If it were only up to Lav Diaz, his latest historical opus, the 16th-century pictorial fresco Magellan, which just premiered at the 78th Cannes Film Festival, would run for 40 hours and most likely be shot in monochrome. “To let it just grow and grow,” he says, thirty minutes deep into our conversation alongside actor Hazel Orencio (who plays Reyna Juana in the film), a week before heading to Cannes. “Kulang pa sa akin e.”

Seven years ago, when the Filipino auteur began researching about Ferdinand Magellan and his colonial expedition across the Malayan archipelago, he was convinced that his labor would culminate in an onscreen saga that moves past a mythical portrayal of the Portuguese navigator, played by Mexican star Gael García Bernal in the movie. This is a historical saga by way of Lav Diaz. He cuts no corners, in style as in thought. But a 40-hour retelling of Magellan is admittedly a moonshot, considering what his pockets could afford.

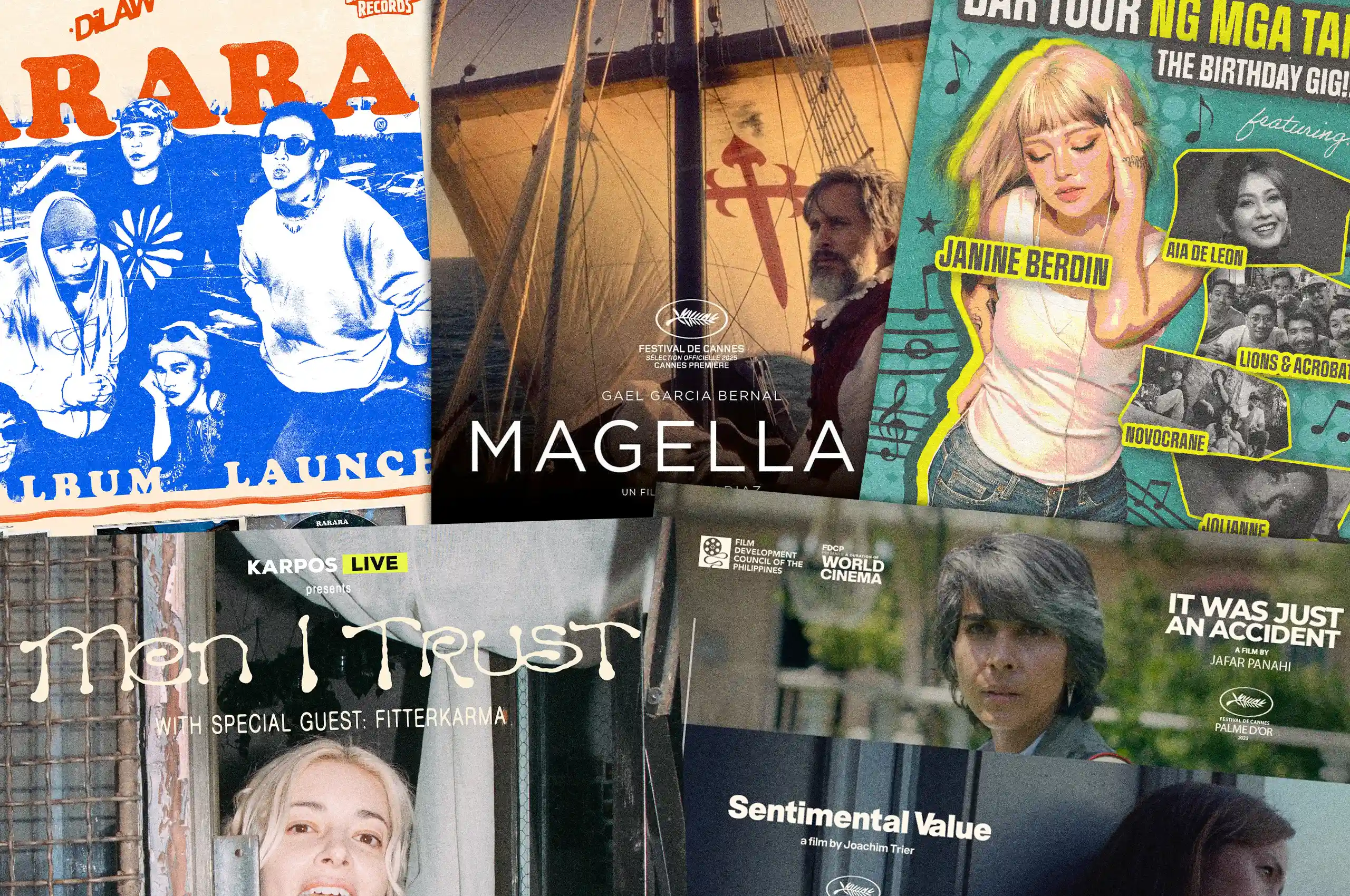

For now, Diaz settles for a 156-minute, “acid trip” version of the Cannes Premiere title. But he still intends to release a nine-hour, novelistic cut of the movie, which was shot in color across the Philippines and Europe. Magellan marks Diaz’s return to Cannes, after premiering the Dostoyevskian drama Norte, Hangganan ng Kasaysayan in Un Certain Regard in 2013, and the dystopian epic Ang Hupa in Directors’ Fortnight in 2019, the same year he announced the Magellan project under the working title Beatriz, The Wife.

Since the late 1990s, Diaz has been one of the most prolific arthouse filmmakers, producing films nearly every year to great international renown. Over imposing hours of footage, he takes on the mantle of curious historians, fixating on boundless questions of how and why, from the most granular to gargantuan, that fracture the lives of the common Filipino and humanity at large.

His characters are tortured by a past they cannot seem to outrun, and the moral reckoning often manifests in the form of physical maladies, especially in Diaz’s recent titles Kapag Wala Nang Mga Alon (2022), Essential Truths of the Lake (2023), and Phantosmia (2024). Even his upcoming political drama, Kawalan, set in Japanese occupation-era Philippines and shot two years ago, centers on characters succumbing to tuberculosis, the diagnosis Diaz himself received after wrapping up production for Magellan. While Magellan’s titular character isn’t hounded by a recurring bodily malaise, the movie nevertheless sustains Diaz’s harsh assertions on human frailty, mythmaking, and colonial violence.

In this two-hour interview, which has been condensed and edited for brevity and clarity, Diaz and Orencio detail the making of the movie, their collaboration with Bernal, the arthouse director’s close brush with death, and why cinema still feels limiting to Diaz.

I learned that instead of Magellan, the story was supposed to be anchored on his wife, Maria Caldera Beatriz Barbosa. How did the story evolve from that?

Lav Diaz: Well, it started with Beatriz talaga kasi we’re trying to find a story na hindi na gasgas. When we decided to work together in Spain, Portugal, and the Philippines, ‘yong initial readings ko, I realized na ang liit lang ng naisusulat about Beatriz. Most are three lines, four lines. The wife of Magellan, the daughter of Diogo Barbosa (one of the best friends of Magellan), and the sister of Duarte Barbosa (the son of Diogo Barbosa, another best friend of Magellan). ‘Yon lang ang nasusulat. She had two sons with Magellan tapos namatay pareho in 1521, Magellan and Beatriz. Doon nag-umpisa ‘yong kuwento.

I worked on Beatriz. Ang impetus noon kasi ay may kalayaan akong gumawa ng kuwento kasi wala namang kuwento sa kanya, e. Talagang obscure siya na character. So, I wrote a story around her. Dahan-dahan lang, the last seven years while reading and reading and reading.

Then ultimately lumaki na rin ‘yong kuwento ni Magellan kasi may mga na-realize akong mga hindi pa naisusulat. Sa investigation ko, parang hindi totoo si Lapulapu. Parang inimbento lang siya ni Rajah Humabon. If you investigate it well, ang pinaka-comprehensive na writing lang about it was [Antonio] Pigafetta’s. And there’s another one by Miguel [de] Mafra, kaya lang it was lost. So, ang reference mo lang talaga is Pigafetta and then the accounts of the survivors na conflicting. Pero iisa lang ang narrative. Magellan died on April 27, 1521, and then May [1, 1521], the Cebu massacre happened. Very clear ‘yon. Pero ‘yong case ni Lapulapu is not clear. ‘Yong case ni Beatriz, ang labo talaga. So, doon ako naglaro.

And if I’m not mistaken, Lav, Magellan is by far your furthest foray into Philippine colonial history. Parang timeline-wise, if I remember your past work. And I’m sure there’s a whole lot of research involved. Can you speak more on the research and the liberties you took while working on the film?

Diaz: Well, I took liberties on the dominant view na they discovered the Philippines. They didn’t discover the Philippines naman. In 1506, they were already in Malacca. Ang lapit na sa atin noon. The first expedition, they went to Malacca. Magellan and his best friend, Francisco Serrano, knew already of islands in the northwest of Malaysia na ang tawag nila “Islands of Gold” kasi may mga Luzones, may mga Bisaya na nakakarating sa Malacca. Malacca is a big market. Maraming villages sa Malacca na mga Malays ‘yong nag-ma-market. So, I took liberties on that trading story around Malacca. Doon ko na rin hinugot ‘yong idea na maaaring doon nagmula si Enrique. He became a big character in the film [as] the slave of Magellan. He was bought by Magellan in 1511, the second expedition nila sa Malacca. He brought him to Spain. He became the interpreter pagbalik nila sa Southeast Asia. Binalanse ko ‘yong kuwento. May Malay perspective siya. There’s the voice of the Malay now. Hindi lang siya perspective ng West.

Were there any places you had to visit as part of your research?

Diaz: Nag-stay kami doon sa Seville, where it all happened, ‘yong preparations for the expedition. Pinuntahan namin ang mga places sa Portugal kung saan umikot-ikot sila Magellan. Sa third na pagpunta ko sa Lisbon for research, sinama ko na si Hazel doon. And then we went to Seville. We checked the places na na-inhabit nila noon. And in Seville and Portugal, andoon pa ‘yon lahat e. Untouched. They preserved the places well para madali sa shooting.

I want to go back to your point earlier na footnote nga lang si Beatriz Barbosa sa story ni Magellan. How important was she to the vision that you had?

Diaz: Ang idea ko kasi kay Beatriz noon, I want to create a really good story around the Magellan saga, hindi lang itong expeditionist or journeyman who wanted riches and power kasi hindi [niya] magawa sa Europe. I think there’s a good story around their love story. And one thing na gusto kong i-connect talaga, a big conceit, kung saan nanggaling si Santo Niño. Santo Niño is a big, big factor lalo sa conversion ng mga Cebuanos, ng mga pintados, so I connected that with their love story.

Now, I want to talk about Gael García Bernal, your Magellan. What was it like working with him for the first time, and how did he first get involved with the project?

Diaz: He was recommended noong naghahanap kami ng actor. And then all of us, we think he can be Magellan kasi hindi siya masyadong malaki at very Portuguese ‘yong features niya. When he said yes, he met up with [producers] Albert Serra and Joaquim Sapinho in Berlin. They had a drink, and he said, “Okay, I want to meet Lav.” And then pumunta kami ng Lisbon, pumunta siya ng Lisbon. We ate, we drank. Nagkwentuhan kami. I think he’s okay. Of course, iba na siya ‘pag shooting. Mga actors, ganun e. Suddenly iba na sa shooting. Ibang setup na.

It’s just like music, you keep going, you keep playing the guitar. For me, it’s a language that I keep inventing and reinventing and understanding. Hanggang ngayon, I couldn’t understand cinema. It’s just a medium. I’m just a storyteller.

Has he seen any of your films prior to production?

Diaz: Pinag-aralan din niya. Alam niya ‘yong process e. And he’s from Mexico City, and the most popular festival there was the Ficunam. And in Ficunam, regular din ‘yong films natin doon. Lagi rin siyang guest doon. I think he’s awesome in the film. And he’s the usual actor. Ang kaibahan lang, very Hollywood ‘yong perspective niya. I would say para siyang Hollywood ideology, the big setup. So there’s the adjustment with the process, with the setup, with how you look at things kasi Southeast Asian ang perspective natin, sila American and European.

Was there anything that you compromised with Gael in terms of how you wanted him to portray the titular character?

Diaz: Nakikinig naman siya. But then gagawin niya ang gusto niya. Ganoong klase. Pero kailangan sabihin mo rin ang gusto mo, “I want you to move, to do this, do that.” Kami lang dalawa ang nagkukwentuhan about these things. May mga ayaw siya, i-a-adjust ko siyempre. [I’ll tell him], “If you don’t want to do that, okay.” May mga i-sa-suggest siya na okay naman, [I’ll tell him], “Okay, do it.” Ganoon lang. It’s all adjustments. Medyo psychiatric lagi ‘yong approach, e. You psychoanalyze everything and work around those.

Ganoon lagi with Gael, kasi napakaintelihente niya. Mysterious siya, hindi mo nakukuha masyado. But then it’s nice and it’s telling us things in the process. Mas natututo rin ako to work around people [who are] like that na iba rin ‘yong process nila. May iba silang perspective. Gael grew up with theater. From a theater family siya sa Mexico. They have this thing about acting, so adjust ka rin doon. Of course, ‘pag director ka naman, obserbahan mo lang sila, makinig ka lang, makinig sila sa iyo, it’s easy na. Ang mas nahihirapan ‘yong mga tao sa paligid. Hindi ako.

Speaking of mga tao sa paligid, how about you, Hazel? How does it feel to have Gael as your co-actor? Did you have scenes together, and then paano siya sa set?

Hazel Orencio: Well, in terms of eksena, wala naman akong problema. Kaya ko naman makipagsabayan. And not just me, but also the other Filipino actors like Ronnie Lazaro. It’s fun watching Ronnie Lazaro with Gael. Nakaka-proud. Talagang kaya naming makipagsabayan sa kanya.

Diaz: One thing I noticed noong eksena nila, talagang it was the first time na umiyak siya nang husto.

Orencio: Oo, totoo.

Diaz: So ‘yong epekto ninyo noong apat kayo, pati ‘yong batang maysakit, it was very powerful kasi nag-flow siya doon. Dahil sa ginawa mo at ni Ronnie.

Orencio: Kasi mag-asawa kami ni Ronnie.

Diaz: When he came in sa scene, talagang nawala na siya. He was just weeping. Sabi niya, “Wow, it was very powerful.”

Orencio: But minsan mas meaty ang behind-the-scenes story. Actually, marami ‘yan. Si Lav kasi kaya niya e, because he’s always [acting as] the psychiatrist sa shoot. He can work around sa mga toyo naming lahat and not just the cast, the crew, lahat.

Diaz: Ang daming kaguluhang nangyayari, pero okay lang.

Orencio: Even with Gael, he can work around it. Pero kasi ako as the production manager, masakit talaga ulo ko. Lalo kasi it’s a major adjustment for us dahil you know us, Lé. Talagang lean kami e. We’ve always shot in lean numbers. Talagang marami na sa amin ang bente. We were like family. And suddenly we had to be 150. Bilangin mo pa ‘yong extras, nasa 200 kami.

Imagine mo ang dami-daming pinapakain. And that’s different cultures, different sa pagkain. Not all of them gusto ‘yong Filipino food. Not all of them are into meat. Alam mo ‘yon. Sobrang daming adjustments. We had to combine ‘yong Sine Olivia [Pilipinas, Lav’s production studio] production pati ‘yong production ni Paul Soriano [Black Cap Pictures] kasi kailangan na namin ng backup.

Diaz: When we shot in Europe, tatlo lang kaming Pilipino. Siya, ako, at si Arjay. Iba rin ‘yong process nila. Para silang machine. Everything was set up. Nandoon lahat.

Orencio: Although hindi sila ganoon kadami. ‘Yong problem was flying them here, so Philippine shoot talaga ‘yong andami namin talaga. Imagine mo, iba-ibang temperament. Buti naitawid.

Diaz: Natapos naman. I wish tumagal pa nga nang kaunti parang may mga gusto pa akong idagdag e.

Orencio: They have to follow a schedule. Sobrang strict nila with the scheduling.

Diaz: Sanay kami na open ‘yong schedule.

Orencio: Doon siya nakaka-flow as a writer. Ganoon kami, inaabangan namin what will happen the next day. Ito, hindi, you have to have the script in advance.

Diaz: I broke my process here.

Unlike before na you can write and edit in the set.

Orencio: Nakaka-edit pa rin. Nakakalusot pa rin siya minsan, kaya lang si Gael kasi hindi siya ganoon ka-flexible when having additional lines.

Diaz: Spanish-speaking siya, so we had to translate it to Portuguese. Kaya ayaw niya na bago ‘yong script. At least five or seven days in advance para mapag-aralan niya ‘yong Portuguese part of the script, ‘yong pagsasalita, tone. Although kayang-kaya niya, pero kailangan niya ng preparation.

As usual, you gathered your frequent collaborators here: Hazel, Amado Arjay Babon, Ronnie, Bong Cabrera, and so many others. What was it like working constantly with these actors? Do you still have to instruct them, or tell them how to approach their characters, or is everything more instinctive and fluid now?

Diaz: Very fluid na talaga. I give them the script and then okay na sila. Sila na lang nagtatanong sa akin, “Ano gusto mo dito?”

Si Hazel, ayaw niya kasi na pinagsasabihan e. [Hazel laughs] Si Ronnie, we talk about Jesus kasi Jesus freak siya ngayon. We talk about rock and roll. Si Arjay naman, we talk about Karl Marx.

Orencio: Si Bong, it’s his first Lav Diaz [film], and also Sasa Cabalquinto, the one who played Babaylan. Pero okay sila, lalo si Bong kasi nga perfect siya talaga as Kulambo. Aside from he speaks Bisaya, ‘yong height din niya. And talagang ang ganda nila tingnan ni Ronnie. In sync talaga sila.

Diaz: Kahit si Gael and Arjay, ang ganda.

Orencio: Para kang nanonood ng stage play whenever may eksena. Si Arjay, very perfect siya, and he worked hard for the role kasi talagang nag-aral siya ng Portuguese. So imagine he’s speaking Bisaya with Ronnie, and then he has to translate to Magellan in Portuguese.

Diaz: In the case of Gael, ‘pag may kaunting pagkakamali lang siya sa tone ng [pag-ko-code] switch from Spanish to Portuguese, after that cut, kakausapin ka niya kung pwede pa bang isa. Metikuloso siya. Real actor talaga. Hindi ‘yong “Okay na ‘yan.” Hangga’t hindi niya nakukuha, gagawin niya.

Hazel, what can you tell us about your character, Juana? And how does it feel to be an actor in the film, but at the same time a production manager? How do you balance that?

Orencio: ‘Pag pinapaarte ako ni Lav, it feels like nagpapahinga ako kasi, first and foremost, actress talaga ako, e. So nevermind all the gulo as a production supervisor. The moment na I’m in costume, nasa character na ako. Especially for this film kasi I had to learn Bisaya, so nakaka-pressure, tapos sila Ronnie, sila Bong, ang gagaling nila.

At some point sabi ko, “Hala, hindi na ako nakaka-prepare as Juana.” Pero naitawid ko naman, even ‘yong pag-Bisaya. Grateful ako kay Lav, kina kuya Bong na inaalalayan ako. And of course, ‘yong AD namin si Sanny [Joaquin] because she’s Cebuana, so inaalalayan nila ako with my speech.

Diaz: ‘Yong character mo ay ‘yong reason [why] the Santo Niño became the biggest icon in the Philippines.

Orencio: Gusto ko ‘yong scene na ‘yon, where I was screaming. Hawak ko ‘yong Santo Niño, and I was telling the villagers na, “Heto si Santo Niño, totoo siya.”

Diaz: Grabe ‘yong conversion [to Christianity] because of that. That was described by Pigafetta. We tried to reenact it. Ang daming hubaran doon, ‘yong mga pintados doon, hubad talaga ‘yong mga Malay people, except for Rajah Humabon and the wife.

Orencio: Hindi kami ‘yong usual na period [film] na may mga tapis pa. For this one, talagang we hired actors who are willing to strip, so talagang naka-tattoo lang sila, talagang naked sila. Hindi ko alam kung mapapalabas tayo dito because of that.

Given the scope of the film and ‘yon nga being naked, was there any intimacy coordinator present on set or at least similar to that?

Orencio: Wala kaming ganoon.

Even sa theater kasi ‘di ba pina-practice siya. So, how did you handle that given na malaki ‘yong cast?

Diaz: Well, mahaba ‘yong period ng casting. We had six months to prepare. Naghanap kami ng mga tao talaga. The casting group, with Hazel on the group, naghanap sila ng papayag. We explained the whole thing. It’s about 15th and 16th century, and Malay tayo, and during the period, hubad talaga ang mga Malay, pero ‘yong mga royals lang medyo nagdadamit, so kailangang maging truthful tayo sa panahon. Ipakita nang totoo na wala tayong saplot. And a month before the shoot, nakumpleto naman namin lahat.

Orencio: We were shooting in Europe ng October to November. Nakapag-start na kami dito ng September, but we decided na mas maganda mag-start sa Europe. But casting was happening.

Diaz: June pa lang, nandito na sila. We have to assure people, ‘yong mga umoo, na they’re safe. But you know, kailangan ipakita lahat. Walang tinatago. They’ll be safe, walang mababastos o mamomolestiya.

Orencio: Nakakuha naman kami, luckily. ‘Yong iba ay performance artists who are very game to doing this na wala talagang keme. ‘Yong iba naman ‘yong mga professional talents who are used na sa TV and very game sila and talagang ang laking bahagi rin nila sa film.

Diaz: Naunawaan naman nila kung ano ‘yong gagawin nila. Ano ‘yong kuwento. Ano ‘yong panahon. Sa kanila, it’s okay. Awareness at understanding lang ‘yon e. Kailangang ipaunawa mo na hindi siya porn.

Orencio: ‘Yon din ang isa sa mga naging mahirap i-handle because we always had to make sure before shooting, lalo if involved itong mga pintados, mga nude artists, we always have to make sure na ‘yong set walang ibang tao. We always have to make sure na protected sila. So imagine there’s 30 of them, so talagang naka-standby ‘yong mga wardrobe at assistants namin. Every cut, siyempre tatakpan namin sila ng malong para hindi sila mabastos.

Did the filming process happen like a back-and-forth, or did you complete shooting all scenes in one location first before proceeding to another?

Diaz: ‘Yong Philippine part ang inuna pero it became problematic. May mga problems with communication, with the schedules. Medyo may culture clash pa nang todo, so we had to stop that and then nag-break kami ng one month, and then we started the shoot na sa Portugal. We stayed there for a month and then two weeks in Cadiz, Spain, and then back to the Philippines, dire-diretso na ‘yon.

Orencio: The total shooting days [was] 42. Pero kasi may shoots na kayo-kayo lang. Noong September, there were four shooting days, but only one with Gael. We resumed in Europe, in Portugal. ‘Yong Europe shoot was divided into three. Ginawa nilang per parts, parang episode din. So, the first part was ‘yong nagkakilala si Magellan at si Beatriz somewhere in Portugal. And then the second part was in Cadiz, Spain. This was ‘yong shinoot na namin ‘yong ship scenes. The European team had to rent a museum ship, Victoria.

Ito lang ‘yong nag-request sila na, “We want your work, but we want a limit.” May ganoon na sila. “Huwag ka lumampas ng tatlong oras.” So, nag-decide kami with the producers na, “Okay, gawa tayo ng para sa kanila, gawa tayo ng totoong version mo later.” Pero sabi ko, “No, totoong version ko pa rin ‘yan.”

One of the ships of Magellan.

Diaz: The Victoria, ni-renovate lang nila.

Orencio: Two weeks din kaming nasa barko. Pero of course everyday naman ‘yon dumadaong. Ang hirap kasi ang lamig-lamig and all. And then we went back to Portugal again. Supposedly, [the next location was] Seville, kaya lang I think there was a problem with the location or what, kaya we had to go back to Portugal na lang, sa Serpa.

In fairness naman sa kanila, the way Lav wrote the script, sinunod naman nila ‘yon. Kaya lang, there were scenes sa Cadiz which we weren’t able to shoot because of actors’ availability. Budget constraints din. Kasi they were thinking na the whole time we were in Cadiz, talagang nasa barko lang kami. Pero may scenes na we had to shoot sa shore. Kaya ‘yong mga scenes na ‘yon, dito na shinoot sa Pilipinas. That’s why dumami rin talaga kami dito kasi instead of [the] Cebu scenes na lang ang i-su-shoot dito sa Pilipinas, we ended up shooting the remnant scenes na dapat natapos na noong Cadiz pa lang.

And what was it like working with cinematographer Artur Tort [for Magellan]?

Diaz: Si Artur naman, alam na ‘yong mga pelikula ko, so ‘yong mga European scenes, siya halos ang kumuha. ‘Yong Philippine scenes, hati kami. May kasama siyang other French cinematographer, but they followed my language. Apat kami na nag-camera dito: Artur Tort, ako, and other Spanish cinematographers.

Lav, you already mentioned earlier that you had a plan for a nine-hour cut of the movie, but, of course, the version submitted to Cannes is only about three hours. Did you have a hand in editing the Cannes version, or was it totally the decision of the producers?

Diaz: Ni-rough cut. Ang cut ko three hours tapos napaiksian pa nila.

And how did you wrestle with that kind of adjustment, considering the artistic control that you have?

Diaz: Mahirap talaga pero kailangan mong tanggapin din ‘yon. The shorter version is another film. It’s not a short film. ‘Yong nine-hour film later, or maybe ten hours, it’s another film.

Orencio: But at the same time, wala rin kaming magawa because right after finishing the three-hour cut, this was in January, nagkasakit na siya. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis.

Diaz: Sumuka ako ng dugo.

Orencio: So, the whole time they were editing, naka-focus naman kami dito sa kanya because he was sick.

Diaz: When I did the cut, naipadala na namin. Tapos sumuka na ako [ng dugo].

Orencio: Hindi niya sinasabi sa amin na four days na pala siyang sumusuka ng dugo. So, by the fourth day, he was showing me his hand, [tapos sabi niya], “Hazel, dalhin mo na ako sa hospital.” Noong dinala ko siya sa hospital, wala na. Tuliro na ako. Pero okay na siya. He’s under medication.

Diaz: The first time I vomited, river of blood talaga. Naliligo ako, it’s all blood, sa ilong, bunganga. ‘Yong first talaga, muntik na ako doon. I was [holding] the rails of the door sa banyo. Yeah, sometimes, you romanticize that. Ang sarap pala mamatay, no? With blood!

Orencio: No!

Maraming namamatay na artists recently, ‘wag naman sana agad, Lav.

Orencio: Ewan ko dito.

Diaz: It magnifies the whole journey na, “Okay, ganito pala ‘to.” I’ve seen death. Hindi naman pala nakakatakot ‘pag nandoon ka na. Magellan is about death. The only truth in that [film] is death.

At least he’s okay na. And back to your point earlier about the condensed cut submitted to Cannes. Do you think it has to do with the current economy of international film festivals? Are they no longer friendly to films with longer duration? Kasi I noticed na parang mas umiikli ngayon ‘yong mga sina-submit mo sa international film festivals.

Diaz: Napansin ko ‘yan [in] the last five years. ‘Yong dating friendly na mga programmers sa world cinema turned their backs. Parang hindi na nila ako kinakausap. Kasi umakyat na rin sila sa positions nila. From simple programmers, nagkaka-position na sila. They forget about you. They don’t care about you anymore. But I don’t want to use that word na parang nagamit ka lang para sa resume nila. Supposedly responsible programmers, but now they don’t even consider my work. Wala na. ‘Pag nakita mo sila sa festivals, you just say, “Hi. Hello, how are you?” It’s cruel, ‘yong culture ng programming ng festivals. We have to work around these things just to show our cinema. For me, wala akong pakialam doon. I’ll just do my cinema.

Orencio: I think ito lang namang Magellan ‘yong kailangang may condensed version. But the rest naman, hindi naman sadya na pinaikli kasi other fans [were saying din], “Bakit umikli?”

Diaz: Ito lang ‘yong nag-request sila na, “We want your work, but we want a limit.” May ganoon na sila. “Huwag ka lumampas ng tatlong oras.” So, nag-decide kami with the producers na, “Okay, gawa tayo ng para sa kanila, gawa tayo ng totoong version mo later.” Pero sabi ko, “No, totoong version ko pa rin ‘yan.” It’s a different film. I treat these two things as different films. The Cannes film is the Cannes film. The ten-hour film later will be another film.

Most of your films display a profound sense of verisimilitude, o kung hindi naman ‘yon, may magical realism. Does Magellan possess both qualities? How does the film actually veer away from previous iterations of the Magellan saga? And would you say that this is some sort of rewriting of Magellan’s history?

Diaz: I’m very sure na I’ll be accused of revisionism. Kung sino si Lapulapu, the massacres that happened, and the way I invented the story behind Beatriz, the trajectory of the Santo Niño and how it became the biggest icon of the Philippines, and the conversion of the Filipinos. Yeah, I expect that.

But I want that. To create a greater discourse on the issue. Until now, kahit ang dami ng television series na nagawa kay Magellan, cinema, books. [When] you read the books, we keep revising the whole thing. May mga facts lang na nagkakatugma. May mga facts na hindi nagkakasundo-sundo. Ang history talaga, it’s a complicated thing.

I think the only thing that I can say is I did my homework with this job. I read a lot in the last seven years. I was reading and reading books about Magellan. You realize so many things na, until now, it’s all the same. We’re still barbaric, we’re still the same. Hindi nagbabago ang tao talaga, kahit na we’re advancing and advancing. But no, we’re actually retrogressing and retrogressing.

I’ve also noticed that throughout your career, you produce films almost every other year. I’d like to know what keeps you going and how you continue to come across stories that you think had to culminate in a film.

Diaz: It’s just like music, you keep going, you keep playing the guitar. For me, it’s a language that I keep inventing and reinventing and understanding. Hanggang ngayon, I couldn’t understand cinema. It’s just a medium. I’m just a storyteller. To say it’s cinema, sa akin very limiting ‘yong idea na it’s cinema. I cannot even compare cinema to the greatness of the novel form. Sa akin, ang dream ko sa pelikula is to create something that achieves that level of the novel or even the epic poem. There’s just too much adornment, artifice, lahat. And kulang na kulang pa. The only thing that matters now is, yeah, masasabi kong I’ve created my own language in cinema. I’m proud of that. Creating my own language. I live it on my own terms. I’m doing it on my own terms.

Parang there’s some contradiction in that given na ‘yon nga expansive, durational ‘yong films mo, but on the other side, you also feel na very limiting pa din ‘yong cinema.

Diaz: Yeah, you talk about duration, nililimitahan ang cinema. Parang institutionalize ‘yong you don’t go beyond three hours. You do fast grant. They’re also suspects ng cinema-milking na ‘wag mong wasakin ‘yong orthodoxy. If you get out of the orthodoxy, parang hindi na cinema sa kanila. You’ll get branded na pang-festival lang ‘yan. Comatose cinema ka lang. Of course, wala namang prejudice sa ibang sumusunod lang lagi sa convention. Pero sana palawakin natin. Let’s make it really free. Lawakan ang cinema na mas committed sa cultural perspective, hindi lang sa entertainment, hindi lang sa profit motive, hindi lang sa big stars.

And the problem with big festivals, even small festivals, nakakalimutan nila ang cinema sa ibang punto. You go to the festivals, ma-di-disappoint ka lang watching all these parties, all these decadence, hedonism, all these fiestas, and they forget cinema. Ano ba ang cinema? It’s sad to say that, but a lot of festivals are like that. Mas festival talaga. Fiesta. We forget about culture, we forget about pushing this medium towards committing to humanity’s betterment, or to understand the human condition more. So there’s the irony and contradictions lagi sa paggawa ng pelikula.

Just to build on that, is free cinema really possible under the conditions that we have right now?

Diaz: Yes, of course. Basta matutong maging malaya lang ang filmmaker, without the impositions of the big market and capitalist perspective. Sana mas sa sining at kultura. Hindi mo naman pwedeng ilahat e. Okay kung gusto mong kumita, gusto mong gumawa ng promotion, good, pero huwag naman lahat. Yeah, it’s possible.

And I want to go back to that — doing cinema alone again. When I started naman, mag-isa lang talaga ako, with a borrowed camera, and you create something na hindi mo in-e-expect na limang daan ‘yong manonood. Kahit si Mang Pedro lang ang makapanood, basta naunawaan niya, it’s great. For me, ‘yong simplicity ng perspective na ‘yon, siguro ‘yon ang cinema, kaysa ‘yong iniisip kong epic poem at saka nobela.

Kanina you mentioned your near-death experience nga after filming Magellan. Did it make you think to perhaps take a break muna and decompress?

Orencio: Definitely, he has to take a break until July. But like break na retiring, no way.

Diaz: Tingin ko marami pang gagawin. Ang daming ideas na lumalabas ‘pag nakahiga kami. Para siyang LSD trip na ang daming stories na lumalabas ‘pag malakas ‘yong gamot. Sa attitude ko sa buhay, it’s another life dahil muntik na ako [ng mamatay]. Na-re-energize ako to do more, and be more careful with health of course. It’s part of the struggle. I’m seeing things more na, you know, I don’t want to use the word “spiritual” pero mas may serenity na perspective. Accepting my mortality. Even sa paggawa, I realized that. Sinabi na ‘yan dati ni [Andrei] Tarkovsky. But ma-re-realize mo lang naman ‘yon ‘pag may tragedies, mishaps sa health mo, or nag-ma-mature ka na. Now that I’m 66, maybe it’s a different level ng paggawa, ng pagkukwento, ng paghahabi ng salita, or even a new approach sa cinema. Another language to be created maybe.

What do you think has changed in your philosophy as a filmmaker and storyteller over the course of your career, if at all?

Diaz: May mga kwento pang pwedeng ikwento. I seek serenity more now, pero mas malaki na ‘yong doubts ko sa medium. I find it really limiting now given what’s happening with cinema. So, ang sakin lang is, parang wala pa tayong nagagawa. I feel that wala pa akong nagagawa.