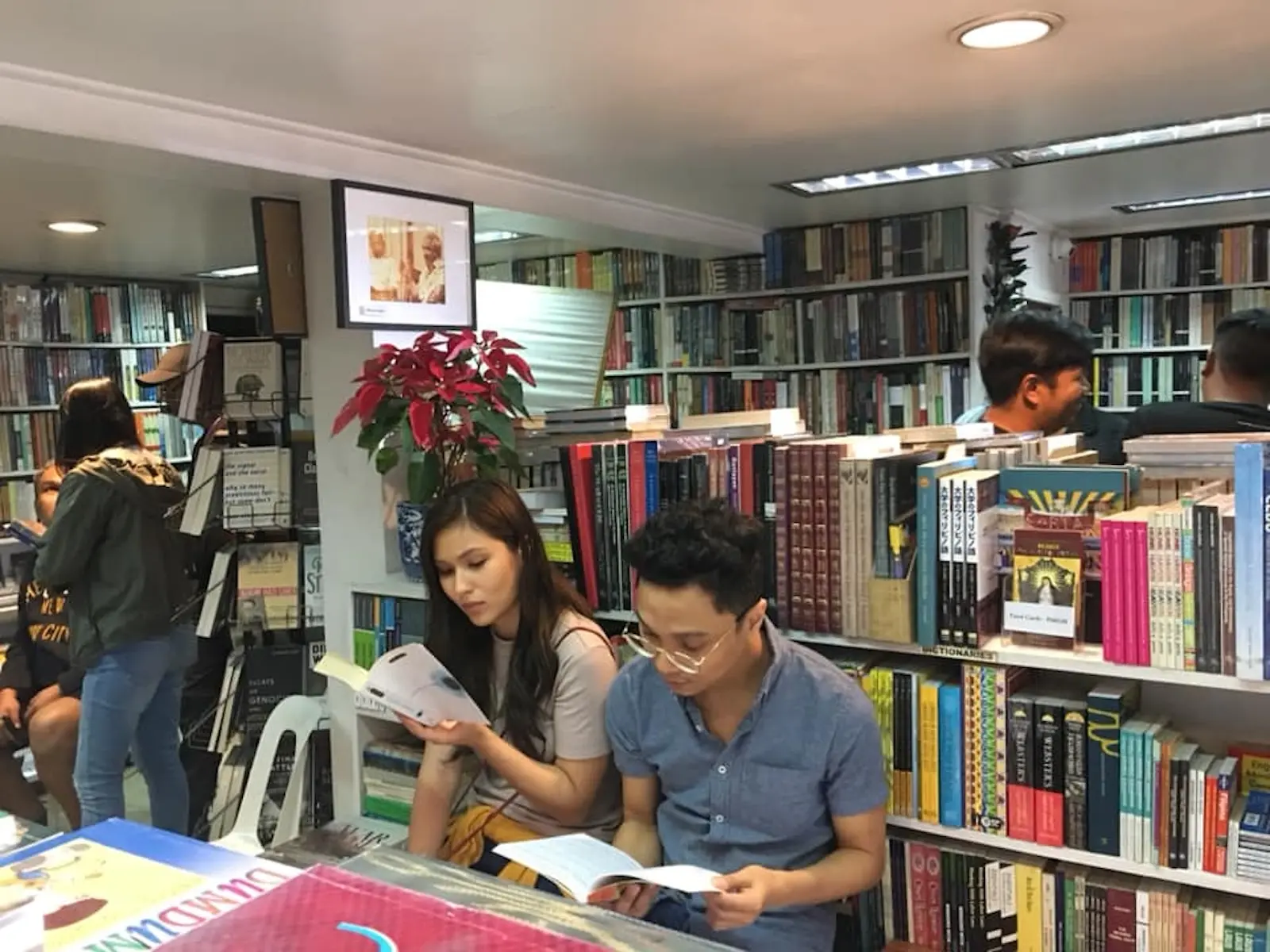

To many writers in Manila, Solidaridad Bookshop was synonymous with home.

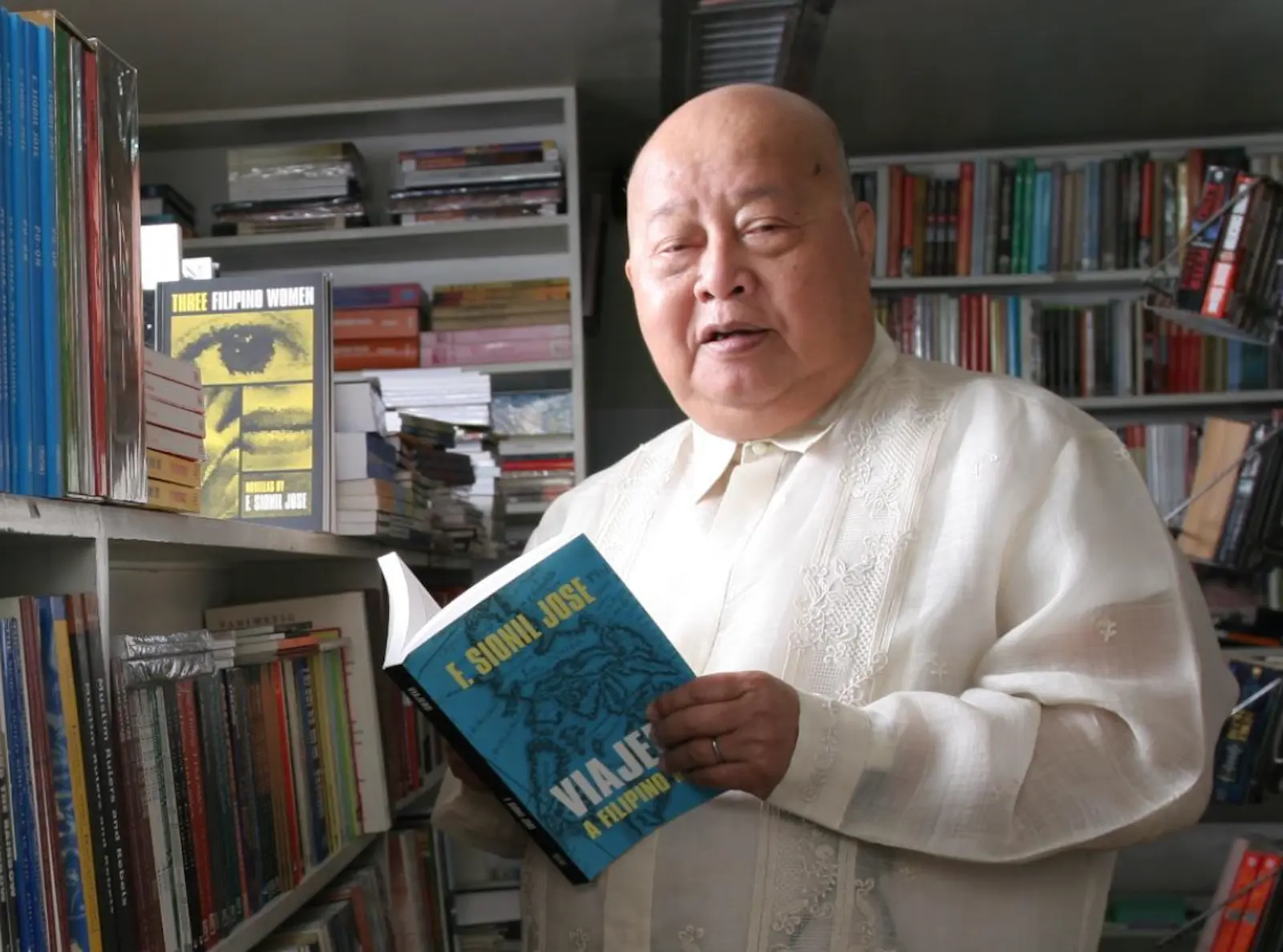

Established in 1965 by the late National Artist for Literature F. Sionil José, fondly known as “Manong Frankie” to peers and protégés, Solidaridad Bookshop quickly became more than just a place to buy books. With its distinctive red sign, shelves stocked with both contemporary Filipino bestsellers and rare literary finds, and upper rooms that once hosted some of the country’s most respected writers in spirited discussion, Solidaridad stands as a true literary landmark in Manila.

“I don’t know if we have spaces like [Solidaridad] that exist today,” writer Nash Tysmans told Rolling Stone Philippines. Tysmans, who has written for publications and news outlets such as Rogue Magazine, CNN Philippines Life, and the Philippine Daily Inquirer, spent much of her twenties at Solidaridad, growing closer to José (or “the old man,” as she affectionately called him) and his wife Tessie. “I have too many favorite memories of Solidaridad,” said Tysmans, “On the second floor, where they’d host big events, the old man also had his office, and sometimes the door would be closed. But there was this one event where we’d grown so fond of each other, the two of us just kept talking in his office.”

“That was quite special for me as a writer,” added Tysmans, “that he showed himself to the people who would come to visit him. Solidaridad was really an extension of himself.”

solidaridad: A Place to Congregate

José is best known as the acclaimed author behind towering works of fiction, such as the five-novel series The Rosales Saga (Po-on, Tree, My Brother, My Executioner, The Pretenders, and Mass), and is frequently touted as a Nobel Prize for Literature nominee. He was also a dedicated mentor to generations of younger writers, offering them guidance and a space where their voices could grow. In 1957, he founded the Philippine Center of International PEN (Poets, Essayists, and Novelists) and used Solidaridad as its headquarters, creating a haven where writers could form a community for themselves.

“Until the pandemic changed our lives, there were monthly PEN meetings at Solidaridad for the first two decades of the 21st century,” writer Menchu Aquino Sarmiento recalled in a Facebook post paying tribute to the bookstore. “I will always be grateful to [José], who encouraged me to write, and urged me to bring my two daughters to PEN meetings when he learned they were published writers too.”

Tysmans recalled how José’s mentorship gave her the confidence she needed to pursue her career as a writer. “I came to Solidaridad when I was just out of university and was unsure about what to do with my life,” she said. “But I remember after I wrote a story about the old man for Rogue, he was so happy with it that he sent me a pen and a note telling me he was flattered by what I’d written. It’s really those kinds of things, right? When you’re nobody in the industry and you’re still trying to understand your own voice, it was so important to have an established older writer tell me that I had important things to say.”

Tysmans’ connection to José and the bookshop he left behind is one shared by many writers, including Palanca Award-winning author Jose “Butch” Dalisay Jr. “Solidaridad and [José] were inseparably conjoined in the public’s imagination of a man who was not only our most productive and best-known novelist, but also an indefatigable purveyor of great literature and critical, if occasionally controversial, thinking,” Dalisay wrote in his column at The Philippine Star.

Although he and José formed a close friendship that lasted until the latter’s death in 2022, Dalisay, like others in the literary community, disagreed with José’s political views in later years regarding former President Rodrigo Duterte’s administration. “I did not share these views, and he knew that, but I think we had quietly decided that our friendship was more important than our politics,” wrote Dalisay.

Tysmans also acknowledged that the Duterte administration caused friction between her and José. “We didn’t always agree politically, but they were really like my family,” said Tysmans. “Even with all of that… the bookshop still meant so much to me. They always meant so much to me. It was really the only place that gave me the courage to explore different ideas and make room for dissent.”

An Uncertain Future

However, it’s difficult to say what the future holds for Solidaridad. On June 28, José’s eldest son, Antonio, officially announced in an interview with The Varsitarian that he would be putting the store up for sale. “After me, none of my siblings will be able to manage it,” he said. “We are all getting old. My siblings are all abroad, [and] it was only I who came back to take care of our parents and manage the bookshop. If I were a lot younger, I would not sell [it] at all.”

This news has led many to reflect on what Solidaridad has meant to them. “Solidaridad wasn’t just a bookshop,” wrote Arvin Malabanan, a longtime patron of the store, on Facebook. “It was a quiet refuge, a secret I shared with book lovers, bibliophiles, poets, essayists, novelists, writers, dreamers, and ghosts of history. Now, as Solidaridad Bookshop is about to be sold, I feel like I’m losing a piece of my soul. But I’ll carry its spirit, always and forever.”

“I really hope that the buyer embodies the same characteristics that the Josés had,” Tysmans said when asked about her hopes for the store’s future. “I hope they have a vision for it. These are big shoes to fill, and I wouldn’t know what to do in that position, because they’ll need to continue that legacy.”

“I wouldn’t want it to become a museum,” added Tysmans. “It needs to be alive.”