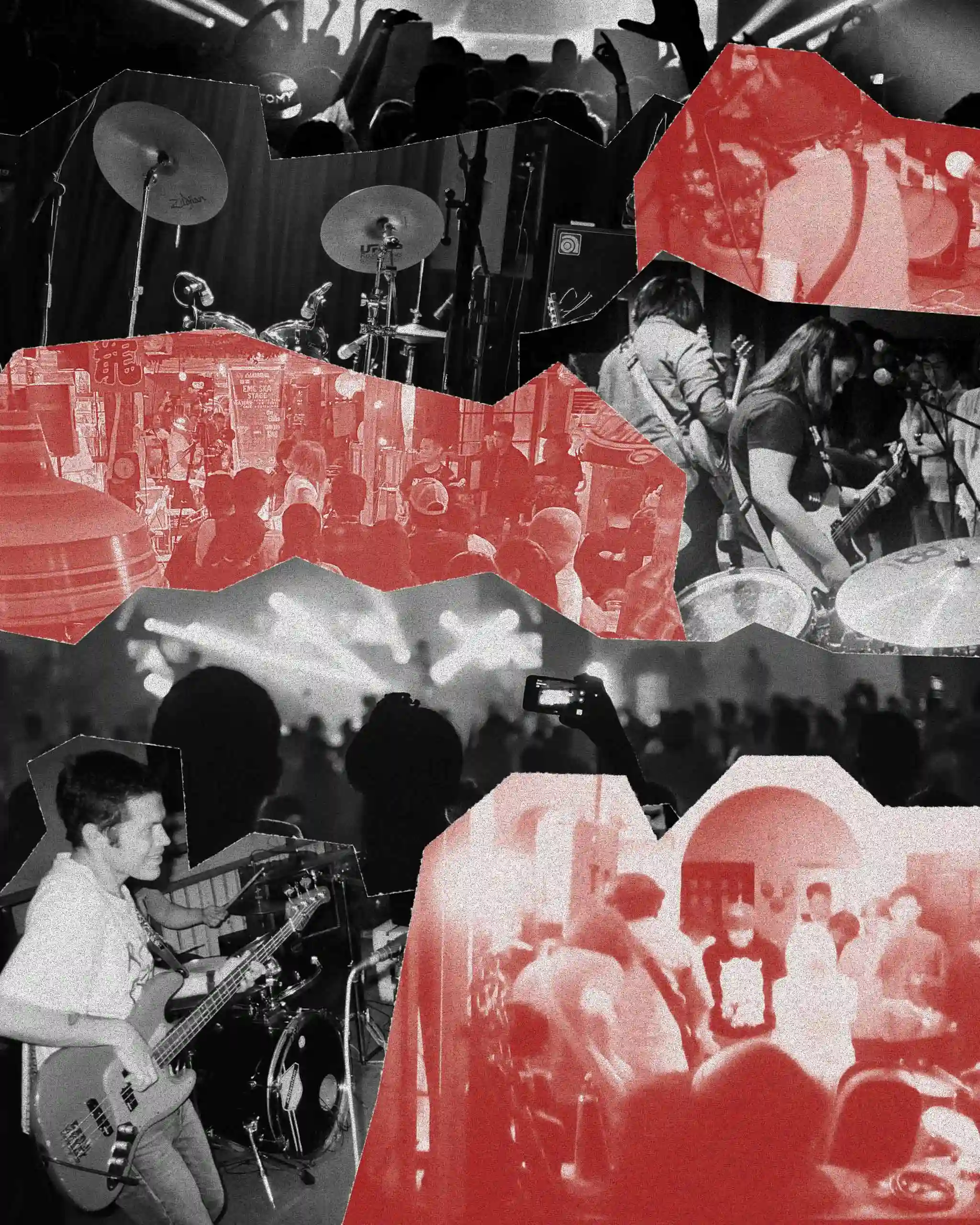

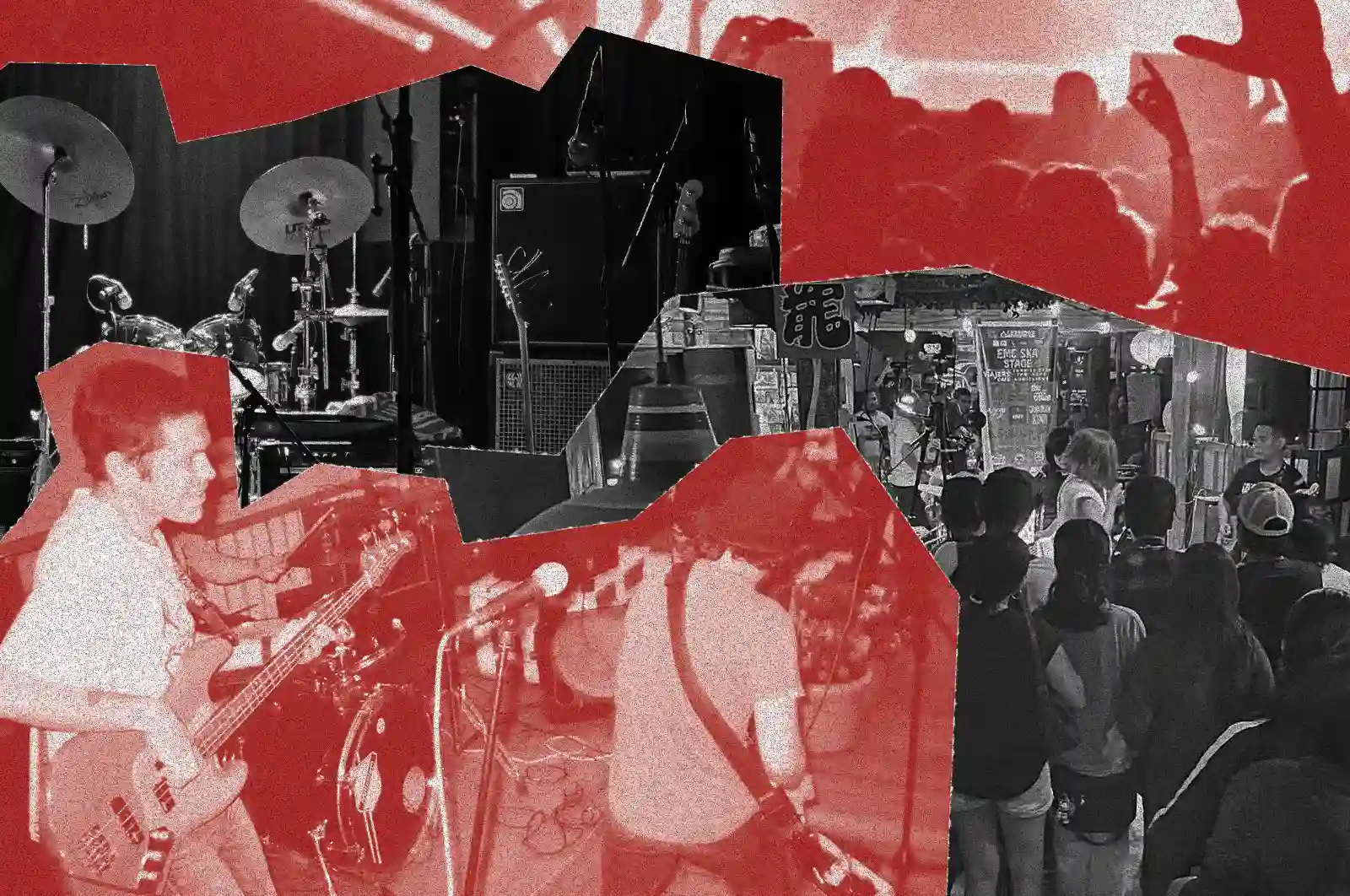

Live music venues in the Philippines are running out of time. Once held together by community labor, free spaces, and a sheer love for music, the country’s independent gig circuit continues to face rising rent costs and minimal cultural support. Venues like Mow’s in Quezon City, Sining Shelter in Parañaque City, and Viajero’s Café in Cagayan de Oro have become sanctuaries for musicians, yet staying open has become a monthly crisis.

In November 2024, the U.K. government urged the live music industry to introduce a voluntary ticket levy on stadium and arena concerts to support struggling grassroots music venues, festivals, artists, and promoters. The proposed levy would be industry-led and built into ticket prices, with revenue redistributed through a charitable trust. The aim is to direct a portion of profits from large-scale tours back into the venues and communities where many major acts got their start. This illustrates how public support for grassroots music venues is possible, and the Philippines — where accessible public spaces are few and far between — could benefit from a similar initiative. Venues, especially those that serve as homes for music and the arts, often fill this gap by providing space for community and creative expression.

President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, Jr. is set to deliver his fourth State of the Nation Address on July 28. While he’s expected to cover the country’s most pressing issues, cultural funding is rarely discussed. For the Philippines’ small venue operators, the wait for real support continues even as the stage lights dim around them. But despite this lack of public infrastructure, grassroots music venues insist their space is home to the next wave of Filipino talent. The question isn’t whether they’re profitable, but whether the music scene can survive without them.

Rolling Stone Philippines sits down with venue owners and independent production organizations on what it takes to keep a cultural space alive.

Tim Ng, 34, Marikina City

Tim Ng’s venue, Mow’s, runs with a mix of stubborn loyalty and realism. After more than a decade, the Quezon City bar, located in the basement of Kowloon House in Matalino Street, has become a rare constant in Metro Manila’s live gig scene. It does so by leaning in on the music, but also evolving with its patrons.

“We’re just lucky na we don’t have to pay rent… We’re able to sustain our prices,” Ng tells Rolling Stone Philippines. “But at the same time, we can’t really expand it much. I like being in this spot where we remain accessible to a lot of artists and productions.”

That philosophy helped Mow’s survive the pandemic. While many spaces shut down or pivoted into safer formats, Ng and his team persisted. They balanced finances, tweaked operations, and slowly reopened without compromising the space’s identity or what regulars expect from them. Ng knows that Mow’s isn’t immune to the churn of rent, trends, or city politics. But for now, it stands resilient against the rising price of beer, and the demands of marketing.

“I’d be lying if I didn’t say we also suffer from it,” he says about the cost of goods. “It affects everyone.” Ng also observes how each venue operates depending on how normalized a genre is within that space, with spaces like Saguijo in Makati and Jess & Pat’s in Maginhawa managing to stay afloat despite the challenges.

“You go into it because it’s your passion. You want to support artists. So, I think [the trouble is] really just economics at this point.”

Tonchi Mercado, 25, Parañaque City

Tonchi Mercado is the 25-year-old founder of the now-dormant DIY venue Sining Shelter, and vocalist for the international collective Fax Gang. For them, independent live music in Manila is hanging by a thread.

“A lot of venue closures are a symptom of a few things,” they tell Rolling Stone Philippines. “I think some of it has to do with the lack of government-backed culture funding. That’s not really something that’s given to grassroots venues here.” Mercado believes there aren’t many programs for aspiring business owners to take a chance on something like a music venue, which leads them to fall back on more lucrative brick-and-mortar businesses like food, beverage, and hospitality.

“I really want to see venues run by people who love music. Yung talagang mahal nila ‘yung ginagawa nila. A safe, open playground for musicians.”

Sining Shelter is actually Mercado’s family home, repurposed into a live music venue. As such, it doesn’t have the burden of rent; that gives it an edge, but not the immunity from economic strain. With no landlord to answer to, Sining Shelter held either free to minimal rent costs for booking community-driven shows with almost reckless abandon. “We’re just throwing shows for the heck of it, honestly. It’s a DIY, grassroots-type thing,” they say. “But now, we’re thinking long-term. Sustainability means making sure it’s generating value, no matter what time or day of the week. The space should be generating quote-unquote ‘value.’”

For Mercado, a mark of a good venue is not having it depend on its musical acts to draw a crowd; it should be a space that bridges performers and audiences under one communal space. “[People go] to that venue because there’s stuff playing at that venue… People care about it… It’s the venue that’s one of the primary selling points,” they say.

They note that while Metro Manila lacks experimental, mid-sized venues for new or outsider scenes to grow, they also hope that a focus away from Manila, paired with modest cultural funding, can support music venues operating at the fringes. Until then, misfits will have to keep building their own stages from scratch.

Jacques Palami, 37, Bacolod City

Jacques Palami of the music pop-up Now.here in Bacolod doesn’t see the collapse of venues across the country as a pandemic-era crisis. To him, it’s a systemic one, and the pandemic only exposed how fragile that system has always been.

For Palami, keeping music venues alive is a necessity. “[Music venues] rely on personal sacrifice, volunteer energy, and a lot of creative problem-solving,” he says. “But passion won’t pay rent, solve frequent brownouts, or secure permits. People have called it DIY, but often it’s just code for ‘no one else showed up.’”

Even when artists build spaces from the ground up, they still face gatekeeping. Palami points out that in cities like Tacloban, older cultural institutions often ignore or dismiss youth-led initiatives. “I’m 37,” he says, “and funnily, I’m still considered one of the ‘young movers’ here.”

But Now.here is a space dedicated to blurring genres, offering space for disciplines to collide. One edition saw DJ and producer YLMRN performing with a tribal dance troupe and players of indigenous instruments. “When a techno set blends with ritualistic movement, it opens a different emotional register, almost creating a new genre in itself,” Palami explains.

The business end, however, is brutal. Without sponsors or grants, it runs mostly on favors and community grit. “There’s no safety net, and that’s the problem,” he says. “We need to stop expecting organizers to carry the full financial burden of culture-making.”

When Palami tried to book a show for a Bohol-based band and couldn’t find a single willing venue in Tacloban, the message was clear: There still aren’t enough spaces that treat music as essential infrastructure. “When people feel like they have to move to a bigger city just to be heard, or even hear something different, then clearly the infrastructure isn’t [here] yet,” he says. “Having enough venues means having diversity [of] genres, crowds, [and] ways of organizing sound. I’d love to see more multi-purpose, community-driven spaces where young people can throw a rave one night, and a poetry show the next. Places that feel like a canvas.”

KC Salazar, 36, Cagayan De Oro City

According to KC Salazar — vocalist of dream pop outfit KRNA and co-organizer of Indie CDO — Cagayan De Oro only has one regular venue for original music: Viajero Café, a small hybrid space that wasn’t built with live music in mind. Most other venues, Salazar explains, prioritize mainstream or show band entertainment.

“[Other venues] are not really run by people who love music,” she says. “That’s why there’s no proper gear, and [most venues] rarely engage with the community.” To address this lack of infrastructure, Salazar has, over the years, steadily acquired amps and PA systems to make events possible, even in unorthodox spaces. “The more convenient and low-cost it is for venue owners, the more likely they’ll let us use their space,” she says. “We do all the work. They just give us the floor.”

Last April, Indie CDO transformed a function hall — typically reserved for weddings — and hosted a show for an Manila-based indie-folk band Munimuni, attended by over 200 people. “‘Yan rin ‘yong isang problema dito sa CDO. ‘Yong medium size na venue [na] kaya over 200 people, mahirap [hanapin],” she says, nothing that she also rallied friends to borrow equipment and set up shop in the venue to avoid sponsorship fatigue.

Salazar believes a music venue should be more than just a bar. “Parang siyang cultural hub, may diversity in sound. Tapos ‘yong audience, curious sila,” she says. “I really want to see venues run by people who love music, ‘yong talagang mahal nila ‘yong ginagawa nila. A safe, open playground for musicians.”