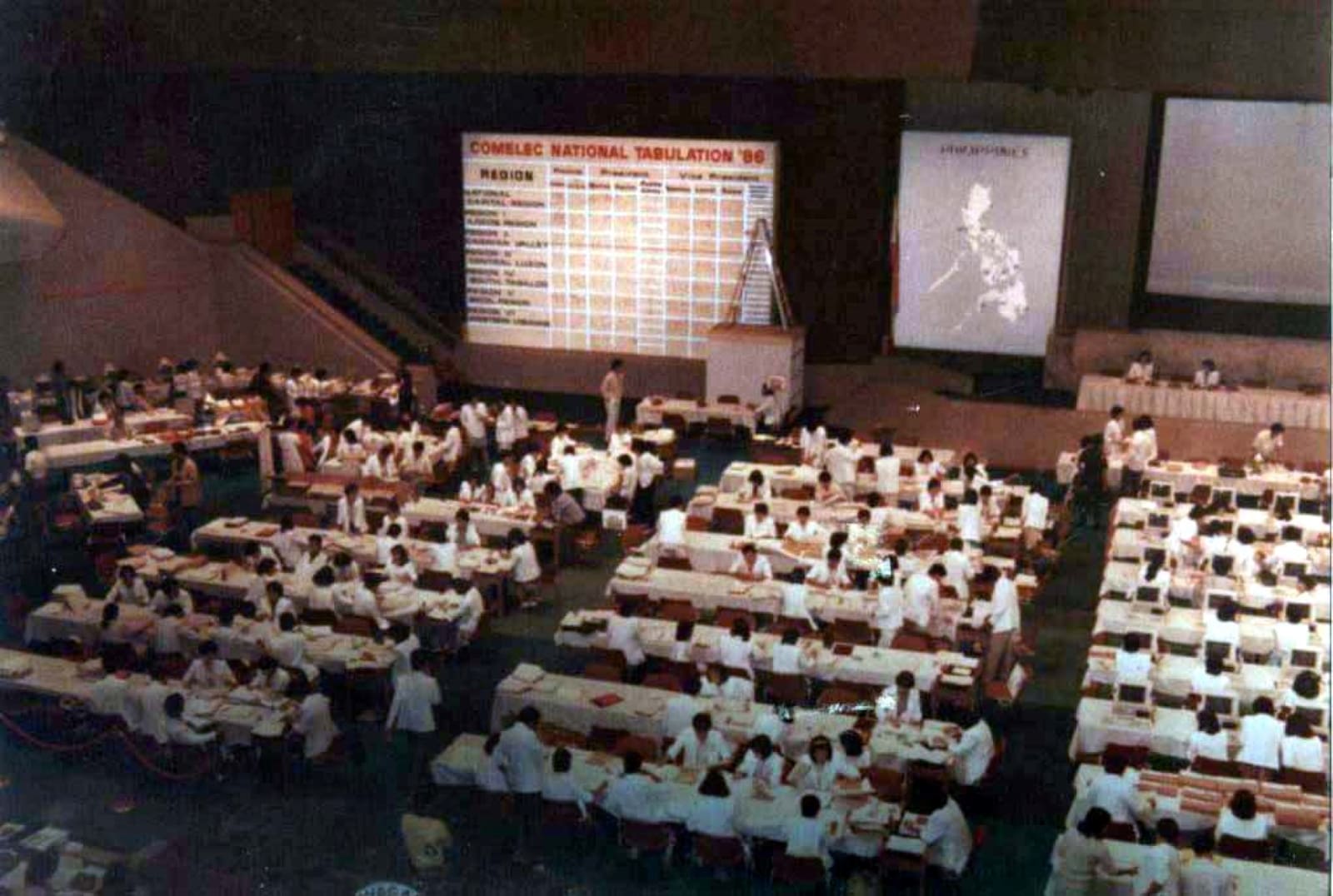

The 1986 presidential snap elections were held on February 7, but it wasn’t until the 8th that employees of the National Computer Center (NCC) began to notice the discrepancies between their own tabulation reports and the giant tally board in the Philippine International Convention Center’s (PICC) gallery.

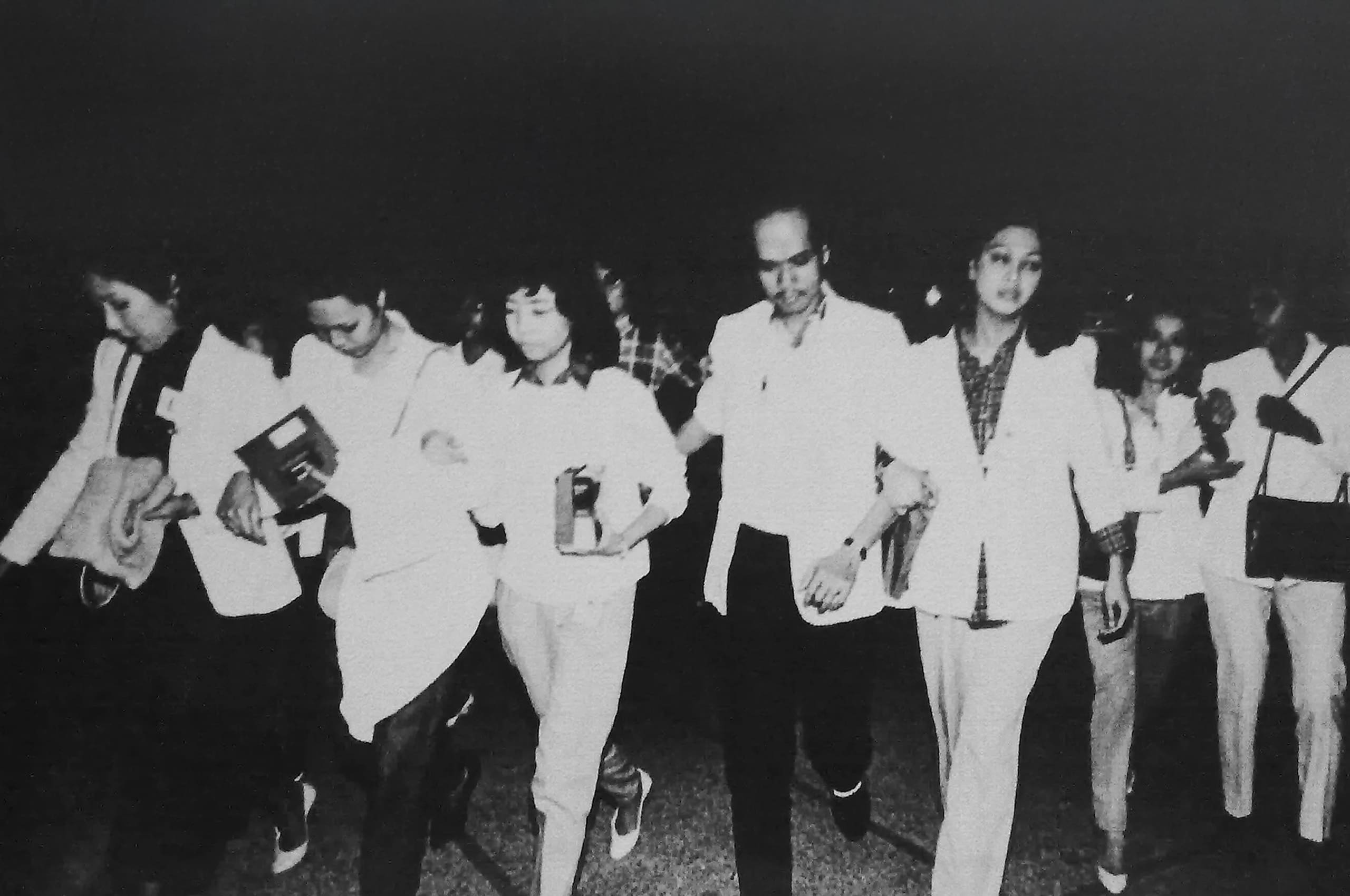

Then, on the evening of February 9, 35 of those employees — 30 women and five men — walked out of the PICC and into the crowded streets. Between the ruckus that ensued immediately afterward and the EDSA People Power Revolution that changed the nation two weeks later, the intent of the historic walkout was lost: the employees just wanted to go out for a drink.

They’re now known as the “Comelec 35,” even though they weren’t employees of the Commission on Election. Rather, they were employees of the NCC, a government agency that was established in 1971 and abolished in 2011, its functions transferred to the Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT).

Three members of the group recounted the walkout to Rolling Stone Philippines with a huge asterisk. “I cannot say I knew everything,” said Myrna “Shiony” Binamira, who at the time was a senior project manager in the NCC and oversaw the data entry activities. “What I’m saying now is from my own memory, my own perspective.”

A Foolproof System

On November 4, 1985, former President Ferdinand Marcos appeared on the ABC program This Week With David Brinkley, where he announced that he would hold snap elections to prove that the Filipino people were satisfied with his leadership. A month later, the Batasang Pambansa passed a law setting the election date to February 7, 1986 — only a year before the regular national elections were supposed to be held.

According to Binamira, the government first looked to the private sector to process the elections before the project was given to the NCC in January 1986 to cut costs. The existing NCC employees had to learn the system, recruit data entry operators, and then teach them the system in the few weeks they had before the elections. “These people practically lived in NCC that one week before the election,” she said.

“And the added complexity pa is we had to make it right,” she added. “We wanted the program [to be] something that cannot be cheated — the security and controls and everything. The system designers and analysts were very, very particular about that.”

Dennie Vista, then in charge of quality control, said that the controls were placed even at the precinct level. “For example, [if] a precinct has 100 registered voters, only 100 votes can come from that precinct. That’s how stiff the validation and controls that we placed [were],” she said.

Binamira also said that during the tallying, the system flagged repeating precinct numbers and other sorts of errors, stretching out what was only supposed to be a 24-hour count. “We left on the ninth, which was already two days [since the elections], and we were still not 50 percent [through],” she said.

Ironically, the red flags were supposed to be a sign that the vote-counting system was working. It meant that the elections could not be cheated. The NCC employees were sure — “excited,” even — that nothing in the elections would go awry because they did their job. In the days leading up to the walkout, they were determined to make history by keeping the elections clean.

Some of us left the country, some of us continued hiding. And then some of us went to EDSA.

But on February 8, when the staff observed that the results on the tally board weren’t matching up with the tabulation reports, Binamira told another staffer to check the programs for bugs. “It’s possible na magka-bug kasi. Sabi ko sa ‘yo, one week lang [ang preparation] e,” she told Rolling Stone Philippines. “But [the programmers] were so absolutely, confidently sure: ‘Wala itong bug, Shiony.’”

Achie Jimenez, a programmer in charge of tabulating the votes from Regions IV and V, said that the NCC did not even have a program complex enough to be bugged. Their task was simple: add the votes.

She explained that after receiving the results from the precincts via telegram, data entry operators only had to plug the results into diskettes, which were then given to another staffer in charge of tabulating the national tally and printing out the reports.

Vista, who was tasked with crosschecking these reports, further explained that she first had to sign them before handing them to Comelec. The commissioners took the papers to the “small office at the back” before officers came out to write the numbers on the board by region.

The tally was also published late. “Eventually, they posted, but it was not the same as the report I had,” Vista said. “The numbers were less than what we actually counted.”

“There were 13 or 14 guys who would climb these steps to post [on the board], and they all had one small paper each,” Binamira noted. “Sabi ko, ‘Saan kaya nangyayari ‘yong change?’”

Lapses in Transparency

The gallery was open to the media and citizens when the elections started, but by the morning of February 9, no one was allowed to walk in and observe the tallying anymore, Binamira said. The gallery was empty, but the note posted on the door said, “The gallery is full.”

Former United States Senator Richard Lugar, then chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, had flown to the Philippines to monitor the elections. He visited the PICC the same morning, and only then did the numbers on the tally board reflect the NCC’s reports, Vista said.

“When that happened, we were kind of, ‘Ah, okay. So there’s no bug!’” she said. Lugar’s delegation also validated the reports and were “impressed” by the NCC employees.

“When Lugar and party left, hindi na naman pareho,” Binamira said. Vista noticed that some of the regional numbers posted in the afternoon update were more than what the NCC had counted. To them, it was confirmation that something was amiss.

“E kung ganyan din, mag-walkout na lang tayo,” Jimenez heard someone say. It wasn’t even a cry of protest or defiance, she said, but an expression of frustration. The numbers on the tally board proved futile the programmers’ efforts to keep the elections fair and transparent.

A few employees gathered in a room, where Binamira asked them what they wanted to do. “And all of them unanimously said, ‘Uwi na tayo,’” she said.

After dinner — the only time that they could all gather — the employees agreed: “Mag-inuman na lang tayo.”

Linda Angeles-Hill, another senior project manager, had called three cars, expecting only 10 or 15 people to walk out that night. Instead, 35 of them stepped out of the PICC to find crowds of people, concerned and angry, telling them that they could get killed. “That was the first time we realized…that we felt fear. Some of the girls were crying na. And the people, they formed a human chain around us and they were shouting, ‘Let’s protect them!’” said Vista.

Amid the chaos of the mob and growing fears that there would be consequences to the walkout, they squeezed themselves into the three cars and sought refuge in the National Shrine of Our Mother of Perpetual Help, or Baclaran Church. But even there, they were not spared from the crowds and the media.

The church was packed and its windows were boarded up with plywood (“Kasi daw ho baka may mga snipers,” they were told) when the group gave its statement at the altar, their backs to the pews. There, the Comelec 35 gave their only public statement, which they wrote in haste and read to the media:

“We were made to believe from the start that the job was going to be a professional one. The honor, responsibility and challenge that we saw in the project were enough to vindicate the hard work and long nights spent developing the computerized system before it was to start operating on February 7, 1986.

We emphasize that it was a spontaneous act of protest; we have no leader, we are not syndicated, nor do we wish to be linked to any partisan motives. None of us has any political affiliation. We are just independent-minded persons whose only desire is to preserve the purity of our profession.”

They also clarified that they were not ordered to cheat the results, nor were they trying to “sabotage the system.”

When the group was done reading the statement, the church was cleared out and the NCC workers made their way to Angeles-Hill’s house in Camp Aguinaldo, which was like feeding oneself to the monster, Binamira said. An emissary of late Manila Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin later on got in touch with them and told them to go to the Loyola House of Studies in Ateneo de Manila University. “Pinalagyan ng numbers ang shoes [namin]. Ang sabi kasi, if somebody turns up dead and you find the shoes, at least you can identify who it is. ‘Di ba nakakatakot?” Jimenez said.

Some of the girls were crying na. And the people, they formed a human chain around us and they were shouting, ‘Let’s protect them!’

They only stayed on campus for a few hours, drawing up another escape plan. Cardinal Sin wanted to split the group to make them harder to hunt down, but Binamira insisted that they all stay together so she could keep an eye on all of them. So they decided to go to the Cenacle Retreat House, only a short ride away from campus. The convoy, led by a decoy of seminarians wearing cloths over their heads, felt like hours partly because of the tension and partly in an effort to mislead those who might be following them. Not even their families were told where they were.

The vigilance was not unwarranted. “We were getting messages from our families [saying] that they’ve seen suspicious people roaming our houses,” Binamira said. So they stayed in the retreat house for ten days, in the care of nuns and members of the Reform the Armed Forces Movement (RAM), including Lieutenant Colonel Eduardo “Red” Kapunan, then the husband of Angeles-Hill before their split.

The Aftermath

On February 15, the Batasang Pambansa declared Marcos the winner of the snap elections, but the results were contested by the National Citizens’ Movement for Free Elections (NAMFREL), who said that Corazon Aquino won the elections. By then, the walkout and a statement by Cebu Archbishop Cardinal Ricardo Vidal had stoked suspicion among the people that the elections were cheated.

On February 20, RAM told the walkouters it was safe to go home. “Some of us left the country, some of us continued hiding,” said Jimenez. “And then some of us went to EDSA.”

Banking on the increasing political instability at the time, former Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile and former Philippine Constabulary Fidel V. Ramos staged a coup d’etat on February 22. The coup failed, but at Cardinal Sin’s urging on Radyo Veritas, people gathered at EDSA to show support for the rebel leaders, starting the People Power Revolution.

On February 25, Aquino and Marcos were both inaugurated president, but Marcos fled the following day, effectively removed from power. His departure marked the end of the revolution and his 20-year dictatorship.

The Comelec 35 gather every February 9 to celebrate the walkout anniversary. In their gatherings, they still try to piece together the events and details of the walkout. “‘Yong mga kwento [ng iba] up to today, first time I’ve heard it,” said Binamira.

“We were all in different roles in PICC, so we only knew what we were doing on our own,” she explained. “That’s why we keep seeing each other, because then we learn something new every day.”