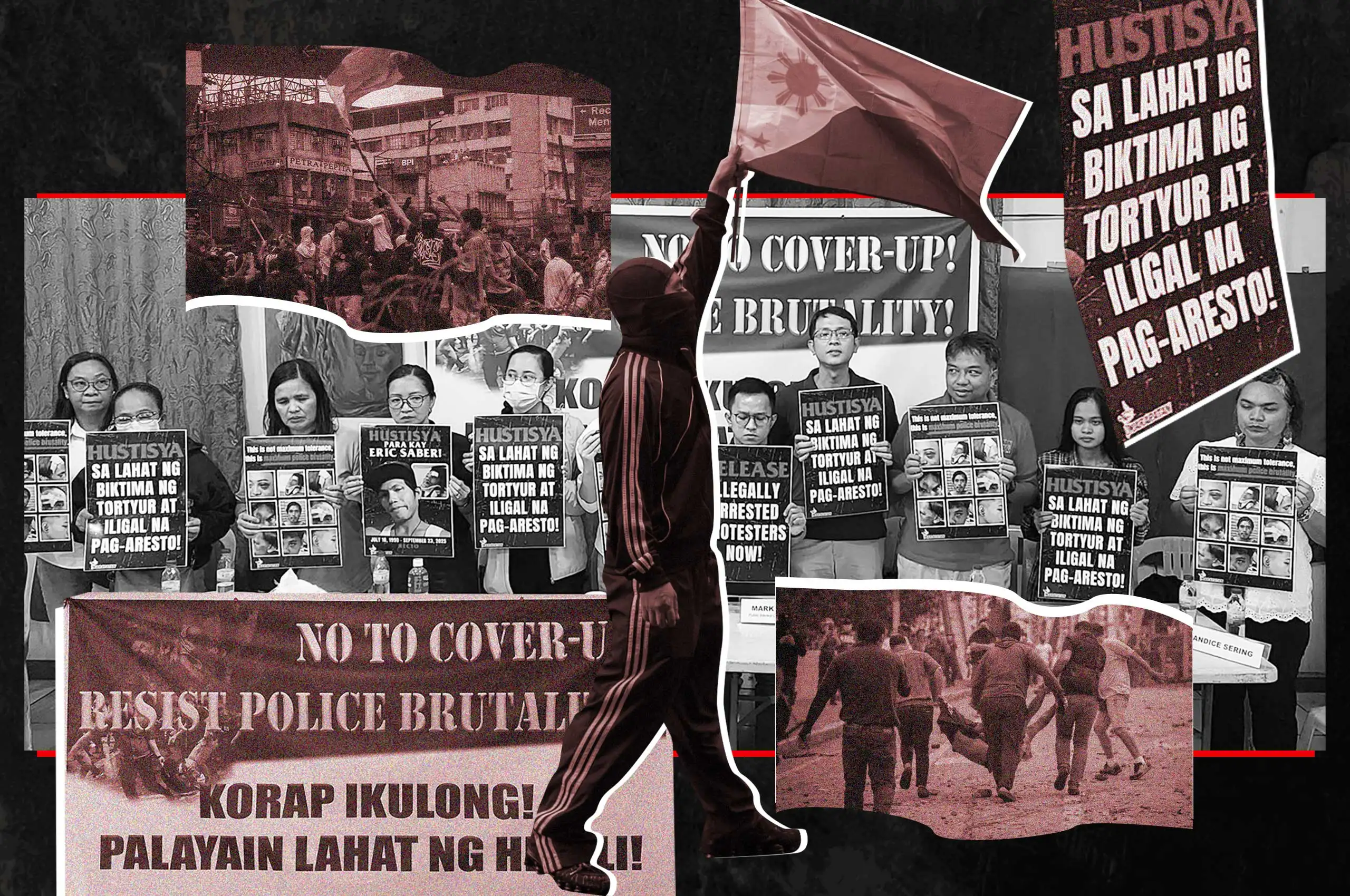

In the past week, human rights groups and lawyers have called for the release of the “Mendiola 216,” the collective name given to the individuals, many of them minors, arrested and detained by the Manila Police District (MPD) following the riots on Sunday, September 21, in Mendiola, Recto, and Ayala Bridge in Manila. The calls intensify now as these groups and lawyers share evidence and reports of abuse and substandard conditions in the MPD headquarters and other stations.

Authorities maintain that there were “zero casualties” from the scuffle between police and citizens on September 21. Interior Secretary Jonvic Remulla and Manila Mayor Isko Moreno both commended the police for exercising “maximum tolerance” for protesters, with the Philippine National Police (PNP) claiming that no tear gas and guns were used.

Several witnesses, however, reportedly saw otherwise, with police using tear gas and water cannons to disperse the crowds. “The tear gas was the absolute catalyst of the chaotic outbreak,” Loyola, one of the protesters at the scene, told Rolling Stone Philippines. “Everyone was running away and everyone, like myself, was screaming from being gassed in a frenzy. By the time everyone was dispersed, I lost contact with the group I marched with.”

“There were definitely deaths and bad injuries from open fire,” they said. “Even us protesters were taking care and checking on civilians who were at the scene.”

One confirmed death from Sunday’s riots was construction worker Eric Saber, a bystander who was reportedly hit by a stray bullet. Videos taken by eyewitnesses, as well as ABS-CBN News and Philstar, show police officers carrying guns and crowds being dispersed with tear gas and water cannons.

“It’s entirely possible na nauna [ang violence] sa mga protesters,” says Jenna Rodriguez, a public information officer for Samahan ng Nagtataguyod ng Agham at Teknolohiya Para sa Sambayanan (Agham). “Pero walang kalaban-laban ‘yong kanilang mga bato at bote sa mga baril, shield, at riot gear ng mga police. Hindi talaga makukumpara ‘yong response ng police doon sa mga nangyari. Kumbaga, sinobrahan.”

“Naniniwala kami [sa Agham] na regardless of kung kasama sila sa mga nagprotest — ‘yong iba nga bystanders lang — sa state at sa police talaga nagmumula ang matinding violence at human rights violations laban sa mga nagpapahayag ng kanilang opinyon against corruption…‘Yong sa mga nangungurakot ng pera ng bayan, mayroon na bang nakulong?”

Warrantless Arrests and Grave Conditions

Since the protests, more than 216 individuals have been arrested and detained across Manila’s police stations, among them 91 minors. Throughout the past week, several groups have taken to the MPD headquarters seeking immediate release for the detainees and justice for victims of police brutality, but the calls have only fallen on deaf ears.

During an indignation rally organized by women’s rights group Gabriela on Monday, September 22, police officers played Christmas music to drown out the protesters’ calls. “Buti na lang mas malakas ng kaunti ‘yong speakers na ginamit namin para sa program, tapos eventually, tinigil din nila,” says Rodriguez, who joined the rally with other members of Agham.

Families of the detained have also appeared at the gates of the MPD facility, imploring authorities to let them visit their children.

Human rights lawyers and those with the National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL) have been conducting visits to the MPD facility and other police stations, standing as the detainees’ legal counsel. In a statement, the NUPL pointed out that “physical abuse and torture [by police] were widespread and systematic,” and that the children were found with bruises. Among other findings were that “several detainees were forced to physically assault or restrain each other” at the police tent in Mendiola and the MPD facility, and that families were “pressured by police to coerce their children to admit to crimes they did not commit.”

Attorney Maria Sol Taule, deputy secretary general of human rights alliance Karapatan, tells Rolling Stone Philippines that authorities have allegedly been uncooperative with families and lawyers, who have flagged the arrests as illegal, especially as the inquest proceedings were held over 36 hours after the arrests, on September 23 and 24.

“Kapag warrantless arrest, may period tayong sinusundan para makasuhan sila, counted from the time of the arrest — not detention, ah. 12 hours kapag mababa ‘yong kaso, that includes some of the charges kagaya ng resisting arrest, malicious mischief o paninira ng property.” Taule said that these were charges faced by most of the detainees. A person arrested without a warrant must be presented to an inquest prosecutor within 36 hours at most, after which a judge decides whether the detention is justified.

Taule added that the police took long to file affidavits before the inquest because they could not determine all the detainees’ participation in the riots.

Charges were dismissed for detainees whose inquests happened on September 24, as they had already been in detention for over 36 hours. Many, however, remain in the detention facilities to suffer “grave conditions,” Taule said.

In her first visit on September 22, Taule said she observed that the detainees barely had the space in their cells to lie and sleep, that several of them were injured, and that they were reportedly not being given food and water.

“Nakatanggap naman kami ng reports na ‘yong mga Jollibee na pinapapasok namin, kinakagatan daw. Kinakagatan ng mga kung sinuman ang nasa loob, e mga pulis lang naman ‘yong nasa loob. ‘Yon ‘yong nirereklamo ng mga bata,” she stated.

In another instance, a person with disability (PWD) arrested during the protests told his mother that some detainees were forced to clean toilets. The child, who suffers from a mental disorder, was also reportedly beaten in the detention facility. “Ito ‘yong mga grabeng conditions na hindi natin nakikita ‘pag umaalis na ‘yong mga lawyers at mga relatives na bumibisita. Kaya grabe ‘yong takot namin at ng mga magulang, lalo na sa mga ginagawa sa mga bata ‘pag sila-sila na lang.”

When asked what could be done to hold authorities liable, Taule pointed to the Anti-Torture Act, which was established to ensure that no person under investigation or custody by authority shall be subjected to “physical, psychological or mental harm, force, violence, threat or intimidation, or any act that impairs his/her free will, or in any manner demeans or degrades human dignity.”

“May unnecessary na paggamit ng dahas while apprehending these individuals,” she said. “91 minors, including a nine-year-old. Napaka-questionable ng pagdampot ng police forces dito kasi ‘pag nakita mo sila, you can distinguish them from adults.”

Despite the alleged circumstances that the detainees face in detention, lawyers are hopeful that the charges against them will be dropped and that all will be released. For Taule, a necessary first step for the freed minors is to receive psychological counseling. “Ang gusto ko talaga, ma-ensure muna ‘yong welfare ng mga children. Nafe-feel ko ‘yong trauma nila. Sila mismo, dadalhin ito hanggang pagkalaki nila, ‘yong ganitong torture.”

“And then if the parents and the children are willing to file charges, kasi kailangang may magreklamo, we are very much willing to assist them sa korte,” she said. “Kailangang may managot dito. Hindi pwedeng nagpaputok ka lang, o kaya may nadampot na inosente tapos nagtatago ka lang dahil may kapangyarihan ka at poprotektahan ka ng gobyerno, tapos tapos na. Hindi pwede ‘yon.”